It is a well-known fact that Cumbria was heavily settled by the Norsemen in the tenth century, perhaps less known is that this settlement also included Lancashire and the Wirral peninsula in Cheshire. There are almost no written sources for this Scandinavian settlement, although we can reconstruct its outlines from the meagre sources we have when they are coupled with place name evidence and archaeology. I will do this more extensively at a later date. For now I’d simply like to present a story found in the Irish Fragmentary Annals telling the events of the year A.D. 902[1] when Norse-Irish Vikings first appeared on the Wirral and later tried to take the city of Chester.

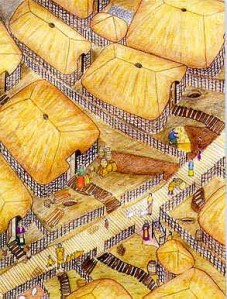

Viking houses in Dublin

First Norwegians and then Danes had settled in Ireland in the second half of the ninth century, although they had been raiding Ireland and the British Isles since the end of the eighth century. The Northmen fought each other and the native Irish. In 902 the Irish seem to have settled their own squabbles for a while and gained a temporary ascendancy and the Vikings were expelled from their Dublin base. The Annals of Ulster report for 902:

The heathens were driven from Ireland, that is from the longphort of Ath Cliath (Dublin), by Mael Finnia son of Flannacan with the men of Brega and by Cerball son of Muirecan with the Leinster men.

They were familiar with the coasts of Wales, having raided there on numerous occasions. Anglesey (called the isle of Môn by the British) attracted them as a place to settle as it was not only ‘the home of the monastic establishments of Penmon, Ynys Seirol and Caer Gybi’, but also, as Gerald of Wales later wrote:

Just as, for instance, Mount Snowdon could produce pasture for all the herds of Wales , thus the isle of Mona is so fertile in wheat and meadows to be able to supply produce for some time for the whole of Wales.

Sicut enim montes Ereri cunctis Walliae fertur totius armentis in unum coactis ad pascua, sic insula Moniae triticei graminis fertilitate toti Walliae fertur aliquamdiu sufficere posse.

Vikings Arrive by Chris Collingwood

The Northmen, referred to as Dub Gint or black pagans, under the command of Igmunt (Ingimundr), ‘came to Mona and fought the battle of Ros Melion’, now Penros, near Holyhead. But, as we will see, ‘the Britons assembled against them, and gave them hard and strong battle, and they were driven by force out of British territory’. They then sailed along to northern coast of Wales and landed on the Wirral peninsula, which was under the suzerainty of the ‘English’. Here I will let the Annals of Ireland tell the story:[2]

We have related above, that is, in the fourth year previously, that the Norwegian armies were driven out of Ireland, thanks to the fasting and prayers of the holy man, Céle Dabaill,[3] for he was a saintly and pious man, and he had great zeal for the Christians; and besides inciting the warriors of Ireland against the pagans, he laboured himself through fasting and prayer, and he strove for freedom for the churches of Ireland, and he strengthened the men of Ireland by his laborious service to the Lord; and he removed the anger of the Lord from them. For it was on account of the Lord’s anger against them that the foreigners were brought to destroy them (i.e., the Norwegians and Danes), to plunder Ireland, both church and tribe.

Now the Norwegians left Ireland, as we said, and their leader was Ingimund, and they went then to the island of Britain. The son of Cadell son of Rhodri was king of the Britons at that time. The Britons assembled against them, and gave them hard and strong battle, and they were driven by force out of British territory.

After that Ingimund with his troops came to Aethelflaed[4], Queen of the Saxons; for her husband, Aethelred, was sick at that time. (Let no one reproach me, though I have related the death of Aethelred above, because this was prior to Aethelred’s death and it was of this very sickness that Aethelred died, but I did not wish to leave unwritten what the Norwegians did after leaving Ireland.) Now Ingimund was asking the Queen for lands in which he would settle, and on which he would build barns and dwellings, for he was tired of war at that time. Aethelflaed gave him lands near Chester, and he stayed there for a time.[5]

What resulted was that when he saw the wealthy city, and the choice lands around it, he yearned to possess them. Ingimund came then to the chieftains of the Norwegians and Danes; he was complaining bitterly before them, and said that they were not well off unless they had good lands, and that they all ought to go and seize Chester and possess it with its wealth and lands. From that there resulted many great battles and wars. What he said was, ‘Let us entreat and implore them ourselves first, and if we do not get them good lands willingly like that, let us fight for them by force.’ All the chieftains of the Norwegians and Danes consented to that.

Ingimund returned home after that, having arranged for a hosting to follow him. Although they held that council secretly, the Queen learned of it. The Queen then gathered a large army about her from the adjoining regions, and filled the city of Chester with her troops.

A Norse Dublin ship

Almost at the same time the men of Foirtriu[6] and the Norwegians fought a battle. The men of Alba fought this battle steadfastly, moreover, because Colum Cille was assisting them, for they had prayed fervently to him, since he was their apostle, and it was through him that they received faith. For on another occasion, when Imar Conung[7] was a young lad and he came to plunder Alba with three large troops, the men of Alba, lay and clergy alike, fasted and prayed to God and Colum Cille until morning, and beseeched the Lord, and gave profuse alms of food and clothing to the churches and to the poor, and received the Body of the Lord from the hands of their priests, and promised to do every good thing as their clergy would best urge them, and that their battle-standard in the van of every battle would be the Crozier of Colum Cille—and it is on that account that it is called the Cathbuaid ‘Battle-Triumph’ from then onwards; and the name is fitting, for they have often won victory in battle with it, as they did at that time, relying on Colum Cille. They acted the same way on this occasion. Then this battle was fought hard and fiercely; the men of Alba won victory and triumph, and many of the Norwegians were killed after their defeat, and their king was killed there, namely Oittir son of Iarngna. For a long time after that neither the Danes nor the Norwegians attacked them, and they enjoyed peace and tranquillity. But let us turn to the story that we began.

The armies of the Danes and the Norwegians mustered to attack Chester, and since they did not get their terms accepted through request or entreaty, they proclaimed battle on a certain day. They came to attack the city on that day, and there was a great army with many freemen in the city to meet them. When the troops who were in the city saw, from the city wall, the many hosts of the Danes and Norwegians coming to attack them, they sent messengers to the King of the Saxons, who was sick and on the verge of death at that time, to ask his advice and the advice of the Queen. What he advised was that they do battle outside, near the city, with the gate of the city open, and that they choose a troop of horsemen to be concealed on the inside; and those of the people of the city who would be strongest in battle should flee back into the city as if defeated, and when most of the army of the Norwegians had come in through the gate of the city, the troop that was in hiding beyond should close the gate after that horde, and without pretending any more they should attack the throng that had come into the city and kill them all.

The Romans building Chester’s walls

Everything was done accordingly, and the Danes and Norwegians were frightfully slaughtered in that way. Great as that massacre was, however, the Norwegians did not abandon the city, for they were hard and savage; but they all said that they would make many hurdles, and place props under them, and that they would make a hole in the wall underneath them. This was not delayed; the hurdles were made, and the hosts were under them making a hole in the wall, because they wanted to take the city, and avenge their people.

It was then that the King (who was on the verge of death) and the Queen sent messengers to the Irish who were among the pagans (for the pagans had many Irish fosterlings), to say to the Irishmen, ‘Life and health to you from the King of the Saxons, who is ill, and from the Queen, who holds all authority over the Saxons, and they are certain that you are true and trustworthy friends to them. Therefore you should take their side: for they have given no greater honour to any Saxon warrior or cleric than they have given to each warrior or cleric who has come to them from Ireland, for this inimical race of pagans is equally hostile to you also. You must, then, since you are faithful friends, help them on this occasion.’ This was the same as saying to them, ‘Since we have come from faithful friends of yours to converse with you, you should ask the Danes what gifts in lands and property they would give to the people who would betray the city to them. If they will make terms for that, bring them to swear an oath in a place where it would be convenient to kill them, and when they are taking the oath on their swords and their shields, as is their custom, they will put aside all their good shooting weapons.’

Irish fight the Vikings

All was done accordingly, and they set aside their arms. And the reason why those Irish acted against the Danes was because they were less friends to them than the Norwegians. Then many of them were killed in that way, for huge rocks and beams were hurled onto their heads. Another great number were killed by spears and by arrows, and by every means of killing men.

However, the other army, the Norwegians, was under the hurdles, making a hole in the wall. What the Saxons and the Irish who were among them did was to hurl down huge boulders, so that they crushed the hurdles on their heads. What they did to prevent that was to put great columns under the hurdles. What the Saxons did was to put the ale and water they found in the town into the towns cauldrons, and to boil it and throw it over the people who were under the hurdles, so that their skin peeled off them. The Norwegians response to that was to spread hides on top of the hurdles. The Saxons then scattered all the beehives there were in the town on top of the besiegers, which prevented them from moving their feet and hands because of the number of bees stinging them. After that they gave up the city, and left it. Not long afterwards there was fighting again …

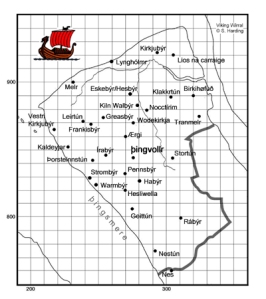

Viking Wirral

The Norsemen withdrew to the Wirral and settled there. Over the years to come, they and other Scandinavian compatriots from Ireland and Scotland, as well as some coming direct from Scandinavia, went on to settle in western Lancashire, on the isle of Man and in Cumbria. I will tell more of that in forthcoming articles, but 902 was the first time the Vikings came to settle in North West England.[8]

Notes:

[1] Probably 902 and 903. The attack on Chester we know from Anglo-Saxon sources took place in circa 907.

[2] I use the more modern translation and edition: Joan N. Radner (ed. & trans.) Fragmentary annals of Ireland (Dublin 1978).

[3] Abbot of Bangor

[4] Aethelflaed, the ‘Lady of the Mercians’, was King Alfred of Wessex’s eldest daughter and husband of Ealdorman Aethelred of Mercia.

[5] The Wirral peninsula.

[6] Land of the Pictish-Gaels

[7] Viking King Ívarr. Some suggest he was Ivar the Boneless.

[8] It is unlikely that Carlisle was destroyed by the Danish warlord Halfdan in 875 as many suggest.