North Meols is an ancient parish on the coast of south-west Lancashire. Much of it has now been gobbled up by the modern resort town of Southport. Like most of this stretch of coast ‘between the Mersey and the Ribble’, as it was referred to in William the Conqueror’s Domesday survey in 1086, it was heavily settled by the Scandinavians in the tenth century after their temporary expulsion from Dublin. The name Meols itself derives from the Old Norse word melr, meaning sand hills or dunes, an apt description for the area. I want to use the example of North Meols to tell just a little of the generally unrecorded and under-appreciated Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire.

North Meols Mudflats

There are almost no written sources mentioning Lancashire before William the Conqueror’s Domesday survey of 1086 – even then it was not called Lancashire but was still included under Yorkshire. The area of coast where North Meols lies was referred to as ‘between the Mersey and the Ribble’.[1] This stretch of coast was inhospitable and remote. For a long time it was not a very sought-after place to live. In his excellent local history of North Meols and Southport, Peter Aughton tells something about the geography of the area. It is such a fine evocative description that I will quote it in full:[2]

‘The whole of the coastal plain was dotted with shallow meres which were destined to acquire names like Gattern Mere, Barton Mere, White Otter and Black Otter Pool, but the greatest of these was Martin Mere. It measured over four miles from east to west and three miles from north to south, and at one point it came within a mile of the sea. In its time Martin mere was numbered amongst the greatest meres in England. Great flocks of wild geese flew over the waters. Pike, perch and bream swam beneath the surface and the osprey nested in the rushes of its hinterland. The waters would rise and fall with the seasons and after heavy rains the acres of bog and marshland were reclaimed by the waters, dried up creeks filled with water and became part of the mere until the next dry spell. After particularly heavy rains Martin Mere would sometimes manage to find an outlet to the coast and spill over into the great salt waters of the sea.

North of the mere was a river estuary, another habitat of geese and wild fowl, a land of mudflats, salt marshes and sea-washed – but to the south the coastal regions were of an entirely different nature. Here blown sand accumulated into a wide band of desolate sand hills with ever changing contours sculpted by the wind. Here the land was in perpetual conflict with the sea. On the slopes of the sand hills sparse clumps of marram grass struggled for a hold on the sandy inclines but in the valleys between the dunes the sand in some places gave way to carpets of local vegetation where, at the lowest points, lay dark shallow pools of water. Here grew the marsh marigold, reedmace, burr reed, water mint and bog bean. Millions of years of evolution had produced the sand lizard which scurried through the coarse grass, and in the spring could be heard the croaking, unlovely mating call of the natterjack toad.’

A better evocation of ‘place’ I have yet to read. It was the place where I was born and where I spent the early years of my life on its cold and windswept sands, although its rough natural beauty had by then been much altered by Man, not always for the better.

But, as Aughton rightly says, despite the fact that ‘between the sand dunes, the mud flats, and the mere, nature had created a stretch of fertile soil with woodlands for fuel, pasture for animals, and fresh water only a few feet below the ground’, the native British of this island, and later on the Northumbrian English, had pretty much ignored it, having so many other more fertile areas to chose from. When the Scandinavians arrived here in the tenth century they would have found an almost untouched land. If there were any people living here they were without doubt few and far between.

King Athelstan

Before the Scandinavians arrived what is now called Lancashire had nominally been a part of the kingdom of Northumbria, whose south-western boundary was the River Mersey. But as far as we can tell the Northumbrian English had never settled the desolate coast around North Meols, and the topographical place name evidence suggests that Celtic British settlement of the area was at most sparse.[3] Any English influence from Mercia or Wessex in ‘Lancashire’ only came later too, following the ‘submission’ of the Scots, Cumbrians and Norse to King Edward the Elder in 920 at Bakewell in Derbyshire and in 927 to King Athelstan at Eamont Bridge (or Dacre) in Cumberland.

The Scandinavians had started to raid and then settle in Ireland in the first half of the ninth century.[4] They established bases and trading centres, called longphorts, in Dublin, Waterford, Cork and elsewhere. But in the year 902 the Irish, who often fought each other as much as they did the Vikings, managed for a short time to unite enough to expel the Scandinavians from Dublin. The Annals of Ulster reported:

The heathens were driven from Ireland, that is from the longphort of Ath Cliath (Dublin), by Mael Finnia son of Flannacan with the men of Brega and by Cerball son of Muirecan with the Leinster men… and they abandoned a good number of their ships, and escaped half dead after they had been wounded and broken.[5]

These expelled ‘Hiberno-Norse’ fled to the nearby coasts of Wales and north-west Britain. At least one group first went to Anglesey in Wales. The Annals of Wales for 902 say:[6]

Igmund came to Mona and took Maes Osfeilion.

Igmunt in insula Mon venit tenuit Maes Osmeliaun

Norse fleet

The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland tell the story in more detail. It seems that the British Welsh repulsed the Northmen in Anglesey, after which the Scandinavians then settled ‘near Chester’, in what is now Cheshire, with the consent of Aethelflaed, the ‘Lady of the Mercians’.

Now the Norwegians left Ireland, as we said, and their leader was Ingimund, and they went then to the island of Britain. The son of Cadell son of Rhodri was king of the Britons at that time. The Britons assembled against them, and gave them hard and strong battle, and they were driven by force out of British territory.

After that Ingimund with his troops came to Aethelflaed, Queen of the Saxons; for her husband, Aethelred, was sick at that time. (Let no one reproach me, though I have related the death of Aethelred above, because this was prior to Aethelred’s death and it was of this very sickness that Aethelred died, but I did not wish to leave unwritten what the Norwegians did after leaving Ireland.) Now Ingimund was asking the Queen for lands in which he would settle, and on which he would build barns and dwellings, for he was tired of war at that time. Aethelflaed gave him lands near Chester, and he stayed there for a time.[7]

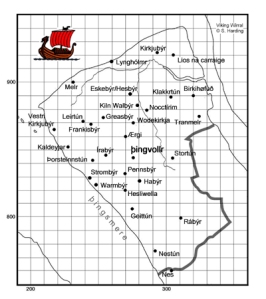

Viking Wirral

But the Scandinavians under Ingimund weren’t content with what the Mercian Aethelflaed had given them, they saw the ‘wealthy city’ of Chester ‘and the choice lands around it’ and Ingimund ‘yearned to possess them’. Probably in 910, he collected the ‘chieftains of the Norwegians and Danes’ who had come with him from Ireland and attacked Chester, only to be bloodily repulsed by the Mercians who had just restored the city’s walls and garrisoned the town.[8]

The Vikings then settled down peacefully on the Wirral which became thoroughly Scandinavian.[9]

It was at this time in the early tenth century that the Scandinavians from Ireland probably also first settled along the Lancashire coast. Perhaps some of them were even the ‘chieftains of the Norwegians and Danes’ referred to as combining with Ingimund to besiege the English at Chester?

Cuerdale Hoard

So let us return to Lancashire. In 1840 some workmen discovered a truly immense hoard of Viking silver at Cuerdale on the River Ribble near Preston.[10] Cuerdale is of course itself a Norse name. This hoard is conventionally dated to between 905 and 910. It could well have been a Viking leader’s war chest brought to finance his attempt to recapture Dublin, possibly in league with the Scandinavians of York.[11] How and why this Viking leader left such a large amount of treasure buried on the banks of the River Ribble is not known. The dating of the burial is controversial and relies upon dating the thousands of coins it contained. Although it is not the academic consensus, it is certainly possible that the hoard was buried later than 905-910, perhaps even as late as 937 when the Northmen, in league with the Scots and Strathclyde British (the ‘Cumbrians’), were defeated by the English king Athelstan at the famous Battle of Brunanburh.[12] The River Ribble itself was certainly a place the Vikings made use of. It was a natural point of arrival and departure for them from Ireland, and the Ribble was certainly on the most direct route joining the Irish Sea with York.

Whether the Cuerdale hoard was buried in the years after 905 or a couple of decades later the evidence suggests that it was during this period that the stretch of coast between the Mersey and the Ribble was first settled by Scandinavians who gave their names to so much of the area.

In North Meols and along the nearby River Ribble and its tributary the River Douglas the Vikings would have found many convenient places to ground their ships. As suggested, the area was either not inhabited or only sparsely so. In the records we find not one mention of any confrontation between these Scandinavians and any resident peoples. This implies that the settlement was fairly peaceable. The great historian of English place names, Eilert Ekwall, suggested that this is ‘only a hypothesis’ because it is an argument ‘from silence’, meaning that this view comes only from the fact that there are no written records of clashes between Scandinavian settlers and native inhabitants.[13] Frederick Wainwright, by far the greatest historian of the Scandinavian settlement of north-west England, wrote that the evidence for the peaceable nature of the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire ‘is none the less powerful… since it is almost inconceivable that an organized military conquest or a violent social upheaval, even in the remote north-west, should altogether escape the notice of both contemporary and later annalists’. Wainwright added:

In North Meols and along the nearby River Ribble and its tributary the River Douglas the Vikings would have found many convenient places to ground their ships. As suggested, the area was either not inhabited or only sparsely so. In the records we find not one mention of any confrontation between these Scandinavians and any resident peoples. This implies that the settlement was fairly peaceable. The great historian of English place names, Eilert Ekwall, suggested that this is ‘only a hypothesis’ because it is an argument ‘from silence’, meaning that this view comes only from the fact that there are no written records of clashes between Scandinavian settlers and native inhabitants.[13] Frederick Wainwright, by far the greatest historian of the Scandinavian settlement of north-west England, wrote that the evidence for the peaceable nature of the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire ‘is none the less powerful… since it is almost inconceivable that an organized military conquest or a violent social upheaval, even in the remote north-west, should altogether escape the notice of both contemporary and later annalists’. Wainwright added:

To this may be added the positive if somewhat inconclusive evidence of place-names. It has been shown… that the distribution of Scandinavian place-names in south Lancashire suggests very strongly that the Norsemen were willing to occupy the poorer lands along the coast, lands which the earlier English settlers had deliberately avoided. If this is correct then the settlement can hardly have been preceded by a military conquest, for the conquerors would not choose to live in neglected marshlands… There is no reason to believe that the relations were cordial, but there is equally no reason, at least from the evidence of place-names, to suspect any violent hostility.[14]

As in Cumbria further north, between the Mersey and the Ribble we find Scandinavian place names everywhere. In the immediate vicinity of North Meols itself we find Crossens, Birkdale, Ainsdale, Formby, Altcar, Crosby, Litherland and Kirkdale. Inland we find Scarisbrick, Tarlscough, Tarleton, Ormskirk, Kellamerg and Hesketh. These are all Norse names. The same is true up and down the coast.[15] If we were to add in lesser names of fields and topographical features the list would be almost endless.

As in Cumbria further north, between the Mersey and the Ribble we find Scandinavian place names everywhere. In the immediate vicinity of North Meols itself we find Crossens, Birkdale, Ainsdale, Formby, Altcar, Crosby, Litherland and Kirkdale. Inland we find Scarisbrick, Tarlscough, Tarleton, Ormskirk, Kellamerg and Hesketh. These are all Norse names. The same is true up and down the coast.[15] If we were to add in lesser names of fields and topographical features the list would be almost endless.

Recent DNA studies of the Scandinavian ancestry of people in Cheshire and south-west Lancashire have concluded that about half of the people bearing historically old family names there are descendants of these Vikings settlers – who without much doubt came from Ireland.

These Scandinavian settlers soon turned to fishing and farming and away from typical or stereotypical Viking raiding. Nevertheless, as the tenth century progressed, it is hard to imagine that at least some of these Lancastrian Scandinavians didn’t occasionally participate in the many battles fought between the Norse, English, British and Scots for the ultimate control of north-west England.

And so life Scandinavian continued In North Meols: farming, fishing and maybe a bit of fighting too.

And then after the Norman Conquest this simple life was shattered. The Norman French didn’t immediately arrive in Lancashire after 1066. When the French first ventured north to commit ethnic genocide in Yorkshire and other northern areas in 1069, in the rather misnamed ‘Harrying of the North’, they probably also laid waste to some parts of Lancashire and Cheshire too.[16] But they probably never set foot in North Meols.

Roger de Poitou

In 1086, when the Domesday survey of England was ordered by William the Conqueror, North Meols, plus nearly the whole of modern Lancashire (and much else besides), had been given to Roger de Poitou (the son of William’s friend and supporter Roger de Montgomerie) as part of William’s divvying up of the whole of his conquered country among his followers.[17]

Domesday Book records that five unnamed thegns, most likely descendants of the Scandinavian settlers in the early tenth century, though no doubt by now mixed with English and, perhaps, British blood, had held Ortringmele (North Meols), Herleshala (Hasall) and Hireton (Hurleton) before the Conquest. Now these lands were part of Roger de Poitou’s huge holdings, and he had granted the liberty and ‘farm’ of them (by ‘subinfeudation’) to various of his French vassals, called Geoffrey, Roger, William, Robert, Gilbert and Warin.[18] This is another story; the story of a brutal, centuries-long Norman-French suppression and exploitation of Lancashire and of all of England. It’s not a happy history. See: Ravening Wolves – The French hostile take-over of Lancashire

A number of eminent Victorian and Edwardian historians and antiquarians had much to say about the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire. Much is this still of interest, though much is just fantasy. Here is one of my favourite quotes from S. W. Partington’s The Danes in Lancashire:

From the Mersey to the Ribble was a long, swampy, boggy plain, and was not worth the Romans’ while to make roads or to fix stations or tenements. From the Conquest until the beginning of the 18th century this district was almost stagnant, and its surface undisturbed. The Dane kept to the shore, the sea was his farm. He dredged the coast and estuary, with his innate love of danger, till Liverpool sprang up with the magic of Eastern fable, and turned out many a rover to visit every region of the world. The race of the Viking are, many of them, the richest merchants of the earth’s surface.[19]

I wish it were still so.

References:

[1] The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster, Vol. 1, W. Farrer and J. Brownbill, London. 1906.

[2] Peter Aughton, North Meols and Southport – A History, Lancaster, 1988, pp. 16-17.

[3] See: F. T. Wainwright, The Scandinavians in Lancashire, pp. 181- 227, in Scandinavian England, ed. H. P. R Finberg, Chichester, 1975.

[4] Clare Downham, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland – The Dynasty of Ivarr to A. D. 1014, Edinburgh, 2007.

[5] The Annals of Ulster, ed. and trans. S, Mac Airt and G. Niocaill, Dublin, 1983, p. 354.

[6] David Dumville, ed. and trans., Annales Cambriae, A.D. 682-954: Texts A-C in Parallel, Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, University of Cambridge, 2002.

[7] Joan N. Radner, ed. and trans., Fragmentary annals of Ireland, Dublin, 1978.

[8] Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in D. Whitelock, English Historical Documents, London, 1979.

[9] Stephen Harding, Viking Mersey: Scandinavian Wirral, West Lancashire and Chester, 2002.

[10] J. Graham-Campbell, The Cuerdale Hoard and Related Viking-age Silver and Gold from Britain and Ireland in the British Museum, London: British Museum Press, 2011.

[11] J. Graham-Campbell (ed.), Viking treasure from the North, Selected papers from The Vikings of the Irish Sea conference, Liverpool, 18–20 May 1990 (Liverpool, National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, 1992)

[12] For the Battle of Brunanburh see: Michael Livingston (ed.), The Battle of Brunanburh, A Casebook, Exeter, 2011.

[13] E, Ekwall. The Place Names of Lancashire, Manchester, 1922; The Concise Dictionary of English Place-Names, Oxford, 1936.

[14] F. W. Wainwright, The Scandinavians in Lancashire, p. 192.

[15] E. Ekwall, The Place Names of Lancashire; John Sephton, A Handbook of Lancashire Place Names, Liverpool, 1913; Henry Harrison, The Place Names of the Liverpool District, London, 1898; Geoffrey Leech, The unique heritage of the place-names in north-west England, Lancaster,.

[16] Marc Morris, The Norman Conquest, London, 2012; Peter Rex, 1066, A New History of the Norman Conquest, Cirencester, 2011.

[17] Ibid

[18] The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster, Vol. 1, W. Farrer and J. Brownbill, London. 1906.

[19] S. W. Partington, The Danes in Lancashire, London, 1909, pp. 7- 8.

You have the makings of a very interesting book with all these posts, perhaps organised by region.

[…] Geoffrey Leech, “The Unique Heritage of Place-Names in North West England”; Stephen Lewis, “North Meols and the Scandinavian Settlement of Lancashire“; and Stephen Lewis, “The First Scandinavian Settlers in North West […]

What a fantastically researched article – this is absolute gold for me at the moment while I’m trying to trace the history of two halves of the ‘Headless Cross’ at both Grimeford Village and the Harris Museum respectively!

I’m presently working on a 3D scanned reconstruction of the original, half of which you can see here: https://sketchfab.com/models/138c5a10404f4bbf8556c58c6b66b54a

The other half I’m actually scanning on Monday 4th September at the Harris – I’d appreciate any help in researching the history behind this amazing artefact!

Very Interesting, I recently did a Heritage DNA test and my results came back as 16% Norwegian/Danish and being a Preston/west Lancashire native it very much backs up this theory.