In the early tenth century there was a powerful Irish-Norse viking warlord called Óttar.[1] He was a jarl (or earl). He and his family contested with the descendants of King Ívarr ‘the Boneless’[2] – the co-founder of the most important and long-lasting Irish-Norse dynasty[3] – for the leadership of the Northmen of the diaspora after they had been temporarily expelled from Dublin by the Irish in 902. He spent time raiding in Brittany and then, rather less successfully, in England and Wales, before returning to Ireland where he established the town of Waterford.[4] Having had to accept the overlordship of Ívarr’s grandson Rögnvaldr, Óttar died fighting at Rögnvald’s [5] side against the Scots and English Northumbrians on the banks of the River Tyne in 918.[6] Here I will try to piece together Óttar’s story from the meagre sources we have. In so doing I think we can join together a few historical dots. This can tell us something of Norse Ireland and the fate of Northumbria, whilst also shedding some light on the very earliest Scandinavian settlements in the north-west of what is now England, i.e. Lancashire and Cumbria.

The dearth of records can be viewed purely as a gap in the tradition, brought about through a nadir in the writing of history, rather than due to an absence of events.[7]

When Walther Vogel, the great historian of the Northmen in France, wrote this in 1906 he was talking about events in the Frankish kingdoms in the first decade or so of the tenth century. But the same applies to the history of north-west England at the same time. It was during this period that the first viking bases appeared on the coasts of Cheshire, Lancashire and Cumbria. Over the coming decades these Scandinavians eventually spread out, stopped raiding, and settled down to farm and fish.

As F. W. Wainwright, perhaps the greatest historian of the Scandinavian arrival in north-west England, wrote:

As a mere episode the Norse immigration must be considered outstanding. But it was not a mere episode. It was an event of permanent historical importance.[8]

Óttar’s story can tell us just a little about the nature and timing of all this.

Óttar’s return to England

The twelfth-century chronicler John of Worcester tells that in 914:[9]

The Severn Estuary

The Pagan pirates, who nearly nineteen years before had crossed over to France, returned to England from the province called Lydwiccum (Brittany), under two chiefs:[10] Ochter and Hroald, and sailing round the coast of Wessex and Cornwall at length entered the mouth of the river Severn. Without any loss of time they fell upon the country of the Northern Britons[11], and carried off almost every thing they could find on the banks of the river. Having laid hands on Cymelgeac[12], a British bishop, on a plain called Yrcenefeld,[13] they dragged him, with no little joy, to their ships. King Edward redeemed him shortly afterwards for forty pounds of silver.

Before long, the whole army landed, and made for the plain before mentioned, in search of plunder; but the men of Hereford and Gloucester, with numerous bands from the neighbouring towns, suddenly fell on them, and a battle was fought in which Hroald,[14] one of the enemy’s chiefs, and the brother of Ochter, the other chief, and great part of the army were slain. The rest fled, and were driven by the Christians into an enclosure, where they were beset until they delivered hostages for their departure as quickly as possible from king Edward’s dominions.

The king, therefore, stationed detachments of his army in suitable positions on the south side of the Severn, from Cornwall to the mouth of the river Avon, to prevent the pirates from ravaging those districts. But leaving their ships on the shore, they prowled by night about the country, plundering it to the eastward of Weced (Watchet), and another time at a place called Porlock.[15] However, on both occasions, the king’s troops slew all of them except such as made a disgraceful retreat to their ships. The latter, dispirited by their defeat, took refuge in an island called Reoric (Flat Holm),[16] where they harboured till many of them perished from hunger, and, driven by necessity, the survivors sailed first to Deomed,[17] and afterward in the autumn to Ireland.

John of Worcester took his information from the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, all versions of which tell much the same story.[18]

Island of Flat Holm in the Britol Channel where Ottar’s vikings took temporary sanctuary

The days when vikings could raid with any success in Wessex were over. The West Saxon king, Edward the Elder,[19] who was by now king of Mercia as well, was well on the way to creating a unified and centralized England, although he and his son King Æthelstan still had more fighting to do before this end was achieved, especially in the north. But our concern here is with the Norse jarl Óttar.

View of sea from Landevennec Abbey in Brittany

We know a little about what Óttar’s vikings were doing in Brittany immediately prior to their appearance in the Severn from Breton and French sources. Northmen had been actively raiding and occasionally trying to settle along the coasts of France, Brittany and Aquitaine during the previous century. But in the late ninth century Alan the Great, the duke of Brittany, had inflicted several reverses on the vikings, after which until his death in 907 we are told that the ‘Northmen hadn’t even dared to look towards Brittany from afar’.[20] But following Alan’s death factional strife broke out and Brittany was weakened. The Northmen ‘stirred themselves again and in front of their face the ground trembled’.[21] In the ‘Chronicle of Nantes’ during the episcopate of Bishop Adelard (i.e. after 912) we read that the rage of the Northmen began to re-erupt as never before.[22] One viking target was the Breton monastery of Landevennec. In one of the abbey’s computes we find a two line note in the margin next to the year 914, it reads: ‘In this year the Northmen destroyed the monastery of Landevennec’.[23] These Northmen were probably those of Óttar and Haraldr.

Who was Óttar?

Before turning to look at what became of Óttar in Ireland, who was he and where had he originally come from? There is little doubt that jarl Óttar was Irish-Norse; that is he was a powerful leader of the Northmen who had come to Dublin in the 850s – called the ‘dark foreigners’ by the Irish – who subsequently went on to create the Scandinavian kingdom of York after 866. Some historians have equated him with a certain Ottir mac Iargni (i.e. Óttar son of Iarnkné),[24] who had killed ‘a son of Ásl’ in Ireland in 883.[25] Asl was one of the brothers of Ívarr I and Óláfr, the co-founders of the Danish Dublin dynasty in the 850s.[26] Óttar was in league with Muirgel, a daughter of the Irish king Mael Sechlainn, who was one of Ívarr’s bitterest enemies. As Clare Downham suggests in ‘Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland – The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014’:

Óttar’s family may have briefly come to the fore as rivals of the sons of Ívarr due to the weakness of Sigfrøðr who was killed by a kinsman in 888.’[27]

This Óttar’s father was probably the Iarnkné who had been beheaded in 852 after being on the losing side of a battle in Ireland between two opposing viking groups.[28] This would mean that Óttar would have been at the very least thirty years of age in 883, and quite likely even older. When we find a jarl called Óttar in the Severn estuary in 914, if he were the same man he’d have been over sixty or yet older still. While possible, I don’t find this at all credible, particularly because, as we will see, the Óttar on the Severn in 914 went on to be one of the main Norse leaders in important events and battles in Ireland and England up until his death in 918. Viking warlords leading their troops into battle were never seventy years old! It is more likely that ‘our’ Óttar was perhaps either a son or nephew of Óttar son of Iarnkné.

Viking Dublin

The idea that Óttar came from a family of Dublin-based viking leaders who had from time to time tried to challenge the rule of Ívarr’s sons and grandsons, gains more support from an entry in the generally reliable ‘Annals of Ulster’. Under the year 914 it reads:

A naval battle at Manu (the Isle of Man) between Barid son of Oitir and Ragnall grandson of Ímar, in which Barid and almost all his army were destroyed.[29]

Ragnall is the Gaelic name for Rögnvaldr, who was a grandson of Ívarr ‘the Boneless’. Here, as elsewhere, Ívarr is named Ímar in Irish sources; while Barid is Norse Bárðr. Was this naval fight part of an attempt by Rögnvaldr and his brother or cousin Sigtryggr to assert or reassert their supreme leadership of the Dublin Norse of the diaspora? It looks that way.

Viking Dublin

As I have mentioned, in 902 the Northmen had been expelled from Dublin, their king at the time was probably Ívarr’s grandson Ívarr.

The heathens were driven from Ireland, that is from the longphort of Ath Cliath (Dublin), by Mael Finnia son of Flannacan with the men of Brega and by Cerball son of Muirecan with the Leinster men… and they abandoned a good number of their ships, and escaped half dead after they had been wounded and broken.[30]

Perhaps Óttar had been one of the ‘heathens’ who ‘half dead’ had desperately fled for their lives? I believe it quite likely.

Maybe Óttar had fled with Óttar son of Iarnkné – who might conceivably have been his father? I’ll leave this conjecture aside for the moment, but will return to it later.

Different groups of exiled Scandinavians went to the Wirral, to Lancashire, to Scotland, probably to Cumbria, and to France. Ívarr grandson of Ívarr was killed by the Scots in Pictland in 904:

Ímar grandson of Ímar, was slain by the men of Fortriu, and there was a great slaughter about him.[31]

King Alfred the Great fights the Vikings

The story told by John of Worcester I started with said that ‘the Pagan pirates, who nearly nineteen years before had crossed over to France, returned to England from… Brittany’. What does John of Worcester mean by this? Is he saying that Óttar and his warband moved from England in around 896? Or does the comment refer to events after the expulsion of the Norse from Dublin in 902? In fact I think that it refers to neither. I believe John of Worcester’s comment is not specifically concerned with Óttar’s vikings, but rather refers to the year 896, when a small remnant of an army of vikings, which had come back to England 893 after fourteen years ravaging the coasts of France and Brittany, were finally defeated by Alfred the Great after nearly four years fighting and went back to the kingdom of the Franks, where some of them would soon establish the dukedom of Normandy in 912.[32] Thus 896 was the last time the kingdom of Wessex had been troubled by vikings – nineteen years before Óttar appeared on the River Severn.[33]

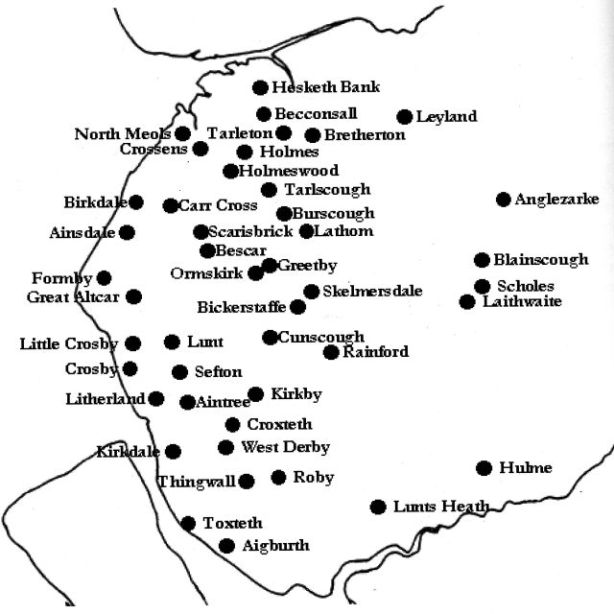

In the years between 902 and 914 there are only a few of mentions of the Dublin Norse exiles. Most extensively there is the story of Ingimundr, whose people settled on the Wirral and tried (in league with others of the diaspora) to take Chester from the Mercians in about 910.[34] There is also the death of Ívarr grandson of Ívarr in 904 in ‘Pictland’ referred to earlier.

Ímar grandson of Ímar, was slain by the men of Fortriu and there was a great slaughter of them.[35]

We also find various named Scandinavians being killed by the English West Saxons and Mercians at the Battle of Tettenhall in 910 – including confusingly a jarl called Óttar. The English

slew many thousands of them; and there was king Eowils slain and king Halfdan, and Ottar jarl, and Skurfa jarl, and Othulf hold[36], and Benesing hold, and Olaf the Black, and Thurferth hold, and Osferth Hlytte, and Guthferth hold, and Agmund hold, and Guthferth.[37]

Viking York

These Scandinavians were the Danes of Northumbrian York. They were on their way home from raiding deep into English territory when they were caught and beaten by King Edward’s army in Staffordshire.[38] Yet I think there is room to believe that at least a few in this Scandinavian army must have been from the Irish-Norse coastal bases in north-west Britain.[39] The Yorkshire/Northumbrian ‘Danes’ were relatives of those expelled from Dublin. For example, King Hálfdan, who was killed at Tettenhall, was descended from an earlier chieftain called Hálfdan who had started the Scandinavian settlement of Yorkshire following his capture of York in 866, and who was also likely the brother of the co-founders of the Dublin Norse dynasty: Ívarr and Óláfr.[40] We don’t know who the jarl Óttar killed at Tettenhall was. The name is common enough, but the fact that he was a jarl and was named in the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’ immediately after King Hálfdan and King Eowils shows he was an important man. He could well have been a jarl of York who was not in any way connected with the jarl Óttar who came back from Brittany in 914, but given his name and position he just might have been related. Perhaps he could even have been one of the vikings expelled from Dublin in 902 who had landed on the coast of north-west Britain and made his way to York to seek help or refuge with his York cousins?[41] Most historians suggest that one of the main objectives of the expelled vikings would have been to do just this, and that the huge silver-hoard found in 1840 at Cuerdale on the Ribble estuary in Lancashire, which is conventionally dated to around 905.[42] might be the war-chest of a viking leader collected both from raiding and from the Danes of York to finance an attempt to retake Dublin.[43]

The whole question of other Óttars is made even more difficult because we hear of another Óttar in the ‘Fragmentary Annals of Ireland’. In the part in which Óttar is mentioned the compiler is telling the story of Ingimund’s coming from Dublin to the Wirral and later attacking Chester, events dated between 904 and 910. He then tells:

Almost at the same time the men of Foirtriu[44] and the Norwegians fought a battle…. The men of Alba fought this battle steadfastly… this battle was fought hard and fiercely; the men of Alba won victory and triumph, and many of the Norwegians were killed after their defeat, and their king was killed there, namely Oittir son of Iarngna. For a long time after that neither the Danes nor the Norwegians attacked them, and they enjoyed peace and tranquillity… [45]

King Edward the Elder

So here we find an Óttar son of Iarnkné (here styled king) being killed in a battle against the men of Alba (the Scots). I mentioned earlier that Óttar son of Iarnkné might well have been the father of the Óttar who was defeated and driven off by the English in 914. Was the ‘king’ Óttar son of Iarnkné reputedly killed by the Albans sometime around 910 a different person to the jarl Óttar killed by the English at Tettenhall in 910? Or were they one and the same? We will never know, although the coincidence is worthy of note.[46]

There is also the intriguing thought proposed by Sir Henry Howorth in 1911 and supported by F. W. Wainwright[47] that the death of Óttar son of Iarnkné mentioned in the ‘Fragmentary Annals’ actually referred to jarl Óttar who, as will be discussed below, died fighting the Scots and Northumbrian English at the Battle of Corbridge in 918. On the whole I tend to think that this interpolated story in the ‘Fragmentary Annals’ is probably highly confused, mixing up different Óttars and different battles – a thing that is quite easy to do – so I’ll not place much reliance on it here.[48]

One final thought regarding Óttar and his family might be added. We know the names of some of Ívarr I’s sons: Bárðr who was Ívarr’s successor as King of Dublin after Ívarr’s death in 873 and died in 881; Sigfrøðr who then ruled Dublin until he was killed by a ‘kinsman’ in 888; and Sigtryggr who ruled till killed by other vikings in 893.[49] Does not the fact that one of Ívarr’s sons was called Bárðr coupled with the fact that a Bárðr son of Óttar was killed in a naval engagement off the Isle of Man in 914 suggest that sometime in the early history of the these Dublin vikings Óttar’s family and Ívarr’s family were related?

Óttar comes to Waterford

Here I think we can return to our story.

We left jarl Óttar departing the area of the Severn estuary in 914 and making his way, with the survivors of his defeat at the hands of the English, via South Wales to Ireland. His destination was the harbour of Waterford. The ‘Annals of Ulster’ tell us that in 914:

A great new fleet of the heathens on Loch dá Caech.[50]

Waterford Harbour

Loch dá Caech is the Gaelic name for Waterford harbour or bay. Waterford town had yet to be founded; in fact it was Óttar’s arrival that led to the creation of Waterford.[51] This notice comes immediately after the entry mentioned before which reads:

A naval battle at Manu between Barid son of Oitir and Ragnall grandson of Ímar, in which Barid and almost all his army were destroyed.[52]

‘Basilica’ of Tours on the Loire

This report is of great interest because it tells of a Bárðr, who was a son of an Óttar, being killed by Rögnvaldr in 914. It is most likely that this Bárðr was the same viking leader who was in league with another leader called Erikr and who had attacked the important town of Tours on the River Loire in 903.[53] In addition, most historians think that Bárðr and Erikr’s fleet in the Loire was most likely a contingent of the Dublin Norse expelled the year before. If all this is the case, then it suggests that Óttar and Bárðr could have been brothers and not father and son – both possibly being sons of Óttar son of Iarnkné. They had both spent time raiding in France and Brittany after 902, before returning to Britain in 914 when Bárðr was killed by Rögnvaldr while Óttar arrived on the River Severn.

As mentioned above, after Óttar had left England he and his fleet sailed via South Wales and then on to Waterford Harbour. Over the next twelve months more vikings arrived to join him at Waterford. The ‘Annals of Ulster’ for 915 continue:

A great and frequent increase in the number of heathens arriving at Loch dá Chaech, and the laity and clergy of Mumu[54] were plundered by them.[55]

In 916 ‘the foreigners of Loch dá Chaech continued to harry Mumu and Laigin’.[56]

What is clearly happening here is that Óttar’s returning forces are trying to re-establish themselves in Ireland, but they don’t yet feel strong enough to attack Dublin, held by the Irish since 902.

Ottar’s rival Rögnvaldr

But jarl Óttar was not the only viking leader wanting to return to Ireland. The other main force in the Irish Sea at the time was led by Rögnvaldr and his brother or cousin Sigtryggr, both the ‘grandsons of Ívarr’. As we have seen, Rögnvaldr had defeated and killed Bárðr son of Óttar in a naval engagement off the Isle of Man in 914, and I have already suggested that Óttar and Bárðr might have been brothers. The next we hear of Rögnvaldr is in 917, three years after Óttar’s arrival in Waterford:

Sitriuc, grandson of Ímar, landed with his fleet at Cenn Fuait on the coast of Laigin. Ragnall, grandson of Ímar, with his second fleet moved against the foreigners of Loch dá Chaech. A slaughter of the foreigners at Neimlid in Muma. The Eóganacht and the Ciarraige made another slaughter.[57]

Ívarr’s grandson Rögnvaldr came to Waterford with his fleet with the express intention of challenging Óttar’s viking force now established there. His brother, or cousin, Sigtryggr had landed at Cenn Fuait.[58] We don’t know exactly what transpired when Rögnvaldr ‘came against’ Óttar at Waterford, but I think we can imply from later events that Óttar had accepted or reaccepted Rögnvald’s supreme leadership of the Dublin Norse exiles operating in and around the Irish Sea at this time.

Under 917 the ‘Annals of Ulster’ report:

Irish and Norse fight

Niall son of Aed, king of Ireland, led an army of the southern and northern Uí Néill to Munster to make war on the heathens. He halted on the 22nd day of the month of August at Topar Glethrach in Mag Feimin. The heathens had come into the district on the same day. The Irish attacked them between the hour of tierce and midday and they fought until eventide, and about a hundred men, the majority foreigners, fell between them. Reinforcements came from the camp of the foreigners to aid their fellows. The Irish turned back to their camp in face of the last reinforcement, i.e. Ragnall, king of the dark foreigners, accompanied by a large force of foreigners. Niall son of Aed proceeded with a small number against the heathens, so that God prevented a great slaughter of the others through him. After that Niall remained twenty nights encamped against the heathens. He sent word to the Laigin that they should lay siege to the encampment from a distance. They were routed by Sitriuc grandson of Ímar in the battle of Cenn Fuait, where five hundred, or somewhat more, fell. And there fell too Ugaire son of Ailill, king of Laigin, Mael Mórda son of Muirecán, king of eastern Life, Mael Maedóc son of Diarmait, a scholar and bishop of Laigin, Ugrán son of Cennéitig, king of Laíges, and other leaders and nobles.[59]

The ‘Wars of the Gaedhil with the Gael’ reported that:

The whole of Mumhain (Munster) became filled with ships, and boats, and fleets, so that there was not a harbour, nor a landing port, nor a Dun, noir a fortress, nor a fastness, in all Mumhain, without fleets of Danes and pirates.[60]

These various battles fought in 917 against the Irish by the ‘dark foreigners’ of Rögnvaldr and Sigtryggr, with jarl Óttar’s forces now most probably forming a part of the viking army, were fought to re-establish their presence in Ireland and to try to retake Dublin. The Irish wanted to prevent this happening. The Battle of Cenn Fuait referred to in the annals (now called the Battle of Confey), which the vikings won, opened the road to retake Dublin and Sigtryggr recaptured the town in the same year:

Sitriuc grandson of Ímar entered Áth Cliath (i.e. Dublin).[61]

The ‘Wars of the Gaedhil with the Gael’ describes the taking of Dublin thus:

There came after that the immense royal fleet of Sitriuc and the family of Ímar, i.e. Sitriuc the Blind, the grandson of Ímar; and they forced a landing at Dublin of Áth Cliath, and made an encampment there.[62]

The Northmen were back as masters of Dublin after an exile of about fifteen years. They would remain contested masters there into the twelfth century.

Where had Rögnvaldr and Sigtryggr been?

Following the expulsion of 902, Óttar had been raiding in Brittany, and maybe in areas of the Frankish lands too, although for how long is not clear. But what of Ívarr’s two grandsons, Rögnvaldr and Sigtryggr? Where were they in the years between the expulsion from Dublin and their return to Ireland in 917?

An Irish-Norse King

As I have previously mentioned, another grandson of the first Ívarr was also called Ívarr. He was most probably the leader of the Irish-Norse when they were kicked out of Dublin in 902.[63] In 904, the same time that fellow exile Ingimundr was first settling on the Wirral near Chester, this Ívarr was killed by the Scots in ‘the land of the Picts’, while either raiding or trying to establish a base there. At the time of Ívarr’s death in 904, Rögnvaldr was probably a young man and Sigtryggr possibly still a boy.[64] So the question arises: Where were the bases of the fleets and warbands of the ‘grandsons of Ívarr’ before the naval battle in 914 and their return to Ireland in 917?[65] Although the annals and chronicles are silent on the matter, all the circumstantial evidence suggests that their base or bases were probably along the coasts of Lancashire and Cumbria. Most probably there was one on the River Ribble in Lancashire where an immense viking silver-hoard was found at Cuerdale in 1840 which is conventionally dated to around 905-910. Another may have been further north around Morecambe Bay or in the area of the later heavily Norse area of Armounderness in Lancashire.[66] It’s even possible that at this early date some vikings already had a base somewhere on the banks of the Solway Firth – the present border between Cumberland and Scotland.

Alex Woolf says:

The heathen refugees from Ireland seem to have settled along the eastern shores of the Irish sea.[67]

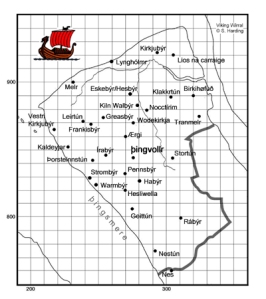

Scandinavian Wirral

One of the clearest indications that the refugees from Dublin had already made other bases along the coast and not just on the Wirral comes from the ‘Fragmentary Annals of Ireland’. Having told of Ingimund’s arrival on the Wirral in 903/4, it continues:

Ingimund came then to the chieftains of the Norwegians and Danes; he was complaining bitterly before them, and said that they were not well off unless they had good lands, and that they all ought to go and seize Chester and possess it with its wealth and lands. From that there resulted many great battles and wars. What he said was, ‘Let us entreat and implore them ourselves first, and if we do not get them good lands willingly like that, let us fight for them by force.’ All the chieftains of the Norwegians and Danes consented to that.[68]

So Ingimund brought together other ‘chieftains of the Norwegians and Danes’ for his plan to seize Chester. These other chieftains must have been in large part other groups of Dublin exiles based along the coasts north of the Wirral. When ‘Ingimund returned home after that’ he arranged for the viking ‘host’ to follow him.

Given that Rögnvaldr fought a naval engagement off the Isle of Man in 914 before he returned to Ireland, it might also be suggested (as it has been) that the ‘grandsons of Ívarr’ had a fortified base there too.[69]

First Scandinavian bases in Lancashire and Cumbria

What I am suggesting here is not just that the earliest Scandinavian bases along the coasts of north-west ‘England’ were established by the Dublin exiles in the early years of the tenth century, which is pretty much accepted by all historians, but also that in all likelihood many of these early bases and embryonic settlements were founded by the forces of ‘the grandsons of Ívarr’: Rögnvaldr and Sigtryggr.

Heversham, Westmorland

From these first bases the vikings continued their habitual habits and raided the lands of the western Northumbrian English. In this very obscure period we can catch glimpses of some of the raids they made and their consequences. The Historia de Sancto Cuthberto tells of a powerful English thegn in western Northumbria called Alfred son of Brihtwulf ‘fleeing from pirates’. He ‘came over the mountains in the west and sought the mercy of St Cuthbert and bishop Cutheard so that they might present him with some lands’. In the same source we also hear that Abbot Tilred of Heversham (in Westmorland) came to St Cuthbert’s land and purchased the abbacy of Norham on Tweed during the episcopate of Cutheard.[70] In all likelihood Tilred was fleeing from the Vikings too.

We can probably date these flights to between the expulsion of the vikings from Dublin in 902 and the death of Bishop Cutheard in 915. I prefer later in this period.[71] If these events were not caused by ‘the grandsons of Ívarr’ then who else was precipitating these Northumbrians to flee?

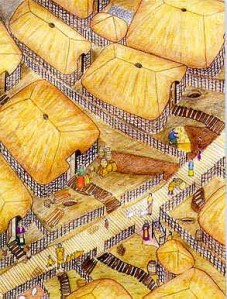

These early Norse bases and embryonic settlements along the north-west coast of what is now England were essentially defensive land bases for the viking fleets. No doubt some of the Norse farmed a little too, but the very extensive Scandinavian settlement of western Lancashire and much of Cumbria was a long drawn-out process that probably only really got underway after 920/930 and took many decades, indeed probably more than a hundred years, to complete.[72]

What the great historian Walther Vogel wrote about the vikings in the western and eastern Frankish kingdoms in the early years of the tenth century is most likely also true of the situation in north-west England in the same period:

The ‘army’ as such still existed… the warriors had not yet dissolved their warband and divided up the land to settle down to farm as individual colonists…

They probably obtained the necessities of life from small plundering raids in the surrounding area; they also certainly received tribute from the remaining… farmers in the countryside; finally with the help of their serfs and their slaves captured in war, they may have grown a few crops and kept a few cows. That this intermediate situation was enough for them; that the conquered land remained for so long undivided, can only be explained because the threat of Frankish attacks didn’t yet permit dissolution of the army.[73]

For the early Norse in Lancashire and Cumbria I believe the same would have been true. Not until the possibility of being completely annihilated and driven back into the sea by the English – whether Northumbrian, Mercian or West Saxon – or by the British (the Cumbrians/Strathclyde Britons) had receded, would the Norse risk dividing the land, spreading out and settling as individual colonists throughout much of Cumbria and Lancashire, as they eventually assuredly did.[74] And this dispersal, in my view, would not start in earnest for quite a number of years after the Battle of Corbridge in 918.

If all the forgoing is correct, then what we are catching a glimpse of in the records is that once Óttar returned to Ireland in 914 Ivarr’s descendants, who were most probably based along the coasts of Lancashire and Cumbria (and possibly also in the Isle of Man), decided that they too should return to Ireland. Here they soon managed to reassert their family’s former authority over Óttar and his men based at Waterford, before, after several fights with the Irish, recapturing Dublin in 917.

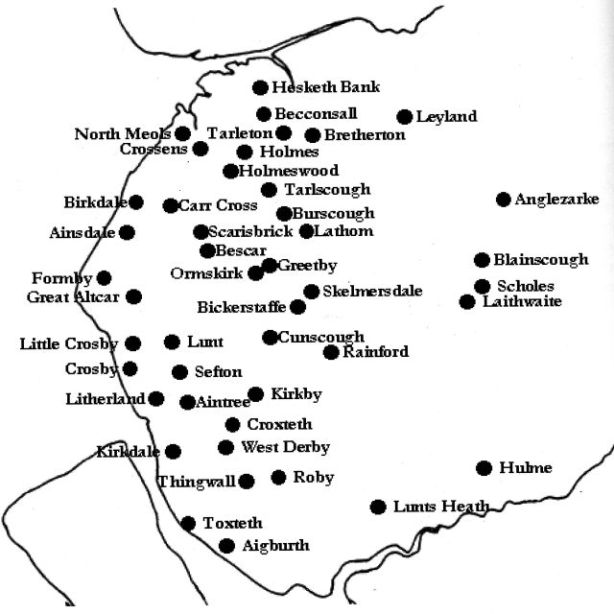

Scandinavian Lancashire

Óttar goes with Rögnvaldr to Northumbria

Let us now continue with Óttar’s story as best we can. Once the vikings were back in Dublin, Sigtryggr was left in charge there. His brother or cousin Rögnvaldr, together with jarl Óttar, decided to leave Waterford and return to Britain, where in the next year (918) they fought an important battle with the Scots of Alba and the Northumbrian English on the banks of the River Tyne: the Battle of Corbridge. Several English and Irish sources tell us something of what happened. The fullest account is given in the ‘Annals of Ulster’:

The foreigners of Loch dá Chaech, i.e. Ragnall, king of the dark foreigners, and the two jarls, Oitir and Gragabai,[75] forsook Ireland and proceeded afterwards against the men of Scotland. The men of Scotland, moreover, moved against them and they met on the bank of the Tyne in northern Saxonland. The heathens formed themselves into four battalions: a battalion with Gothfrith grandson of Ímar, a battalion with the two jarls, and a battalion with the young lords. There was also a battalion in ambush with Ragnall, which the men of Scotland did not see. The Scotsmen routed the three battalions which they saw, and made a very great slaughter of the heathens, including Oitir and Gragabai. Ragnall, however, then attacked in the rear of the Scotsmen, and made a slaughter of them, although none of their kings or earls was cut off. Nightfall caused the battle to be broken off.[76]

Vikings come ashore

The Historia de Sancto Cuthberto provides some of the background to the battle.[77] Having told of the flight of the English Northumbrian thegn Alfred son of Brihtwulf fleeing a Viking raid, which was discussed earlier and can be dated to the years prior to 915, the Historia then says that Alfred was given land by the Northumbrian Bishop Cutheard in return for services, and that:

These he performed faithfully until king Raegnald (Rögnvaldr) came with a great multitude of ships and occupied the territory of Ealdred son of Eadwulf, who was a friend of King Edward, just as his father Eadwulf had been a favourite of King Alfred. Ealdred, having been driven off, went therefore to Scotia, seeking aid from king Constantin, and brought him into battle against Raegnald at Corbridge. In this battle, I know not what sin being the cause, the pagan king vanquished Constantin, routed the Scots, put Elfred the faithful man of St Cuthbert to flight and killed all the English nobles save Ealdred and his brother Uhtred.

‘The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba’ says that the ‘battle of Tinemore’ happened in 918, and that King Constantin fought Ragnall, but adds that ‘the Scotti had the victory’.[78] However the general view is that the Battle of Corbridge was indecisive. Whichever side could rightfully claim the victory, and both did, as Alex Woolf says

The immediate result of the battle was that Ragnall, who had previously dominated the western regions of Northumbria since at least 914, became undisputed leader in the east also.[79]

Viking York

I won’t delve further here into the Battle of Corbridge, it has been, and remains, a subject of academic debate – for example was there one or more battles?[80] I would just like to make three points. First, jarl Óttar, who was by now a staunch supporter or at least a subordinate of King Rögnvaldr, is said to have died fighting the Scots and the English at Corbridge in 918. This brings to an end the very interesting Viking life. Second, after Corbridge the ‘Historia Regum Anglorum’ tells us that Rögnvaldr soon reconquered York.[81] Lastly, we might ask the question: Where had the Vikings’ ‘great multitude of ships’ landed before they defeated the Scots and the Northumbrian English at Corbridge? It could be that they left Waterford and sailed all the way round the north of Britain and then landed either near the Tyne or possibly even in the River Humber. However I believe it more probable that Rögnvald’s fleet first landed at one of their bases on the north-west coast of England and from there used one of the established direct routes across to Pennines to reach eastern Northumbria.[82] Clare Downham writes:

The location of Corbridge can reveal something of the circumstances of the motives behind the battle. Corbridge is located by a crossing point of the River Tyne. The site also had strategic significance as a fort near to Hadrian’s Wall. It presided over the ‘Stanegate’ a Roman road which ran west to east across Britain, and the road which ran north to south from Inveresk on the Firth of Forth to York. Rögnvaldr and his troops may have travelled overland from the Solway Firth or used the Clyde-Forth route across Alba to reach Northumbria. It may be supposed that they were planning to reach York but they found themselves being intercepted and confronted by enemy-forces.[83]

Given that the undoubted aim of Rögnvald’s army was to recapture York from the Northumbrians, I think it unlikely that it would have ventured to take the more northerly route through hostile Scottish territory. The more southerly ‘Stanegate’ is more likely, or even the quicker west-east route over the Pennines starting from the River Ribble in Lancashire. We’ll probably never know for sure.[84]

Eric Bloodaxe

Following the collapse of Northumbrian English power, the West Saxon English under King Æthelstan and his successors were set to take control of present-day Yorkshire, Durham and Northumberland. The last Norse king of York was Eric ‘Bloodaxe’, who was treacherously killed by a fellow Northman in 954 at Stainmore in Cumberland while fleeing from York across the Pennines – he was probably trying to find safety with his Norse brethren on the west coast or in Ireland.

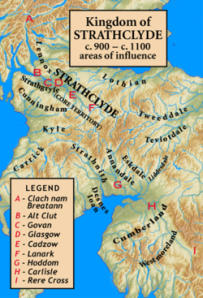

In what is now Cumberland, the Strathclyde Britons (referred to in English sources at the Cumbrians – hence the English term Cumberland) used the opportunity of the decline of Northumbria and the incursions of the Irish-Norse to try to re-establish some sort or rule south of the Solway Firth – which they seem to have done to some extent.[85] But that’s another story.

What became of King Rögnvaldr?

What became of King Rögnvaldr, the conquering descendant of Ívarr the Boneless? Although after the Battle of Corbridge he had been successful in gaining control of York, he was not immune to the raising power of the English under King Edward the Elder. In 919 and 920, King Edward built new fortresses at Thelwall and Manchester on the River Mersey and at Nottingham, thus ‘blocking off the approach over the moors from the southern portion of Northumbria around modern Sheffield’.[86] Edward forced a submission of his enemies, possibly at Bakewell. The ‘A’ manuscript of the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’ reported this event in 920:

And then the king of the Scottas and all the people of the Scottas and Raegnald, and the sons of Eadwulf, and all who live in Northumbria, both English and Danish and Northmen and others, and also the king of the Strathclyde welsh and all the Strathclyde welsh, chose him (Edward) as father and lord.[87]

And then under the year 921 the ‘Annals of Ulster’ report the death of Ragnall h. Imair ri Finngall 7 Dubgall, i.e. of ‘Ragnall grandson of Ímar, king of the fair foreigners and the dark foreigners’.[88]

This seems to be the end of Rögnvald’s story – his death in 921. But is it? Several historians have suggested that Rögnvaldr didn’t die in northern England in 921 but actually went on the take the leadership of the Northmen of the Loire in the kingdom of the western Franks, where a certain viking leader called Ragenold is reported in French sources as being active between 921 and his death in 925. Sir Henry Howorth wrote in ‘Ragnall Ivarson and Jarl Otir’ in 1911:

As a matter of fact, he (Ragenold or Rögnvaldr) no doubt soon after this (i.e. his reported death in 921) left the British isles to resume his career in the west of France, where he was probably ambitious to rival the successful doings of Rolf the Ganger, who had founded a new state in Neustria.[89]

Rolf the Ganger means the viking (‘Normand’) the French called Rollo, who became the first Norse duke of Normandy in 912.

Rollo’s tomb in Rouen

References and other relevant works

ARNOLD, Thomas, ed., Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia, Reum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores 75, 2 vols (London, 1882-85)

CAMPBELL, Alistair, ed. and trans., Chronicon Athelweardi: The Chronicle of Aethelweard, Nelson’s Medieval Texts (Edinburgh, 1962)

CLARKSON, Tim, The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland (Edinburgh, 2010)

DE LA BORDERIE, Arthur Le Moyne, Histoire de Bretagne, Vol 2, Second Edition, (Rennes, 1896-1914)

DOWNHAM, Claire, ‘The Historical Importance of Viking-Age Waterford’, Journal of Celtic Studies, 4 (2005), 71-96.

DOWNHAM, Claire, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland. The Dynasty of Ivarr to A.D. 1014 (Edinburgh, 2007)

DUMVILLE, David N., ed. and trans., Annales Cambriae, A.D. 682-954: Texts A-C in Parallel, Basic Texts for Brittonic History 1 (Cambridge, 2002)

EKWALL, Eilert, Scandinavian and Celts in the North-West of England (Lund, 1918)

EKWALL, Eilert, The Place-Names of Lancashire (Manchester, 1922)

FERGUSON, Robert, The Northmen of Cumberland and Westmorland (London, 1856),

Forester, Thomas, ed. and trans., The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester with the two Continuations (London, 1854)

GRAHAM-CAMPBELL, James, ‘The Northern Hoards’, in Edward the Elder, 899-924, edited by N. J. Higham and D. H. Hill (London, 2011), pp. 212-29

GRAHAM-CAMPBELL, James, Viking Treasure from the North-West, the Cuerdale Hoard in its Context, National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside (Liverpool, 1992)

GRIFFITHS, David, Vikings of the Irish Sea: Conflict and Assimilation A.D. 790-1050 (Stroud, 2010)

HENNESSY, William M, ed. and trans., Chronicum Scotorum: A Chronicle of Irish Affairs, from the Earliest Times to A.D. 1135, with a Supplement containing the Events from A.D. 1114 to A.D. 1150, Rerum Brittannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores 46 (London, 1866)

HIGHAM, Nick, ‘The Scandinavians in North Cumbria: Raids and Settlements in the Later Ninth to Mid Tenth Centuries’, in The Scandinavians in Cumbria, edited by John R. Baldwin and Ian D. Whyte, Scottish Society for Northern Studies 3 (Edinburgh, 1985), pp. 37-51

HIGHAM, Nichols, ‘The Viking-Age Settlement in the North-Western Countryside: Lifting the Veil?’ in Land, Sea and Home: proceedings of a Conference on Viking-Period Settlement, at Cardiff, July 2001, edited by John Hines et al. (Leeds, 2004), pp. 297-311

HINDE, John Hodgson, ed., Symeonis Dunelmensis Opera et Collectanea (Durham, 1868)

HOWTON, Sir Henry H., ‘Ragnall Ivarson and Jarl Otir’, in The English Historical Review, Vol 16 (London, 1911), pp. 1-19

HUDSON, Benjamin, Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion, and Empire in the North Atlantic (New York, 2005)

JESCH, Judith, ‘Scandinavian Wirral’, in Wirral and its Viking Heritage, edited by Paul Cavill et al (Nottingham, 2000), pp.1-10

JOHNSON-SOUTH, Ted, ed. and trans., Historia de Sancto Cuthberto. A History of Saint Cuthbert and a Record of his Patrimony, Anglo-Saxon Texts 3 (Cambridge, 2002)

LEWIS, Stephen M., The first Scandinavian settlers of England – the Frisian Connection (Bayonne, 2014)

LEWIS, Stephen M., The first Scandinavian settlers in North West England (Bayonne, 2014)

LEWIS, Stephen M., North Meols and the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire (Bayonne, 2014)

LEWIS, Stephen M., Grisdale 1332 (Bayonne, 2014)

LIVINGSTON, Michael, ed., The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook (Exeter, 2011)

MAC AIRT Sean, and Gearoid MAC NIOCAILL, ed. and trans., The Annals of Ulster (to A.D. 1131), 1 (Dublin, 1983)

MURPHY, Denis, ed., The Annals of Clonmacnoise, being Annals of Ireland from the Earliest Times to A. D. 1408, Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, (Dublin , 1896)

O’DONOVAN, John, ed. and trans., Annala Rioghachta Eireann, Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, from the Earliest Period to the year 1616, second edition, & vols (Dublin, 1856)

O’DONOVAN, John, ed. and trans., Annals of Ireland: three Fragments copied from Ancient sources by Dubhaltach Mac Firbisigh, Publications of the Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society 4 (Dublin, 1860)

MERLET, René, La Chronique de Nantes, (Paris, 1896)

RADNER, Joan Nelson, ed. and trans., Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, (Dublin 1978)

SALMON, André, ed. and trans., Recueil de Chroniques de Touraine. (Supplément aux Chroniques de Touraine), Published by the Société Archéologique de Touraine (Tours, 1854)

SKENE, William F., Chronicles of the Picts and Scots: And Other Memorials of Scottish History (Edinburgh, 1867

STEENSTRUP, Johannes, Normannerne, Vol 1 (Copenhagen, 1876)

STEVENSON, Joseph, trans., Church Historians of England, 8 vols: vol. 3 (part 2: The Historical Works of Simeon of Durham) (London, 1858)

STORM, Gustav, Kritiske Bidrag til Vikingetidens Historie (Oslo, 1878)

THORPE, Benjamin, ed. and trans., The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle According to the Several Original Authorities, Vol 2 (London, 1861)

TODD, James Henthorn, ed. and trans., Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh: The War of the Gaedhill with the Gaill; or, The Invasions of Ireland by Danes and Other Norsemen, Reum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores 48 (London, 1867)

VOGEL, Walther, Die Normannen und das Frankische Reich bis zur Grundung der Normandie (799-911) (Heidelberg, 1906)

WAINWRIGHT, F. T., Scandinavian England: Collected Papers (Chichester, 1975)

WHITELOCK, Dorothy, ed., English Historical Documents, Vol 1, Ad 500-1042 (London, 1955)

WOOLF, Alex, From Pictland to Alba 789-1070 (Edinburgh, 2007)

NOTES:

[1] In this article I will use the Norse spelling of personal names except when quoting from an annal or other source when I will use the spellings given there.

[2] He was only called ‘the Boneless’ in much later Icelandic Sagas. In this article I will generally refer to him as Ívarr I.

[3] See Downham, Viking Kings for the full story of this dynasty..

[4] See Downham, The Historical Importance of Viking-Age Waterford.

[5] In Norse names such as Rögnvaldr the final r is dropped in cases other than the nominative, hence the genitive Rögnvald’s.

[6] The Battle of Corbridge. I assume with most modern historians that there was only one battle which took place in 918.

[7] Vogel, Die Normannen, p. 384.

[8] Wainwright, Scandinavian England, p. 226

[9] Forester, The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester, p. 90. John gives the date as 915 but all the other evidence points to 914.

[10] Thorpe, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (ASC), ‘In this year there came a great naval force over hither from the south, from the Lidwiccas.’

[11] The Welsh, as opposed to the British of Cornwall.

[12] Probably a British bishop of Llandaff called Cyfeiliog.

[13] Archenfield, historically a British area centred on the River Wye, now mostly in Herefordshire.

[14] Here Haorld is wrongly spelt Hroald. The Norse name was probably Haraldr

[15] In Somerset.

[16] The island of Flat Holm in the Bristol Channel.

[17] Dyfed in South Wales.

[18] The ‘A’ text of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives a date of 918 which is clearly wrong. The other texts give dates of 914 or 915.

[19] The son of Alfred the Great.

[20] De La Borderie, Histoire de Bretagne p. 349

[21] Ibid. p. 349

[22] Merlet, Chronique de Nantes, p. 80 : ‘Postea vero ordinates est Adalardus, cujus temporibus coepit ebullire rables Normannourum’.

[23] ‘Eodem anno destr(uctu est) monasterium sci (winga) loci a Normannis.’ Referenced in Vogel, Die Normannen.

[24] Iarnkné probably means ‘Iron-Knee’ in Norse.

[25] For example Joan Radnor, Fragmentary Annals.

[26] See Lewis, The first Scandinavian settlers of England – the Frisian Connection

[27] Downham, Viking Kings, p 31. Sigfrøðr was a son of Ívarr I.

[28] The Chronicum Scotorum gives his name as Iercne and the year as 852. The Annals of Ulster call him Eircne and give the date as 851. See Hennessy, Chronicum Scotorum; Mac Airt, Annals of Ulster.

[29] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 914.

[30] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 902

[31] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 914.

[32] When they had arrived in 892 they came with 250 ships and perhaps 12,000 men. Most decided to remain in East Anglia or Northumbria and settle down to farm. Those who returned to France were said to number only 100 men, led by Huncdeus. See Vogel, Die Normannen, p. 371 for a full discussion.

[33] Note that John of Worcester and some versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle date Óttar’s coming to 915, although all the evidence suggests it was 914.

[34] See Lewis, The first Scandinavian settlers in North West England. Also see Livingston, The Battle of Brunanbugh.

[35] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 904.

[36] ‘Hold’ is short for Holdr, a Scandinavian term introduced into England by the Danes and meaning something like ‘freeholder’.

[37] Hálfdan and Eowils were probably joint kings of Danish York. The Mercian Æthelweard names a third Danish king called Inguuar as being killed at Tettenhall, see Campbell, Chronicon. John of Worcester says that kings Hálfdan and Eowils were the brothers of King Hinguar, Forester, The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester. Inguuar/Hinguuar is probably Ívarr showing, if these reports hold any truth, the typical naming patterns within the family of Ívarr 1.

[38] The battle took place somewhere near Tettenhall and Wednesfield, near present day Wolverhampton.

[39] I will return to this idea at a later date.

[40] Downham, Viking Kings, p. 28.

[41] The Mercians refortified and garrisoned Chester in 907, but there was certainly some delay before Ingimundr and his Norse allies tried to take the city.

[42] Although there is a strong case to be made for a later date – perhaps even after the Battle of Brunanburh in 937.

[43] See for example Graham-Campbell, Viking Treasure.

[44] Foirtriu was the land of the Gaelic Picts.

[45] Radner, Fragmentary Annals.

[46] See discussion in Howorth, Ragnall Ivarson.

[47] Howorth, Ragnall Ivarson; Wainwright, Scandinavian England, pp. 174-176.

[48] Although I tend to the view that this interpolated story probably does refer to Corbridge and not Tettenhall.

[49] Downham, Viking Kings, pp. 26-27.

[50] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 914.

[51] See Downham, The Historical Importance of Viking Age Waterford.

[52] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 914.

[53] See Gustav Storm, Kritiske Bidrag til Vikingetidens Historie, p. 136; Vogel, Die Normannen, p. 391.

[54] Munster.

[55] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 915.

[56] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 916.

[57] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 917

[58] In Leinster. For the location of Cenn Fuait see Downham, Viking Kings, p. 31.

[59] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 917.

[60] Todd, Wars of the Gaedhil with the Gael, p. 41.

[61] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 917

[62] Todd, Wars of the Gaedhil with the Gael, p. cc.

[63] This is not stated anywhere in the sources but is likely as we know of the death of three of Ívarr the Boneless’s sons in Ireland prior to the expulsion.

[64] John of Worcester says that Sigtryggr died in 927 ‘at an immature age’. If we take this literally it implies that he was a relatively young man or possibly unmarried.

[65] Another question is who was (were) the father(s) of Rögnvaldr and Sigtryggr, and indeed of the younger Ívarr and the other grandsons of Ívarr: Óláfr and Guðdrøðr. Each could have been a son of any of the three known sons of Ívarr ‘the Boneless’, or perhaps, as has been suggested, Rögnvaldr and Sigtryggr were the sons of one of Ívarr’s daughters. We simply don’t know. See Downham, Viking Kings, pp. 28-29.

[66] See the chapters on Armounderness in Wainwright, Scandinavian England.

[67] Woolf, From Pictland, p. 131.

[68] Radner, Fragmentary Annals, p. 169.

[69] For example see Woolf, From Pictland, p. 133.

[70] Woolf, From Pictland, p. 132; Johnson-South, Historia de Sancto Cuthberto, paragraphs 21 and 22

[71] Alex Woolf suggests in From Pictland (pp. 143-144) that Cutheard died in 918 not 915. But even if this is so we know from the Historia that Alfred had been settled on his new lands in eastern Northumbria for some time before Rögnvald’s army arrived there in 918. Tilred succeeded as bishop after Cutheard’s death.

[72] Ferguson, The Northmen in Cumberland and Westmorland, p. 11, suggests that in Cumberland the main Norse settlements only really started after 945. See also Wainwright, Scandinavian England, pp. 218-220. I will return to this question in a future article.

[73] Vogel, Die Normannen, p. 386.

[74] See as a start Wainwright, Scandinavian England and Ekwall, Scandinavians and Celts in the North-west of England and Place-names of Lancashire.

[75] Krakabeinn, which is usually taken to mean Crowfoot but as an epithet Bone Breaker would do just as well.

[76] Mac Airr and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 918.

[77] See Johnson-South, ed., Historia de Sancto Cuthberto.

[78] See Skene, The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

[79] Woolf, From Pictland, p.144.

[80] For the view that there were see F. W. Wainwright The Battles at Corbridge in Scandinavian England.

[81] Stevenson, The Church Historians, 111, pt 2, p.68; Arnold, Historia Regum Anglorum, Part 1 (Symeonis Monarchi Opera), 2, 93.

[82] We should add here that under the year 912 the Historia Regum tells of a King Ivarr and jarl Ottar plundering ‘Dunbline’. Most historians suggest the year referred to in 918. This could be Dunblane in Perthshire or Dublin in Ireland. I tend to agree with Downham that this entry most probably suggests that the ‘army of Waterford assisted in the capture of Dublin in 917 and overwintered there before proceeding to England’. See Downham, Viking Kings, p.143.

[83] Downham, Viking Kings, p. 92.

[84] This reminds me of the on-going debate regarding the location of the important Battle of Brunanburh in 937. See for example the discussions in The Battle of Brunanburh – A Casebook, ed. Livingston.

[85] Clarkson, The Men of the North; Woolf, From Pictland, pp. 152-57

[86] Woolf, From Pictland, p. 146.

[87] Arnold, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

[88] Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 921.

[89] Howorth, Ragnall Ivarson,