‘And in the same yere an heretyke called with the longe berd was drawen and hanged for heresye and cursed doctrine that he had taught.’ Chronicle of London, 1196

‘He (King Richard) used England as a bank on which to draw and overdraw in order to finance his ambitious exploits abroad.’ A. L. Poole in the Oxford History of England

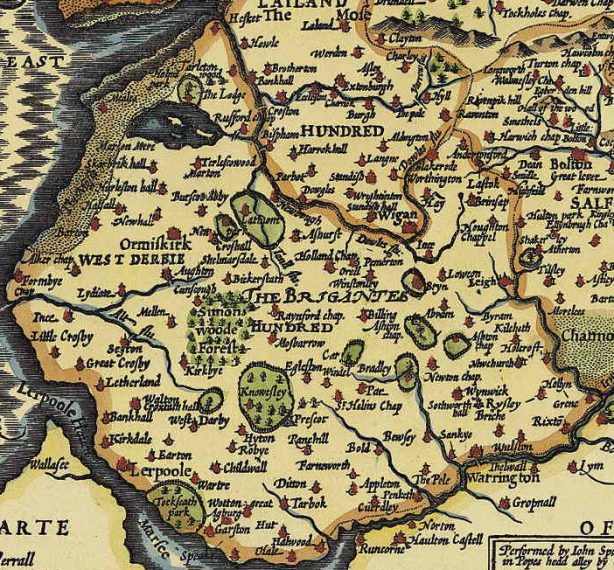

One spring night in the year 1190, a group of ten military transport ships en route for Lisbon was caught in a tremendous storm off the coast of Spain. The ships were part of a flotilla of over a hundred transports taking thousands of English and French soldiers to join Richard Coeur de Lion, the French king of England, in Marseilles. Richard had decided to join the third crusade to the Holy Land, there to join his Frankish cousins in their attempt to expel Saladin’s Muslim Saracens and retake Jerusalem. On one of the ships caught in the storm were over a hundred Londoners. One was William Fitz Osbert, who would later be called Longbeard because, wrote the greatest of England’s early medieval historians, Matthew Paris, he and his kinsmen had ‘adhered to this ancient English fashion of being bearded as a testimony of their hatred against their Norman masters’. William’s story can tell us much about life in England, and particularly in London, at the end of the twelfth century. Over a hundred years after the Norman Conquest the English were still suffering at the hands of their French conquerors.

A Child’s History of England by Charles Dickens

This is not a mystery tale, so here I’ll let the inimitable Charles Dickens summarize what happened to William.

There was fresh trouble at home about this time, arising out of the discontents of the poor people, who complained that they were far more heavily taxed than the rich, and who found a spirited champion in William Fitz-Osbert, called Longbeard. He became the leader of a secret society, comprising fifty thousand men; he was seized by surprise; he stabbed the citizen who first laid hands upon him; and retreated, bravely fighting, to a church, which he maintained four days, until he was dislodged by fire, and run through the body as he came out. He was not killed, though; for he was dragged, half dead, at the tail of a horse to Smithfield, and there hanged. Death was long a favourite remedy for silencing the people’s advocates; but as we go on with this history, I fancy we shall find them difficult to make an end of, for all that. Charles Dickens. A Child’s History England. 1852.

The Sources for William’s life

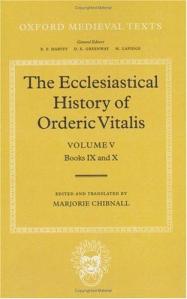

Matthew Paris

We are lucky because four contemporary chroniclers wrote about William’s life and death: William de Newburgh, Roger of Hoveden, Gervase of Canterbury and Ralph de Diceto. Hostile as most of them were, they are our primary sources for the story I will tell. Their testimony, and some of them witnessed some of the events, is supplemented by the slightly later narratives of Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris, as well as by evidence from contemporary legal reports and two short entries in chronicles of London, one of which was quoted at the start of this article.

Who was William Longbeard?

It is believed that William was a Londoner, the son of ‘Osbert the Clerk’. The family wasn’t rich but was certainly well-to-do. William had been able to study law at university, supported partly by his brother Richard. In order to raise the money needed to go on crusade William had leased or mortgaged his London house to his brother Richard. Richard will reappear later in our story in not very fraternal circumstances.

In Portugal

Angevin Ship

The story of the storm and what happened to William and his fellow Londoners in Portugal is told by Roger of Hoveden (Howden). Hoveden had also joined the king’s crusade and was in all likelihood aboard one of the English ships in the flotilla that left England around Easter 1190. Indeed, because of the tremendous detail included in his story we can conjecture that Hoveden was on board one of the ten ships caught in the storm off the coast of Spain.

Having left Dartmouth these ten ships set sail for Lisbon. I will let Roger Hoveden tell what happened then:

When they had now passed through the British Sea and the Sea of Poitou, and had come into the Spanish sea, on the holy Day of the Ascension of our Lord, at the third hour of the day, a mighty and dreadful tempest overtook them, and in the twinkling of an eye they were separated from each other.

While the storm was raging, and all in their afflictions were calling upon the Lord, the blessed Thomas, the archbishop of Canterbury and Martyr, appeared at three different times to three different persons, who were on board a London ship, in which was William Fitz Osbert, and Geoffrey, the goldsmith, saying to them, “ Be not afraid, for I, Thomas the archbishop of Canterbury, and the blessed Edmund the Martyr, and the blessed Nicholas the confessor, have been appointed by the Lord guardians of this fleet of the king of England; and if the men of this fleet will guard themselves against sin, and repent of their former offense, the Lord will grant them a prosperous voyage, and will diet their footsteps in His paths.”

After having thrice repeated these words, the blessed Thomas vanished from before their eyes, and immediately the tempest eased, and there was a great calm on the sea.

The murder of Thomas a Becket

The divine intervention of St. Thomas a Becket and the other saints had put an end to the storm. The Londoners’ ship had been swept past Lisbon and eventually came to anchor off the Portuguese town of Silves. Silves, Hoveden wrote, was which in those days was ‘the most remote of all the cities of Christendom, and the Christian faith was as yet but in its infancy there’, it having only been captured from the Moors by King Sancho I of Portugal the year before. The Londoners, including William, came ashore in a boat and were warmly welcomed by the bishop, clergy and Christian townspeople of the town because they knew that the Moorish ‘Emir’ might soon be coming to reclaim the town and thus they needed these ‘hundred young men of prowess’ who were very ‘well armed’ to help them fight off the Moors.

Fearing that these warriors might depart without helping them, the townspeople broke up their ship and ‘with the timbers of it made bulwarks for the city’, promising recompense later. With the help of the London crusaders the town prepared to defend itself.

In the meantime Botac El Emir Amimoli, emperor of Africa and of Saracenic Spain, levying a large army, marched into the territories of Sancho, king of Portugal, to take vengeance for the emperor of Africa, his father, who had died six years before while besieging Santa Erena, a castle of king Alphonso, father of the said Sancho, king of Portugal.

The ‘Botac El Emir Amimoli, emperor of Africa and of Saracenic Spain’, to whom Hoveden refers, was actually the Almohad Caliph Abu Yusuf Ya’qub al-Mansur also known as Moulay Yacoub.

Succeeding his father, al-Mansur reigned from 1184 to 1199. His reign was distinguished by the flourishing of trade, architecture, philosophy and the sciences, as well as by victorious military campaigns in which he was able to temporarily stem the tide of Christian Reconquista in the Iberian Peninsula

Silves in Portugal today

While all this was going on, the other nine ships that had been caught in the storm had made it to Lisbon. King Sancho sent envoys to them and ‘asked succours of them against the Saracens’. Cutting a long story short, the Portuguese king was ‘utterly destitute of resources and counsel,’ and as he had ‘but few soldiers… mostly without arms,’ was emboldened by the arrival of five hundred well-armed French and English and rebuffed the ‘emir’s’ offer to leave Portugal if he were given back the town of Silves.

On hearing of the arrival of the foreigners, the emperor was greatly alarmed, and, sending ambassadors to the king of Portugal, demanded of him Silva, on obtaining which, he would depart with his army, and restore to him the castle which he had taken, and would keep peace with him for seven years; but when the king of Portugal refused to do this, he sent him word that on the following day he would come to lay siege to Santa Erena. (Hoveden)

The Portuguese and their temporary French and English allies prepared to defend the town of Santa Erena, but suddenly news came that the Emir was dead and his army in flight. Actually Abu Yusuf Ya’qub al-Mansur didn’t die until 1199, but in any case Sancho was safe for the time being.

King Sancho I

Sancho thanked ‘the strangers’ and promised he would reward them handsomely. However, before they got back to their ships to continue on their journey to join Richard at Marseilles, sixty-three more transport ships of the king of England arrived in Lisbon, led by the Norman knights Robert de Sablé and Richard de Canville and comprising Richard’s Norman, Angevin and Breton fighters. Some of these new arrivals then proceeded to commit atrocities, as was the wont of most Frankish crusaders. Hoveden tells us that having disembarked ‘some evil doers and vicious persons… then committed violence upon the wives and daughters of the citizens (of Lisbon)’. ‘They also drove away the pagans and Jews, servants of the king, who dwelt in the city, and plundered their property and possessions, and burned their houses; and they then stripped their vineyards, not leaving them so much as a grape or a cluster.’

John Gillingham, a modern biographer of Richard I, wrote simply: ‘In an excess of religious zeal they attacked the city’s Muslim and Jewish population, burned down their houses and plundered their property. There was, however, no element of religious discrimination in the freedom with which they raped women and stripped vineyards bare of fruit. Eventually the exasperated king of Portugal shut the gates of Lisbon trapping several hundred drunken men inside the city and throwing them into goal.’

Before Sancho had trapped the crusaders in Lisbon, they had already killed more of the city’s citizens. Finally the Portuguese king, in fear of such a vicious army of crusaders, agreed with them that ‘past injuries should be mutually overlooked’ and the crusaders were thus free to continue their voyage to Marseilles; which after a long and eventful journey they reached in August.

Did William go to the Holy Land?

Where William had been during the time all this was happening in Lisbon is not known. His ship had been dismantled in Silves, but had he and his fellow Londoners rejoined the rest on the fleet bound for Marseilles and from there proceeded to the Holy Land? The records are silent. Yet the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that Portugal was not the end of the crusading journey for William and the other one hundred Londoners caught in the storm. Most, though not all, historians agree.

Richard the Lionheart arriving at Acre

As mentioned previously, Roger of Hoveden’s history provides an immense amount of detail on the events William and his colleagues had been involved in at Silves. He even mentions William by name. Where had Roger heard all this? It seems to be that there are really only two realistic options: either Roger had been with the Londoners at Silves and therefore witnessed events himself, or he had been aboard one of the other nine ships in the flotilla caught in the storm but which had made it safely to Lisbon, and there heard the story of the deliverance of the Londoners when they rejoined the main part of the English fleet.

The English crusader fleet, which certainly included Roger of Hoveden, arrived in Marseilles in August 1190. We hear nothing from him, or from anyone else, about the hundred Londoners returning to England. The most likely scenario is that after their stay in Silves the Londoners had rejoined the fleet in Lisbon or had been picked up in Silves when it passed the town on its way to Marseilles; which Hoveden tells us it did: ‘After this, they passed the port of Silva, which at that time was the most remote city of the Christians in those parts of Spain.’

Richard Massacres the Saracens

I will pass over the deeds and misdeeds of King Richard and his multinational army of crusaders in the Holy Land. Suffice it to say that when the English fleet arrived in Marseilles, Richard had already left with his French army for Sicily. The fleet soon caught up with him, and after much violence there and after capturing Cyprus the crusaders finally made it to the Holy Land at the end of 1190. There they helped their Frankish cousins to capture Acre from Saladin after a long horrific siege. Richard took several thousand Muslim prisoners at Acre, but frustrated when Saladin had stalled the negotiations for their release he promptly massacred nearly 3,000 of them, decapitating them in full view of Saladin’s army.

Saladin stalled for time in the hope that an approaching Muslim army would allow him to retake control of the city. When Saladin refused a request from Richard to provide a list of names of important Christians held by the Saracens, Richard Coeur de Lion took this as the delaying tactic that it probably was, and insisted that the ransom payment and prisoner exchange should occur within one month. When the deadline was not met Richard became infuriated and decided on a savage punishment of Saladin for his perceived intransigence. Richard personally oversaw and planned the massacre which took place on a small hill called Ayyadieh, a few miles from Acre. The killings were carried out in full view of the Muslim army and Saladin’s own field headquarters. Over 3,000 men, women and children, were beaten to death, axed or killed with swords and lances.

If William Longbeard had gone with Richard to the Holy Land, as I think he did, he would have witnessed all this. One historian, Alan Cooper, believes that the horrors William witnessed at Acre had traumatised him and had made him more caring towards the poor and oppressed, and suggests that this might help to explain his subsequent actions back in London. This might well be true but there is no evidence for it.

Return to London

An engraving showing Richard in prison

King Richard and his French and English crusaders left the Holy Land in mid 1192, having failed to capture Jerusalem. The English contingent took ship and returned to England, but Richard, being a French-speaking Frenchman, wanted to get back to his French territories as soon as possible to continue his wars with the French king Philip Augustus. After being forced by bad weather to put in at Corfu, Richard was then shipwrecked at Aquileia and therefore set out overland with only a few guards. This was a mistake as shortly before Christmas 1192 he was captured near Vienna by his enemy Leopold V, Duke of Austria, who accused Richard of arranging the murder of his cousin Conrad of Montferrat. Richard was to remain a prisoner for until February 1194. A huge ransom was raised from his ever-suffering English subjects to secure his release.

One way or another William Fitz Osbert also made his way home to London, whether he was already long-bearded or not we don’t know. And here we finally come to the heart of William’s story. It’s all about money and tax. One of my favourite historians, Joseph Clayton, wrote in his Leaders of the People; Studies in Democracy:

Richard Coeur de Lion, occupied with the crusades, had no mind for the personal government of England. He depended on his ministers for money to pay for his military expeditions to Palestine. England was to him nothing more than a subject province to be bled by taxation.

This is undoubtedly true, although we might add that the French king of England also used his English realm as an abundant source of soldiers to fight in his wars; as he did his continental possessions too. But it was the English who had to pay for it all, and London, being the largest and most important city, had to bear the largest share, including for King Richard’s massive ransom.

Taxing London

Errol Flynn as Robin Hood

This was an intolerable burden on the English, a memory that was later to find its way into English folklore in the form of Robin Hood, Richard’s evil brother John and the Sheriff of Nottingham.

But as always the rich and powerful tried, and often succeeded, in getting out of their duty to pay their share of these intolerable taxes. The burden fell on the poor.

When William Fitz Osbert returned to London from the Holy Land, probably in 1193, the people of London were once again being asked to raise a huge sum to pay the ransom needed to ensure King Richard’s release from captivity. Historian John McEwan puts it as follows:

In the 1190s, taxation was the immediate cause of the tensions between the rich and poor people of London. King Richard 1 needed funds to support his wars and crusading ambitions, and he placed a severe burden on the entire kingdom. In 1188 there had been a levy for the aid of Jerusalem, known as the ‘Saladin Tithe’. In 1193 the people had been called upon to contribute to the king’s ransom and then, just a year later in 1194, there had been another tax. These levies came over and above the regular sums extracted from the city, such as the farm, which was paid once a year. The crown’s exceptional demand on the city brought taxation to the forefront of the civic political agenda.

An Anglo-Saxon Folkmoot

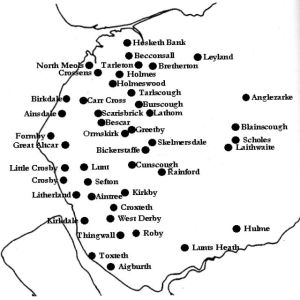

We know that at this time collecting such taxes and levies was ‘left to Londoners themselves’. The aldermen of each city ward met at the ‘wardmoot’, an institution that went back to Anglo-Saxon times. Consent needed to be obtained and then each citizen was meant to contribute according to his wealth, although normally wealthier citizens were expected to pay at a higher rate than poorer people. If anyone possessed a ‘stone house’ they were deemed to be wealthy and ‘singled out and required to contribute at a higher rate’.

But this excellent Anglo-Saxon custom was being increasingly bypassed and ignored by the wealthier citizens of London, many of whom were the French-speaking descendants of the Norman conquerors; the poor being mostly the English.

The great early nineteenth century historian Sir Francis Palgrave put it thus:

Great and frequent were the talliages imposed upon the City of London, for Richard’s ransom: and the burthen, according to the popular opinion, was increased, by the inequality of its apportionment or repartition. London at this period, contained two distinct orders of citizens: the Aldermen, the “Majores” or “Nobiles”, as they are termed in the ancient Year Books of the City, the Patricians or higher order, constituting (as they asserted) the municipal Communia, and constantly exercising the powers of government. To these, were opposed the lower order, who — perhaps being subdivided amongst themselves into two tribes of plebeians — maintained that they were the true Communia, to which, as of right, the municipal authority ought to belong. And in these conflicting ranks, an historical theorist may suppose that he discovers the vestiges of the remote period, when London was inhabited by distinct races or nations, each dwelling in their own peculiar town — the Ealdormannabyrigy still known as the Aldermanbury — inhabited by the nobles or conquering caste: whilst the rest of the city was peopled by the tributary or subject community. All contemporary chroniclers tell the same story: there was massive discontent because the wealthy and powerful were trying to avoid their share of the levy being raised to pay the king’s ransom.

Indeed.

Ralph de Diceto, the French-born Dean of St. Paul’s, wrote that he had noticed tension building ‘between the rich and poor concerning the apportioning of the taxes payable to the treasury according to everyone’s means’. Roger of Hoveden said that ‘strife originated amongst the citizens of London, for not inconsiderable aids were imposed more often than usual because of the king’s imprisonment and other incidents, and in order to spare their own purses the rich wanted the poor to pay everything’. William of Newburgh wrote that Fitz Osbert claimed that ‘on the occasion of every royal edict the rich spared their own fortunes and because of their power placed the whole weight on the poor and defrauded the royal treasury of a large sum’.

Ralph de Diceto, the French-born Dean of St. Paul’s, wrote that he had noticed tension building ‘between the rich and poor concerning the apportioning of the taxes payable to the treasury according to everyone’s means’. Roger of Hoveden said that ‘strife originated amongst the citizens of London, for not inconsiderable aids were imposed more often than usual because of the king’s imprisonment and other incidents, and in order to spare their own purses the rich wanted the poor to pay everything’. William of Newburgh wrote that Fitz Osbert claimed that ‘on the occasion of every royal edict the rich spared their own fortunes and because of their power placed the whole weight on the poor and defrauded the royal treasury of a large sum’.

London’s poor resented rich Londoners for not paying their fair share as much as they resented the exorbitant taxes themselves. This was certainly the view of William Fitz Osbert, who felt that it was unjust.

By 1194 King Richard’s ransom had been collected from the citizens of London and from the rest of the country, and early that year Richard returned to England for a brief visit. In fact Richard only every spent two very brief periods in England in his whole life, amounting in total to less than six months. When he wasn’t on crusade or being held captive, he was otherwise constantly hacking his way through France, defending his vast territories there, and battling his countryman, the king of France, Philip Augustus.

Richard 1

The 1902 Encyclopaedia Britannica had this to say about Richard:

Personally Richard, though born on English ground, was the least English of all our kings. Invested from his earliest years with his mother’s Southern dominions, Richard of Poitou had little in him either of England or of Normandy: he was essentially the man of Southern Gaul. Twice in his reign be visited England; to be crowned on his first accession, to be crowned again after his German captivity. The rest of his time was spent in his crusade, and in various continental disputes which concerned England not at all, except so far as she had to pay for them. The mirror of chivalry was the meanest and most insatiable of all the spoilers of her wealth. For England, as a kingdom, all that he did was to betray her independence by a homage to the emperor, which formed a precedent for a more famous homage in the next reign.

Though born in Oxford, Richard spoke no English. The English constitutional historian William Stubbs wrote:

He was a bad king: his great exploits, his military skill, his splendour and extravagance, his poetical tastes, his adventurous spirit, do not serve to cloak his entire want of sympathy, or even consideration, for his people. He was no Englishman, but it does not follow that he gave to Normandy, Anjou, or Aquitaine the love or care that he denied to his kingdom. His ambition was that of a mere warrior: he would fight for anything whatever, but he would sell everything that was worth fighting for. The glory that he sought was that of victory rather than conquest.

William accuses his brother of treachery

During Richard’s few months on this his second, and last, visit to England in 1194, William Fitz Osbert, who, as has been mentioned, had probably met Richard while they were together on crusade, took the unusual step of denouncing his own brother, Richard Fitz Osbert, and two other wealthy Londoners to the king. He claimed they were not only avoiding paying their fair share of the taxes that were still being raising for Richard’s campaign plans in France, but that they were traitors as well.

William of Newburgh wrote:

At last, a cruel and impudent act of his against his own brother served as a signal for his fury and wickedness against others; for he had an elder brother in London from whom, during the period, when he was at school, he had been accustomed to solicit and receive assistance in his necessary expenses: but when he grew bigger and more lavish in his outlay, he complained that this relief was too tardily supplied to him, and endeavoured by the terror of his threats to extort that which he was unable to procure by his entreaties. Having employed this means in vain, his brother being but little able to satisfy him (owing to his being busied with the care of his own household) — and raging, as it were, for revenge, he burst out into crime; and thirsting for his brother’s blood after the many benefits which he had received from him, he accused him of the crime of high treason. Having come to the king, to whom he had previously recommended himself by his skill and obsequiousness, he informed him that his brother had conspired against his life — thus attempting to evince his devotion for his sovereign, as one who, in his service, would not spare even his own brother; but this conduct met with derision from the king, who probably looked with horror on the malice of this most inhuman man, and would not suffer the laws to be polluted by so great an outrage against nature.

Ralph de Diceto, the Dean of St. Paul’s, was even more damning. He said that William ‘in his meetings pursued to the death his carnal brother and two other men of good repute as if they were guilty of betraying the king’.

Summarizing the evidence of these two chroniclers, Sir Francis Palgrave wrote:

Summarizing the evidence of these two chroniclers, Sir Francis Palgrave wrote:

William with the long beard had an elder brother, Richard Fitz Osbert. To this relative he had been indebted for support when young, and whilst pursuing his studies. Extravagant and profuse in more advanced age, William attempted to encroach upon Richard’s bounty, and strove to obtain by threats, the relief which had been denied to his solicitations. He now sought the blood of this near kinsman, persecuting him to the death with the utmost virulent hostility.

William went personally to see the king, who was still in England, and ‘availing himself of the intimacy which he had acquired he denounced Richard Fitz-Osbert as a traitor, a conspirator against the life of the king’.

Longbeard repaired to Coeur de Lion; and, availing himself of the intimacy which he had acquired, he denounced Richard Fitz-Osbert as a traitor, a conspirator against the life of the King. Such was his devotion towards his Sovereign, he declared, that he would not spare his brother at the expense of his allegiance. (Palgrave)

The intimacy to which Palgrave refers was, he suggested, due to the fact that William had got to know the king during their time together on the third crusade. There seems to be no other explanation, and most historians concur.

William of Newburgh said that the accusation was spurned by the king because of his horror at such natural cruelty. Even a conservative like Palgrave had to demur; he asked whether ‘Richard, who was himself so devoid of natural affection, could be actuated by such a motive’.

English Pipe Roll

We are fortunate that there is in the English Pipe Rolls an account of the proceedings in the case. Palgrave, the editor of the Pipe Rolls, summarizes what happened in November 1194:

It appears, then, by the entries upon the Roll, that on the Morrow of St. Edmund, in the sixth year of Richard I., William Fitz Osbert preferred his appeal before the Justices at Westminster against Richard Fitz Osbert, his brother. Speaking as a witness — for every Appellant supported his complaint by his own positive testimony — he affirmed that a meeting was held in the “stone house” of the said Richard, when a discussion arose concerning the aids granted to the King for his ransom. Richard Fitz Osbert exclaimed, “In recompense for the money taken from me by the Chancellor within the Tower of London, I would lay out forty marks to purchase a chain in which the King and his Chancellor might be hanged.”

There were others present who heard this speech, Jordan the Tanner and Robert Brand, without doubt the two true men noticed, but not named, by Ralph de Diceto, whose brief account of the transaction agrees, so far as it extends, with the record. And they also vied with Richard Fitz Osbert in his disloyalty. “Would that the King might always remain where he now is,” quoth Jordan. In this wish Robert Brand cordially agreed. And, “Come what will,” they all exclaimed, “in London we never will have any other King except our Mayor; Henry Fitz Ailwin of London Stone”.

As was mentioned earlier, one of the signs that a Londoner was wealthy was if he possessed a stone house; and here is an explicit mention that Richard Fitz Osbert’s meeting took place in his ‘stone house’.

We know from elsewhere that both Jordan the Tanner and Robert Brand were both quite well-to-do London merchants. In later years they would often appear as witnesses on documents drawn up by the Mayor of London Henry Fitz Ailwin, who is referred to in William’s testimony.

It’s also important to notice that the Pipe Rolls tell us there were several others witnesses who agreed with the testimony William gave against his brother and the two other wealthy London merchants. In many ways the evidence suggests that it was actually William Fitz Osbert, the Longbeard, who was being most loyal to the king here. His brother had, after all, declared that he ‘would lay out forty marks to purchase a chain in which the King and his Chancellor might be hanged’. All three defendants had also agreed that ‘the King might always remain where he now is’, i.e. by now back home in France. In many ways the three defendants were being much more revolutionary than was William, who remained loyal to Richard and only wanted that the tax burden was shared fairly. The key difference being, as we will see, that Richard and his friends had gone in for a bit of revolutionary pub-talk, which they soon retracted, while William was to take his message to the common people, a much more dangerous thing.

compurgators

Following the procedure at the time (and now) the defendants, or ‘appellees’, were then given their chance to reply. They denied the whole accusation ‘de verbo in verbum’ i.e. word for word. They asked that they be acquitted and demanded their right as citizens to defend themselves ‘by compurgation, according to the old Anglo-Saxon laws of their ancestors’.

In pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon times, a defendant ‘could establish his innocence by taking an oath and by getting a required number of persons, typically twelve, to swear they believed the defendant’s oath’. Now this system had always been open to abuse by the rich and powerful. Not only could rich defendants simply bribe witnesses to corroborate their oaths, but the oaths of rich or propertied people also counted for more than those of the poor. Nevertheless, the twelve people were the basis of the jury system in the present-day ‘Anglo-Saxon’ world.

Proceedings were then adjoined and ‘the Sunday next after the feast of St. Katherine’ (i.e. in three weeks time), was fixed as the date for the hearing to continue. The three defendants, Richard Fitz Osbert, Jordan the Tanner and Robert Brand (who remember were on trial for the capital offense of treason), had to find persons who would pledge that they would reappear – i.e. people who in modern parlance would post a bail bond. The names of these pledge givers were recorded and included ‘many well-known names of citizens and civic families’. Palgrave commented: ‘The case of the appellees was therefore defended by the Magnates, to whom William with the long bearde was so much opposed.’

The date when the hearing was to reconvene at Westminster was then shifted to 21 December 1194, ‘on Sunday before Christmas next – to wit on the octaves of St. Hilary’. The text of the Pipe Roll then becomes unreadable, but, as Palgrave commented: ‘We can ascertain that the facts have been mistold by Neubrigensis (William of Newburgh).’ He added:

The accusation was followed up in due form of law before the Justices at Westminster, and without any reference to the King.

We don’t have the eventual verdict, but it seems reasonably clear that either the defendants were acquitted of treason or the suit against them was dropped, because they continued to be prominent citizens of London for some years to come.

Before we take the story further, it might be pertinent to ask if William was really motivated solely by spite and envy as some of the chroniclers say. When William had left on crusade, he had leased or mortgaged his house in London to his brother Richard. Perhaps Richard hadn’t paid all he owed? The earliest known reference to William Fitz Osbert is in the 1189 Pipe Roll, before he went on the Crusade, when he is mentioned as owing £40 for a writ he has taken out against another Londoner.

We must admit we don’t really know William’s motives for accusing his brother of treason. William was certainly very loyal to King Richard and it’s possible that when he had heard his brother promising not to pay anymore to the King, and indeed wishing him gone or dead, it was all too much for him when his rich brother either wouldn’t lend him any more money or, possibly, wouldn’t pay him the money he owed him. As we know family feuds can escalate, but still it is difficult to believe that William accused his brother of treason, for which he could be hanged, just because he wouldn’t lend him any more money.

The King departed one more for his French wars later in 1194, never to return.

William as a spokesman and leaders of the London poor

It was now, in 1195, that William Fitz Osbert, called Longbeard, started on his short career as a leader of and spokesperson for the ordinary citizens of London. Sometimes he has been called a popular agitator and often, by those hostile to him at the time and later, a dangerous demagogue. Palgrave wrote:

Fitz Osbert now re-appears in the City as a patriot. Those chroniclers who espouse his cause — and the coeval authorities display, most instructively, all the violent party feelings of the age — maintain, that, moved by an ardent zeal for justice and equity, he acted with specious fidelity as the advocate of the poor. Face to face he opposed the Aldermen, on all occasions: asserting that by the corruption of the “Nobiles” the King’s Exchequer was shamefully defrauded; and labouring to effect an equal and impartial assessment of the citizens according to their means.

I’ll return to this question at the end. For now let’s limit ourselves to the facts of what he actually did.

Rerum Angliarum – William of Newburgh

The contemporary chronicler William of Newburgh was only slightly less condemnatory of William Longbeard than some of the other chroniclers when he tells us:

Afterwards, by favour of certain persons, he obtained a place in the city among the magistrates, and began by degrees to conceive sorrow and to bring forth iniquity. Urged onward by two great vices, pride and envy, (whereof the former is a desire for selfish advancement, and the latter a hatred of another’s happiness) and unable to endure the prosperity and glory of certain citizens, whose inferior he perceived himself to be, in his aspiration after greatness he plotted impious undertakings in the name of justice and piety. At length, by his secret labours and poisoned whispers, he revealed, in its blackest colours to the common people, the insolence of the rich men and nobles by whom they were unworthily treated; for he inflamed the needy and moderately wealthy with a desire for unbounded liberty and happiness, and allured the many, and held them fascinated, as it were, by certain delusions, so closely bound to his cause, that they depended in all things upon his will, and were prepared unhesitatingly to obey him as their director in all things whatsoever he should command.

A powerful conspiracy was therefore organized in London, by the envy of the poor against the insolence of the powerful, The number of citizens engaged in this plot is reported to have been fifty-two thousand — the names of each being, as it afterwards appeared, written down and in the possession of the originator of this nefarious scheme. A large number of iron tools, for the purpose of breaking the more strongly defended houses, lay stored up in his possession, which being afterwards discovered, furnished proofs of a most malignant conspiracy. Relying on the large number who were implicated by zeal for the poorer classes of the people, while he still kept up the plea of studying the king’s profit, he began to beard the nobles in every public assembly, alleging with powerful eloquence that much loss was occasioned to the revenue through their dishonest practices; and when they rose up in indignation against him in consequence, he adopted the plan of sailing across the sea, for the purpose of lamenting to the king that he should have incurred their enmity and calumny in the execution of his service.

Roger of Hoveden wrote:

In the same year, a disturbance arose between the citizens of London. For, more frequently than usual, in consequence of the king’s captivity and other accidents, aids to no small amount were imposed upon them, and the rich men, sparing their own purses, wanted the poor to pay everything. On a certain lawyer, William Fitz-Osbert by name, or Longbeard, becoming sensible of this, being inflamed by zeal for justice and equity, he became the champion of the poor, it being his wish that every person, both rich as well as poor, should give according to his property and means, for all the necessities of the state …

William was a very charismatic speaker. Even his most rabid critic, Gervase, a monk of Canterbury, had to admit that though William was ‘poor in degree, evil favoured in shape’, he was ‘most eloquent’ and ‘moved the common people to seek liberties and freedom, and not to be subject to the rich and mighty; by which means he drew to him many great companies, and with all his power defended the poor men’s cause against the rich’. William of Newburgh said, ‘he was of ready wit, moderately skilled in literature, and eloquent beyond measure,’ but added that ‘wishing, from a certain innate insolence of disposition and manner to make himself a great name, he began to scheme new enterprises, and to venture upon the achievement of mighty plans’.

William was a very charismatic speaker. Even his most rabid critic, Gervase, a monk of Canterbury, had to admit that though William was ‘poor in degree, evil favoured in shape’, he was ‘most eloquent’ and ‘moved the common people to seek liberties and freedom, and not to be subject to the rich and mighty; by which means he drew to him many great companies, and with all his power defended the poor men’s cause against the rich’. William of Newburgh said, ‘he was of ready wit, moderately skilled in literature, and eloquent beyond measure,’ but added that ‘wishing, from a certain innate insolence of disposition and manner to make himself a great name, he began to scheme new enterprises, and to venture upon the achievement of mighty plans’.

William’s long beard was obviously something of a wonder to some of the chroniclers. Newburgh commented: ‘William, having a surname derived from his Long Beard, which he had thus cherished in order that he might by this token, as by a distinguishing symbol, appear conspicuous in meetings and public assemblies.’ A little later the great English historian Matthew Paris gave a different interpretation of William’s beard which rings slightly truer. Paris said that William and his kinsmen had adhered to this ancient English fashion of being bearded as a testimony of their hatred against their Norman masters.

From Anglo-Saxon times the citizens of London (as elsewhere in England) had come together in assemblies called folk moots. While not fully democratic in the modern sense, these folk moots were a type of English proto-democracy and even in the late twelfth century, after more than a hundred years under the Norman yoke ordinary Londoners still cherished their lost freedoms and held folk moots, which a recent charter of King Richard had endorsed. In London these folk moots were usually held in St. Paul’s Churchyard. William addressed London’s citizens there. He told them that the taxes imposed to pay for the king’s overseas wars were being levied unfairly and unjustly, and that the poor were being made to pay all, while rich citizens were evading their duty. With his followers William also broke up meeting of the ‘full hustings’, which was the name given to the assemblies of City aldermen who met to agree on taxes and who was to pay what. The rulers in these hustings, we are told, ‘endeavoured to spare their own purses and to levy the whole from the poor’. Matthew Paris said that ‘owing to the craft of the richer citizens the main part of the burden fell on the poor’

William’s following continued to grow and the demands of the Londoners were starting to unsettle the rulers. According to Ralph de Diceto, the Dean of St. Paul’s, William asked the Londoners to make oaths that they would stick by him and each other. He also says that William’s ‘rhetoric was responsible for a riot in St. Paul’s’. As historian John McEwan says, ‘In disrupting official meetings, and by binding the citizens with oaths, Fitz Osbert threatened the established political order.’

Eventually it was said that William’s followers totalled 52,000; others put the figure at 15,000.

William goes to France to plead with the king

Tensions in the capital started to mount, and William decided to go to France to try to enlist the support of King Richard. William of Newburgh wrote that he ‘deemed it necessary to go overseas to complain to the prince that he suffered the enmity of the powerful’. Roger of Hoveden said that he travelled ‘to the King overseas (and) he obtained his peace for himself and the people’.

Statue of Hubert Walter at canterbury cathedral

Whilst we only have Roger of Hoveden’s evidence regarding the reception William got when he met Richard in France, it does seem that it was at least mildly positive. Joseph Clayton wrote: Richard heard the appeal sympathetically enough, for after all, as long as the money was forthcoming, he had no particular desire that the pockets of the rich burghers should be spared at the expense of the poor, but left matters in the hands of Archbishop Hubert the Justiciar.’

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter, was to be Longbeard’s nemesis. Whilst still bishop of Salisbury Walter had accompanied the king on the third crusade. He was the only English prelate to stay the full course of the king’s involvement. He was decidedly a ‘king’s man’ and upon his return to England in April 1193, while Richard was still being held captive, the king wrote to his mother, Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, telling her that Walter should be chosen for the see of Canterbury, which he duly was, though without consultation with the bishops. On 25 December 1193 he was made Chief Justiciar of England, the effective ruler of the country in the king’s absence. After Richard’s fleeting visit to England in 1194, Walter remained justiciar as well as archbishop of Canterbury. Walter was ‘certainly no champion of the poor’. Gerald of Wales said that ‘he was neither gifted with knowledge of letters nor endowed with the grace of lively religion, so in his days the Church of England was stifled under the yoke of bondage’.

If, as seems likely, Richard had received William Longbeard warmly (he was intensely loyal to people who had been with him on his bloody crusade), this apparently annoyed Archbishop Walter enormously.

Hubert Fitz-Walter, archbishop of Canterbury and the king’s justiciary, being greatly vexed at this, issued orders that wherever any of the common people should be found outside the city, they should be arrested as enemies to the king and his realm. Accordingly, it so happened, that at Mid-Lent some of the merchants of the number of the common people of London were arrested at the fair at Stamford, by command of the king’s justiciary. (Hoveden)

William returns to London

Walter wanted to intimidate William’s supporters. Londoners still clung onto certain rights, one of which was the right not to be arbitrarily arrested within the city limits. But when outside London they were fair game for the Archbishop, hence the arrest of some London merchants in Stamford.

Upon his return, the Chief Justiciar or Regent, Archbishop Hubert, was moved to exceeding wrath, we may conjecture that the authority of the latter was restricted, or his discretion impugned. Hubert at once declared himself as the open adversary of William Fitz Osbert in particular, and of the citizens at large. Orders were issued by the Justiciar, that any one of the commonalty found without the walls of the City should be arrested as an enemy to King and Kingdom. Either the franchises of the citizens, or their strength, or perhaps both causes combined, restrained or deterred the Justiciar from attacking them within their own municipal territory. Beyond the city liberties, he did his worst; and, about Mid Lent, several London merchants, attending Stamford Fair, were seized pursuant to his commands. (Palgrave)

The coronation of Philippe II Auguste in the presence of Henry II of England

But the king trusted and needed the archbishop to extract the huge sums he needed for his never-ending French wars against the French king, Philip Augustus. As already mentioned, Richard really had no interest at all in how the monies to pay his multi-national army were raised, as long as the money arrived.

When William had returned to London from France he had soon discovered that any hope he had had regarding the equity of the new taxes being raised were in vain, so he starting addressing the citizens again.

William of Newburgh tells us:

On his return to his own home again he began afresh, with his accustomed craftiness, to act with confidence, as if under the countenance of the royal favour and to animate strongly the minds of his accomplices. As soon, however, as the suspicion and rumour of the existence of this plot grew more and more confirmed, the lord archbishop of Canterbury, to whom the chief custody of the realm had been committed, thinking disguise no longer expedient, addressed a congregation of the people in mild accents, refuted the rumours which had arisen, and, with a view to remove all sinister doubts on the subject, advised the appointment of hostages for the preservation of the king’s peace and fealty. The people, soothed by his bland address, agreed to his proposal, and hostages were given. Nevertheless, this man, bent upon his object, and surrounded by his rabble, pompously held on his way, convoking public meetings by his own authority, in which he arrogantly proclaimed himself the king or saviour of the poor, and in lofty phrase thundered out his intention of speedily curbing the perfidy of the traitors.

Giving a perhaps more accurate translation of William of Newburgh’s words, Archbishop Walter had ‘convoked the common people, spoke to them squarely… and admonished them to give hostages for being loyal to the king’. Intimidated by Walter’s power the London citizens gave over the demanded hostages, who, as was normal practice, would be killed if the Londoners didn’t remain loyal.

This didn’t stop William Longbeard however. His most rabid critic, Gervase, who was Archbishop Walter’s sacristan at Canterbury, tells us that still ‘supported by the crowd (he) proceeded with a show of pomp and organised public meetings on his own authority.

Palgrave says that William, who was ‘safe within the walls of London, defied the Justiciar and the Royal authority’. His thousands of followers were ‘all arrayed against the rich and noble of the City, who were compelled to watch in arms, day and night, for the purpose of protecting their wealth, their honour, and their lives against this confederacy’.

Old St. Paul’s

William had had no part in the proceedings when the archbishop and justiciar had demanded, and got, hostages from the Londoners. So once again he arranged a folk moot in St. Paul’s Churchyard. ‘He addressed a forcible and energetic discourse to the assembled people, inviting them to defend their case by rallying round him as the Protector of the poor,’

We even know some of the words William was wont to use when addressing the citizens of London at St. Paul’s, and perhaps elsewhere. ‘Having taken his text or theme from the Holy Scriptures, he thus began’:

With joy shall ye draw water out of the wells of salvation [Isaiah 12:3]

And ‘applying this to himself’, he continued:

I am the saviour of the poor. Do ye, oh, poor! who have experienced the heaviness of rich men’s hands, drink from my wells the waters of the doctrine of salvation, and ye may do this joyfully; for the time of your visitation is at hand. For I will divide the waters from the waters. The people are the waters. I will divide the humble from the haughty and treacherous. I will separate the elect from the reprobate, as light from darkness.

The Archbishop seeks William’s arrest

William was by now thoroughly hated by London’s powerful and particularly by Archbishop Walter, who decided that he was a dangerous demagogue and must be stopped. As intimidating his supporters hadn’t worked as much as he had wanted, though it did reduce William’s following and the scale of the protests somewhat, Walter took advice from the nobles and ‘summoned Fitz Osbert to appear and answer the accusations now preferred against him’.

As he possessed a mouth speaking great things, and had horns like a lamb, he spoke like a dragon; and the aforesaid ruler of the realm, by advice of the nobles, summoned him to answer the charges preferred against him. (Newburgh)

But when the time was come for William to appear, he ‘presented himself so surrounded by the populace, that his summoner being terrified, could only act with gentleness, and cautiously defer judgment for the purpose of averting danger’.

The archbishop decided he would have to use stealth to get his hands on William, who by now was deemed a real threat to the rulers of the country. He found two spies, ‘noble citizens’, who were to ‘act as intelligencers’.

Espying out the ways of the declining demagogue, they ascertained how and in what manner he could be safely and surely apprehended. (Palgrave)

Newburgh wrote: ‘The period, therefore, at which it was possible to find him (Longbeard) unattended by his mob being discovered by two noble citizens, especially now that the people, out of fear for the hostages, had become more quiet, he (Walter) sent out an armed force with the said citizens for his apprehension. As one of them was pressing him hard, he slew him with his own axe which he had wrested from his hand, and the other was killed by someone among those who had come to his assistance.’

William seeks sanctuary in St. Mary le Bow

Immediately upon this, he retreated with a few of his adherents and his concubine, who clave to him with inseparable constancy, into the neighbourhood of St. Mary, which is called Le-Bow, with the intention of employing it, not as a sanctuary, but as a fortress, vainly hoping that the people would speedily come to his aid; but they, although grieving at his dangerous position, yet, out of regard for the hostages or dread of the men-at-arms, did not hasten to his rescue. Hearing that he had seized upon the church, the administrator of the kingdom despatched thither the troops recently summoned from the neighbouring provinces. Being commanded to come forth and abide justice — lest the house of prayer should be made a den of thieves — he chose rather to tarry in the vain expectation of the arrival of the conspirators, until the church being attacked with fire and smoke, he was compelled to sally out with his followers: but a son of the citizen whom he had slain in the first onset, in revenge for his father’s death, cut open his belly with his knife. (Newburgh)

St. Mary le Bow

Hoveden tells a similar tale:

The… justiciary then gave orders that… William Longbeard should be brought before him, whether he would or no; but when one of the citizens, Geoffrey by name, came to take him, the said Longbeard slew him; and on others attempting to seize him, he took to flight with some of his party, and they shut themselves in a church, the name of which is the church of Saint Mary at Arches, and, on their refusing to come forth, an attack was made upon them. When even then they would not surrender, by command of the archbishop of Canterbury, the king’s justiciary, fire was applied, in order that, being forced by the smoke and vapour, they might come forth. At length, when the said William came forth, one of them, drawing a knife, plunged it into his entrails, and he was led to the Tower of London…

Gervase of Canterbury simply tells us that William was promised his life if he would quietly surrender; but that he refused ‘to come forth; whereby the Archbishop called together a great number of armed men, lest any stir should be made. The Saturday, therefore, being the Passion Sunday even, the steeple and church of Bowe were assaulted, and William and his accomplices taken, but not without bloodshed for he was forced by fire and smoke to forsake the church, and he was brought to the Archbishop in the Tower…

We are also told that captured with William was his concubine ‘who never left him for any danger that might betide him’. And so, already having been knifed in his entrails, William was ‘secured, bound with fetters and manacles, and carried to the Tower of London’.

The ‘Majores’ of the City and the King’s officers, all joined in urging the Justiciar to inflict a condign punishment upon the offender. Fitz Osbert, by advice of the ‘Proceres’ assembled at the Tower, was condemned to die. (Palgrave)

Hanged in chains at Tyburn

A shameful death for upholding the cause of truth and of the poor. Matthew Paris

The sentence was executed with the usual barbarity. Palgrave writes: ‘Stripped naked, and tied by a rope to the horse’s tail, William was dragged over the rough and flinty roads to Tyburn, where his lacerated and almost lifeless carcass was hanged in chains on the fatal elm’; together with nine of his accomplices.

William Longbeard being dragged to his death at Tyburn

The Dean of St. Paul’s, Ralph de Diceto, probably witnessed William’s journey from the Tower of London to the gibbet at Tyburn, near present-day Marble Arch. He tells us that William ‘his hands tied behind him, his feet tied with long cords, was drawn by means of a horse through the midst of the city to the gallows near the Tyburn. He was hanged.’ The Canterbury monk Gervase almost gleefully wrote that William was ‘dragged, with his feet attached to the collar of a horse, from the aforesaid Tower through the centre of the city to the Elms (at Tyburn), his flesh was demolished and spread all over the pavement and, fettered with a chain, he was hanged that same day on the Elms with his associates and died’. Newburgh said: ‘Being, therefore, captured and delivered into the hands of the law, he was, by judgment of the king’s court, first drawn asunder by horses, and then hanged on a gibbet with nine of his accomplices who refused to desert him’

Slightly later Roger of Wendover wrote in Flowers of History:

In order that the punishment of one might strike terror into the many, he was deprived of his long garments, and, with his hands tied behind his back, and his feet fastened together, was drawn through the midst of the city by horses to the gallows at Tyburn; he was there hung in chains, and nine of his fellow conspirators with him, in order to show that a similar punishment would await those who were guilty of a similar offence.

All the chroniclers who wrote about William’s life and death wrote in Latin. There are however two short entries under the year 1196 in English. The first is found in the Chronicle of London:

In this yere the kyng come in to Engelond, and tok the castell of Notynghame, and disherited John his brother. And the same yere kyng Richarde was crowned ayeyne at Westm’. And in the same yere an heretyke called with the longe berd was drawen and hanged for heresye and cursed doctrine that he had taughte.

Hanging in chains

second is in the Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London under the date of the 8th of April:

In this yere was one William with the long berde taken out of Bowe churche and put to dethe for herysey.

The Elms near Tyburn were called “the King’s Gallows” and were probably first erected around 1110. Tyburn from the beginning was clearly the King’s gallows for London and Middlesex criminals. That it was placed outside the boundary of the city indicates the administration of the criminal law by the King’s courts instead of by the local or manorial courts. The first recorded execution there is actually that of William Longbeard. It was to remain the main place of execution for London and Middlesex until 1783.

In Alfred Marks’ Tyburn Tree, Its History and Annals it is said:

The manner of execution at Tyburn seen in William Fitz Osbert’s execution was to become the norm later. That is, the condemned criminal, after being drawn to Tyburn on a hurdle or rough sledge by a horse, at Tyburn was first hanged on the gallows, then drawn or disembowelled, and finally quartered, his quarters being placed high in public places as a warning to others. Thus, because Tyburn was the King’s Gallows, those who were guilty of Treason were Hanged, Drawn and Quartered on this spot.

‘Chains’

Actually the evidence tends more towards the view that after being ‘dragged over the rough and flinty roads to Tyburn’ William was then hanged in chains (see here for what this involved). Whether he was subsequently disembowelled (drawn) and quartered is not at all clear. Joseph Clayton sums up William’s sad death:

Just before Easter — the wounded man was stripped naked, tried to the tail of a horse and dragged over the rough stones of the streets of London. He was dead before Tyburn was reached, but the poor broken body, on whom the full vengeance of the rich and mighty had been wreaked, was strung up in chains beneath the gallows elm all the same. Bravely had Longbeard withstood the rulers of the land in the day of his strength; now, when life had passed from him, his body was swinging in common contempt. And with him were nine of his followers hanged. So died William, called Longbeard, son of Osbert, “for asserting the truth and maintaining the cause of the poor”.

Still a threat after death

But William remained a threat to the rulers after his death.

And since it is held that to be faithful to such a cause makes a man a martyr, people thought he deserved to be ranked with the martyrs. For a time multitudes — the very folk who had fallen away from their champion in the hour of battle and need — flocked to pay reverence to the ghastly, bloodstained corpse that hung at Tyburn, and pieces of the gibbet and of the bloodstained earth beneath were carried off and counted as sacred relics. All the great, heroic qualities of the man were recalled. He was accounted a saint. Miracles were alleged to take place when his relics were touched. (Joseph Clayton)

William of Newburgh, though pleased with William death, still admitted that his followers bewailed him bitterly as a martyr. ‘Miracles were wrought with the chain that hanged him. The gibbet was carried off as a relic, and the very earth where it stood scooped away. Crowds were attracted to the scene of his death, and the primate had to station on the spot an armed guard to disperse them.’

He that diggeth a pit shall fall into it; and whoso breaketh down an hedge, a serpent shall bite him” [Eccl. 10:8], the contriver and fomenter of so much evil perished at the command of justice, and the madness of this wicked conspiracy expired with its author: and those persons, indeed, who were of a more healthful and cautious dispositions rejoiced when they beheld or heard of his punishment, washing their hands in the blood of the sinner. The conspirators, however, and seekers after novelty, vehemently deplored his death, taking exception at the rigor of public discipline in his case, and reviling the guardian of the realm as a murderer, in consequence of the punishment which he had inflicted on the mischief-maker and assassin. (Newburgh)

William didn’t become a mike these later English Catholic martyrs, hanged, drawn and quartered

So the citizens of London reviled ‘the guardian of the realm as a murderer’; that is Archbishop Walter. Walter’s own sacristan at Canterbury, Gervase, relates that ‘a sudden rumour spread through the city that William was a new martyr and shone through miracles’. Newburgh’s second chapter concerning William is titled ‘How the common people desired to honour this man as a martyr, and how this error of theirs was extinguished’. I think it worth quoting in full:

The extent to which this man had by his daring and mighty projects attached the minds of the wicked to himself, and how straitly he had bound the people to his interests as the pious and watchful champion of their cause, appeared even after his demise. For whereas they should have wiped out the disgrace of the conspiracy by the legal punishment of the conspirator, whom they stigmatized as impious and approved of his condemners, they sought by art to obtain for him the name and glory of a martyr. It is reported that a certain priest, his relative, had laid the chain by which be had been bound upon the person of one sick of a fever, and feigned with impudent vanity that a cure was the immediate result. This being spread abroad, the witless multitude believed that the man who had deservedly suffered had in reality died for the cause of justice and piety, and began to reverence him as a martyr: the gibbet upon which he had been hung was furtively removed by night from the place of punishment, in order that it might be honoured in secret while the earth beneath it, as if consecrated by the blood of the executed man, was scraped away in handfuls by these infatuated creatures, as something consecrated to healing purposes, to the extent of a tolerably large ditch. And now the fame of this being circulated far and wide, large bands of fools, “whose number,” says Solomon, “is infinite,” [see Eccles 1:15, Vulgate] and curious persons flocked to the place, to whom, doubtless, were added those who had come up out of the various provinces of England on their own proper business to London.

The idiot rabble, therefore, kept constant watch and ward over the spot; and the more honour they paid to the dead man, so much the greater crime did they impute to him by whom he had been put to death. To such an extent did this most foolish error prevail as even to have ensnared, by the fascination of its rumours, the more prudent, had they not used great caution in giving a place in their memory to the stories they heard concerning him. For, in addition to the fact of his having (as we have before narrated) committed murder shortly before his execution, which alone should have sufficed to every judicious understanding as a reason against the punishment being considered a martyrdom, his own confession before death must redden with a blush the countenances of those who would fain make unto themselves a martyr out of such a man, if any blood exist in their bodies. Since, as we have heard from trustworthy lips, he confessed, while awaiting that punishment by which he was removed — in answer to the admonitions of certain persons that he should glorify God by a humble though tardy confession of his sins — that he had polluted with carnal intercourse with his concubine that church in which had sought refuge from the fury of his pursuers, during the stay he had made there in the vain expectation of rescue; and what is far more horrible even to mention, that when his enemies had broken in upon him, and no help was at hand, he abjured the Son of Mary, because he would render him no assistance, and invoked the devil that he at least would save him. His justifiers deny these tales, and assert that they were maliciously forged in prejudice to the martyr. The speedy fall of this fabric of vanity, however, put an end to the dispute: for truth is solid and waxes strong by time; but the device of falsehood has nothing solid, and in a short time fades away.

The administrator of the kingdom, therefore, carrying out the condign punishment of ecclesiastical discipline, sent out a troop of armed men against the priest who had been the head of this superstition, who put the rustic multitude to flight, and capturing those who endeavoured to maintain their ground there by force, consigned them to the royal prison. He also commanded an armed guard to be constantly kept upon that place, who were not only to keep off the senseless people, who came to pray, but also to forbid the approach of the curious, whose only object was amusement. After this had lasted for a few days, the entire fabric of this figment of superstition was utterly prostrated, and popular feeling subsided.

Gervase of Canterbury recorded that ‘an ambush was laid and those who came at night-time to pray were whipped’.

Popular Agitator or Dangerous Demagogue?

The violence ordered by Archbishop Walter had crushed the incipient cult of William Longbeard ‘the Martyr’. As Sir Francis Palgrave said: ‘Hubert the Justiciar was able to chase away the votaries of Fitz Osbert, and to reduce the citizens to obedience’.

In addition, William of Newburgh spread the rumour that while seeking safety in the church of St. Mary le Bow, William ‘had polluted with carnal intercourse with his concubine that church in which had sought refuge from the fury of his pursuers’, that he had confessed to this, and that ‘what is far more horrible even to mention, that when his enemies had broken in upon him, and no help was at hand, he abjured the Son of Mary, because he would render him no assistance, and invoked the devil that he at least would save him’. As if William’s brutal death wasn’t enough, here was an attempt to besmirch William’s name forever; although Newburgh does have the grace to add: ‘His justifiers deny these tales, and assert that they were maliciously forged in prejudice to the martyr.’

So was William Longbeard a popular agitator for the poor of London or, as contemporary chroniclers and many later generations of historians, such as William Stubbs have called him, a dangerous ‘demagogue’? He was clearly both; it all depends whose side you are on.

Joseph Clayton

Whatever his initial motives, it remains a fact that William Fitz Osbert was passionately concerned about the injustice in the way the people of London were being taxed to pay for the adventures of a absent foreign king, a king to whom William always regarded himself as loyal. He spoke for the ordinary citizens and they followed and venerated him. I can’t help but agree with Joseph Clayton:

Longbeard had roused the common working people to make a stand against obvious oppression and injustice — there was the head and front of his offending, there was his crime; earning for him not only a felon’s death, but the loss of character, and the branding for all time with the contemptuous title ” Demagogue.”

Yet in the slow building up of English liberties William Fitz Osbert played his part, and laid down his life in the age-long struggle for freedom, as many a better has done.

But it is equally well true that William had become dangerous for the French-speaking lords and priests and for the wealthier citizens of London. They couldn’t accept the challenge of William and his supporters to their rule and privileges; he had to be silenced. He was certainly a ‘dangerous demagogue’ to them.

Perhaps Alfred Marks, the historian of Tyburn, best sums it up:

What was he, unscrupulous demagogue or martyr in the cause of the poor? Each view was held by his contemporaries. He seems to have behaved very badly to his elder brother, whose care for him during his youth he repaid by bringing against him a charge of treason. On the other hand, it is clear that Longbeard’s enemies had against him a case which it was necessary to strengthen by baseless accusations. He was charged with blaspheming the Virgin Mary, and with taking his concubine into Bow Church. The last charge seems disproved by the circumstances in which Longbeard fled to the church for refuge. It was also set about that he was put to death for “heresy and cursed doctrine,” whereas it is obvious that his offence was political.

Postscript: What became of Archbishop Walter?

Although archbishop Walter had been able, to use Palgrave’s words, to ‘chase away the votaries of Fitz Osbert, and to reduce the citizens to obedience,’ the monks of Holy Trinity at Canterbury, to which the church at St. Mary le Bow belonged, were appalled that their archbishop had ‘had committed against the privileges of the sanctuary’ and subjected it to violence. They were, says Hoveden, therefore ‘unable to hold communication with him on any matter in a peaceable manner’, which ‘ultimately occasioned the loss of the great secular office which he held’.

As Joseph Clayton tells it:

In 1198, two years after the death of Longbeard, Hubert was compelled to resign the justiciarship. His monks at Canterbury, to whom the Church of St. Mary, in Cheapside, belonged, and who had no love for their archbishop, indignant at the violation of sanctuary and the burning of their church, appealed to the king and to the pope, Innocent III, to make Hubert give up his political activities and confine himself to the work of an archbishop. In the same year, a great council of the nation, led by St. Hugh of Lincoln, flatly refused a royal demand for money made by Hubert.

Innocent III was against him, the great barons were against him, and Hubert resigned. But he held the archbishopric till 1205.

Sources:

Roger of Wendover’s Flowers of history, Comprising the history of England from the descent of the Saxons to A.D. 1235; formerly ascribed to Matthew Paris. ed., J. A Giles (1849); Matthew Paris, Latin Chroniclers from the Eleventh to the Thirteenth Centuries, The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21); F. Palgrave, ed., Rotuli curiae regis: rolls and records of the court held before the king’s justiciars or justices, (1835); Alfred Marks, Tyburn Tree, Its History and Annals (1908); Derek Keene, William fitz Osbert (d. 1196), populist leader, Oxford Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; J. H. Round, William Fitzosbert, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1889);. William Stubbs, Constitutional History of England (1874–78); Alan Cooper, William Longbeard and the Crisis of Angevin England (2013); Charles Dickens, A Child’s History of England (1852); John McEwan, William FitzOsbert and the crisis of 1196 in London (2004); Joseph Clayton, Leaders of the people; studies in democracy (1910); John Gillingham, Roger of Howden on Crusade, in Richard Cœur de Lion: Kingship, Chivalry and War in the Twelfth Century (1994); John Gillingham, Richard 1 (1999); Thomas Allen, History and Antiquities of London (1827); G. W. S. Barrow, The bearded revolutionary, History Today (1969); Alan V. Murray, Participants in the third crusade, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, OUP; Robert Fabyan, The New Chronicle of England and France (1516), ed., Henry Ellis (1811); R. Holinshed, Of a conspiracy made in London by one William, and how he paid the penalty of his audacity, In Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1577); R. Howlett, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 2, Rolls Series, 82 (1885); Chronica magistri Rogeri de Hovedene, ed. W. Stubbs, 4 vols., Rolls Series, 51 (1868–71); Radulfi de Diceto … opera historica, ed. W. Stubbs, 2: 1180–1202, Rolls Series, 68 (1876); The historical works of Gervase of Canterbury, ed. W. Stubbs; The chronicle of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, Rolls Series, 73 (1879); W. Stubbs, ed., Gesta regis Henrici secundi Benedicti abbatis: the chronicle of the reigns of Henry II and Richard I, AD 1169–1192, Rolls Series, (1867).

Of course there was a need for some sort of communication between the conquerors and the conquered. The native English needed to know some French if they had to serve and appease their new lords in their manors, work on the lords’ home farms or understand the lawyers and judges in the courts. Slowly but surely Old English or Anglo-Saxon evolved and morphed into Middle English, the language of Chaucer. Although French remained the principal language of the rulers, one by one, and at first very reluctantly, they started to be able to understand and then speak Middle English as well.

Of course there was a need for some sort of communication between the conquerors and the conquered. The native English needed to know some French if they had to serve and appease their new lords in their manors, work on the lords’ home farms or understand the lawyers and judges in the courts. Slowly but surely Old English or Anglo-Saxon evolved and morphed into Middle English, the language of Chaucer. Although French remained the principal language of the rulers, one by one, and at first very reluctantly, they started to be able to understand and then speak Middle English as well.

In ‘The Norman Conquest’, which I believe is the most balanced and thorough recent work on the Conquest, Marc Morris summed up the extent of the dispossession:

In ‘The Norman Conquest’, which I believe is the most balanced and thorough recent work on the Conquest, Marc Morris summed up the extent of the dispossession:

Nevertheless, Uhtraed or Uchtred does look like a Northumbrian English name. Other clearly English names, whether Mercian or Northumbrian, are Æthelmund, Almaer, Wulfbert, Wynstan and Godgifu (the only named woman). We also find the Scandinavian names Beornwulf, Stenulf, Aski and Ketil. The ethnicity of the remaining names Dot, Lyfing and Teos is less clear. But we find a Dot holding large estates in Cheshire, so he might have been Mercian English too.

Nevertheless, Uhtraed or Uchtred does look like a Northumbrian English name. Other clearly English names, whether Mercian or Northumbrian, are Æthelmund, Almaer, Wulfbert, Wynstan and Godgifu (the only named woman). We also find the Scandinavian names Beornwulf, Stenulf, Aski and Ketil. The ethnicity of the remaining names Dot, Lyfing and Teos is less clear. But we find a Dot holding large estates in Cheshire, so he might have been Mercian English too.

Perhaps we should leave the last word with Orderic. Remember this was a man born in Shropshire whose father was a loyal clerical servant of Roger de Montgomery, one of Duke William’s most powerful followers and one of the most powerful men in post-Conquest England. He was also a man who went to Normandy in 1085 to become a monk at the Norman monastery of St. Evroult, and knew many of the Normans involved in the Conquest and their sons.

Perhaps we should leave the last word with Orderic. Remember this was a man born in Shropshire whose father was a loyal clerical servant of Roger de Montgomery, one of Duke William’s most powerful followers and one of the most powerful men in post-Conquest England. He was also a man who went to Normandy in 1085 to become a monk at the Norman monastery of St. Evroult, and knew many of the Normans involved in the Conquest and their sons.