The history of the British colonization of ‘Brittany’ is not well known either in Britain or in France. It is a fascinating story, although the early years of the settlement in the fifth century remain obscure. Yet not long after the British Celts had fled the invading English (Saxons) in the 450s a large British army under a king called Riothamus was defeated by the Visigoths in Gaul – what is now France. This is the story I wish to tell.

Attila in Gaul, 451

I previously told the story of a Gallo-Roman aristocrat called Paulinus of Pella (see here), about his troubles caused by the arrival of the Germanic Goths in Bordeaux and his ultimately unsuccessful attempts to maintain at least a semblance of the pampered and privileged life he had been born into. At the time of his death around 460 the Western Roman Empire was in the finals stages of disintegration. Germanic tribes were busily entrenching themselves all over Roman Gaul and extending the territories they controlled: the Goths spreading out from their kingdom of Toulouse, the Franks in the North East, the Burgundians in the East with their new capital in Lyon, and even the Alans. The non-Germanic Huns under their leader Attila had also threatened, but they withdrew after having been defeated by the Roman general Aëtius and his Gothic allies at the famous Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, near Châlons, in 451. They never returned to Gaul.

By the time of Paulinus’s death the Romans and Gallo-Romans had already had to make uncomfortable accommodations with the new Germanic masters, yet the Empire was still capable of striking back, though by now more weakly and less frequently.

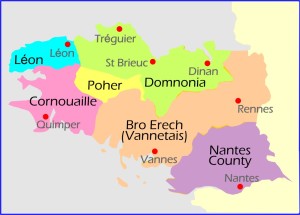

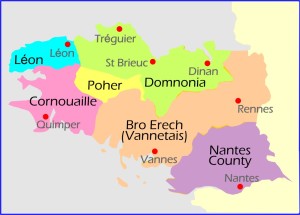

Into this caustic mix of rivalries and fights for land a new ethic group arrived in the 450s: the British. They and their descendants would settle the north-west corner of Gaul called Armorica and would ultimately give their ethnic name to this land: Brittany, or Bretagne in French.

The Britons who arrived in Gaul in the 450s are often said to have been a ‘second wave’ of refugee immigrants.[1] An earlier group of British fighters had accompanied the British imperial usurper Marcus Maximus to Gaul in 383, never to return. The eventual fate of this first wave remains unknown and is a matter of some scholarly debate. But the British of the second wave were without any doubt those who went on to ‘create’ Brittany.

Background to the emigration

The background to this emigration was the ‘Saxon Advent’, that is the arrival of the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ in Britain. This advent is conventionally dated to the year 441, but this dating is controversial.[2] The leaders of the first Saxon party were said to have been called Hengest and Horsa. Under the year 449 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports:

This year Marcian and Valentinian assumed the empire, and reigned seven winters. In their days Hengest and Horsa, invited by Wurtgern (Vortigern), king of the Britons to his assistance, landed in Britain in a place that is called Ipwinesfleet; first of all to support the Britons, but they afterwards fought against them.[3]

The British monk Gildas wrote of the subsequent sufferings of the British:

The British monk Gildas wrote of the subsequent sufferings of the British:

Some, therefore, of the miserable remnant (of the British), being taken in the mountains, were murdered in great numbers; others, constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves for ever to their foes, running the risk of being instantly slain, which truly was the greatest favour that could be offered them: some others passed beyond the seas with loud lamentations instead of the voice of exhortation. “Thou hast given us as sheep to be slaughtered, and among the Gentiles hast thou dispersed us.” Others, committing the safeguard of their lives, which were in continual jeopardy, to the mountains, precipices, thickly wooded forests, and to the rocks of the seas (albeit with trembling hearts), remained still in their country. But in the meanwhile, an opportunity happening, when these most cruel robbers were returned home, the poor remnants of our nation (to whom flocked from divers places round about our miserable countrymen as fast as bees to their hives, for fear of an ensuing storm), being strengthened by God, calling upon him with all their hearts, as the poet says, “With their unnumbered vows they burden heaven,” that they might not be brought to utter destruction, took arms under the conduct of Ambrosius Aurelianus, a modest man, who of all the Roman nation was then alone in the confusion of this troubled period by chance left alive. His parents, who for their merit were adorned with the purple, had been slain in these same broils, and now his progeny in these our days, although shamefully degenerated from the worthiness of their ancestors, provoke to battle their cruel conquerors, and by the goodness of our Lord obtain the victory.[4]

British Brittany

The others who ‘passed beyond the seas with loud lamentations’ went to Armorica in Gaul, which would later be called Brittany after them.

There is much to tell about the circumstances, timing and composition of this British emigration to Armorica, particularly whether it was a coordinated mass emigration under powerful Romano-British leaders or whether it was a more piecemeal process involving many smaller, disparate groups of frightened refugees. Whatever the case, by 461, only twenty years after the conventional date of the Saxon Advent, there were already enough Britons in Armorica to justify them sending their own bishop to the Council of Tours. T. M. Charles Edwards writes:

The first strong evidence for the emergence of a distinct British settlement in the north-west of Armorica does not come until 461, when subscriptions to the council of Tours (AD 461) included ‘Mansuetus, bishop of the Britons’.[5]

Most of what we know about these and subsequent early British refugees in Gaul comes from the many ‘lives’ of Celtic saints and is best left to the specialists in such matters. Yet in just a few generally reliable sources we soon find mention of a British king called Riothamus whose 12,000 strong army was defeated by the Visigoths of King Euric around 469/70. Before considering, but not answering, the question of who Riothamus was, I will try to explain what happened and perhaps why and where.

Bourges and Déols

Before we hear anything of Riothamus, we find a brief mention in Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks of an event which probably took place sometime between 463 and 468. It says:

The Britanni were driven from Bourges by the Goths, and many were slain at the village of Déols.[6]

Brittani de Bitoricas a Gothis expulsi sunt, multis apud Dolensem vicum peremptis.

Deols in Berry

Following the mention of a British bishop at the Council of Tours in 461, this is the next time where explicit reference is made to any British (‘Britanni’) in Gaul. Conventionally these events at Bourges and Déols (in the county of Berry about 20 miles southwest of Bourges) where ‘many (British) were slain’ by the Goths, is dated to about 469 and equated with the defeat of Riothamus’s British army by Euric’s Visigoths. I will discuss this battle later, but here I would just like to suggest that the conflation of events at Bourges/Déols and the battle which certainly took place in 469/70 is probably mistaken.

Ralph Mathisen expresses the conventional view:

In Gaul, Anthemius was faced by the able and ambitious Visigothic king, Euric (466-484). In 469 or shortly afterward, the Armorican Bretons commanded by Riothamus… were engaged by Anthemius to oppose the Visigoths. But when, after having occupied Bourges, the Bretons attacked the Goths on their own territory at Déols, they suffered a signal defeat.[7]

How Mathisen draws the precise implication from Gregory of Tours’ words that ‘after having occupied Bourges, the Bretons attacked the Goths on their own territory at Déols’ is beyond me. Rather the text says simply but explicitly that the British ‘were driven from Bourges by the Goths, and many were slain at the village of Déols’.

The paragraph in Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks where we find mention of Britons being killed by Goths at Déols was in all likelihood taken from a ‘year chronicle’ and is thus probably roughly in chronological order.[8] If this is so then a close examination of the paragraph reveals that it covers events in the period between 463 and 467/8, with the events at Déols most likely taking place around 465/6. Here is the full paragraph:

Now Childeric fought at Orleans and Adovacrius came with the Saxons to Angers. At that time a great plague destroyed the people. Egidius died and left a son, Syagrius by name. On his death Adovacrius received hostages from Angers and other places. The Britanni were driven from Bourges by the Goths, and many were slain at the village of Déols. Count Paul with the Romans and Franks made war on the Goths and took booty. When Adovacrius came to Angers, king Childeric came on the following day, and slew count Paul, and took the city. In a great fire on that day the house of the bishop was burned. After this war was waged between the Saxons and the Romans; but the Saxons fled and left many of their people to be slain, the Romans pursuing. Their islands were captured and ravaged by the Franks, and many were slain. In the ninth month of that year, there was an earthquake.

Most of these events mentioned by Gregory can be confirmed and cross-checked from other sources. Importantly they seem to have taken place in the order mentioned by Gregory. The earliest events, such as Childeric at Orleans and a plague, can be dated to 463/4. In the middle we read that ‘Euric, the king of the Visigoths, observing the frequent changes of the Roman princes, attempted to seize the Gauls for his own’. Euric became king in 466. The last sentence concerning an earthquake can be dated to 467/8. Hydatius wrote that ‘in the second year of the emperor Anthemius blood burst forth from the ground in the middle of Toulouse and continued to flow for an entire day’, and Anthemius became Emperor in 467. As historian Penny MacGeorge comments about the period:

Most of these events mentioned by Gregory can be confirmed and cross-checked from other sources. Importantly they seem to have taken place in the order mentioned by Gregory. The earliest events, such as Childeric at Orleans and a plague, can be dated to 463/4. In the middle we read that ‘Euric, the king of the Visigoths, observing the frequent changes of the Roman princes, attempted to seize the Gauls for his own’. Euric became king in 466. The last sentence concerning an earthquake can be dated to 467/8. Hydatius wrote that ‘in the second year of the emperor Anthemius blood burst forth from the ground in the middle of Toulouse and continued to flow for an entire day’, and Anthemius became Emperor in 467. As historian Penny MacGeorge comments about the period:

Marcellinus comes noted an earthquake in the Ravenna region and an eruption of Vesuvius; and the Fasti Vindobonenses an outbreak of cattle disease in AD 467. There was pestilence in Italy, particularly in Campania. In both East and West this was a time of disasters and unusual events including: the fire in Constantinople in AD 465; earthquakes and floods in the eastern Mediterranean; celestial phenomena in AD 467; and famines. All this may have contributed to a general feeling of insecurity, even of doom.[9]

On the basis of all this chronology it is likely that the killing of the British at Déols took place around 465/6, and was separate from the battle lost by Riothamus’s British army, which can be dated with some certainty to 469/70.

If this is correct, then the events at Déols probably had nothing to do with Riothamus or, even if he had been a British leader at Bourges and Déols, it wasn’t the great battle where he and his British army were defeated by Euric. The scanty available evidence regarding the early settlement of ‘Brittany’ suggests that it was heaviest in the north-west of Armorica peninsula but that some groups of Britons had ventured further south along the coast to the vicinity of Vannes and Nantes. Bourges is situated far inland and what the British were doing there is a bit of a mystery. It might well have been that some British refugees had established themselves in the former Roman town of Bourges and, having been driven out by the Goths, were then killed (or at least some of them) at Déols as they fled back towards the coast.

Whatever the case, we can now turn to the defeat of Riothamus and his substantial British army by Euric’s Goths in about 469/70.

The British defeat

Our information comes from Jordanes’ The Origins and Deeds of the Goths. Jordanes was a Gothic Roman bureaucrat in the mid sixth century. Writing about the years 466 – 476 he says:

Euric, the king of the Visigoths, observing the frequent changes of the Roman princes, attempted to seize the Gauls for his own. Anthemius, the Emperor, receiving intelligence of this, immediately invited the aid of the Britons, whose King Riothimus, coming with twelve thousand by way of Ocean, and disembarking from his ships, was received into the city/state of the Bituriges. Euric, king of the Visigoths, came against them leading an innumerable army, and fighting for a long time, overcame Riothimus, the king of the Britons, before the Romans had joined company with him. Having lost a great part of his army, he fled with all whom he could save, and came to the neighbouring nation of the Burgundians, then confederate with the Romans. But Euric, king of the Visigoths, seized Auvergne, a city of Gaul…. When Euric, as we have already said, beheld these great and various changes, he seized the city of Arverna, where the Roman general Ecdicius was at that time in command. He was a senator of most renowned family and the son of Avitus, a recent emperor who had usurped the reign for a few days–for Avitus held the rule for a few days before Olybrius, and then withdrew of his own accord to Placentia, where he was ordained bishop. His son Ecdicius strove for a long time with the Visigoths, but had not the power to prevail. So he left the country and (what was more important) the city of Arverna to the enemy and betook himself to safer regions.[10]

Emperor Anthemius

The context of this battle between Britons and Visigoths was that in early 467 a ‘Greek’ called Anthemius had been elevated to be Roman Emperor. He wasn’t very popular among the Gallo-Ronan aristocracy but he did try to protect Gaul. Anthemius had sought the help of the British, as Jordanes tells us. Most likely he offered them ‘federate’ status and the prospect of land, as the Romans of the late empire often did when dealing with ‘barbarian’ tribes. At this date the main concern of the Romans and Gallo-Romans was King Euric’s Goths. Initially these Visigoths (i.e. western Goths) had been granted their territory in 418 centred on Toulouse. For many years they acted as unruly and not always obedient allies of the Romans. But in 466 Euric had succeeded to the Gothic throne by murdering his brother Theoderic and broke with Rome. The Goths already controlled much of south-west Gaul and had started to push northwards. One of their key objectives was the region of Auvergne with its principal city of Arverna (now Clermont-Ferrand). It was to stem this Gothic advance that Anthemius had requested the assistance of the British, who, as Jordanes says, came ‘with twelve thousand by way of Ocean’ and disembarked from their ships.

Where the British ships actually arrived, as well as from where they came, is not known. ‘Ocean’ then and now is the Atlantic seaboard of western France. It is because Jordanes says that the British were received into the city/state of ‘the Bituriges’ that conventionally Riothamus’s battle is placed at Bourges because ‘Bituriges’ is usually translated as Bourges. But this identification while possible is by no means certain. The Gallic Bituriges people were settled all over Aquitaine, although according to the Roman Strabo their territory was surrounded by that of a distinct Aquitanian people, and the Bituriges ‘were not themselves Aquitanian and took no part in their political affairs’. The Bituriges Vivisci were settled around Bordeaux and the Bituriges Cubi around Bourges. So the British landing could well have been as far south as Bordeaux, which unlike Bourges is actually on the Ocean, Bourges itself is a very long way inland. I will leave such conjectures for now; we simply don’t know here the British disembarked.

Riothamus fights the Visigoths

The link up with the Romans that didn’t happen

Jordanes says the Riothamus’s British were expecting to join forces with the Romans but that ‘before the Romans had linked up with him’ he was met and defeated by the Goths. Emperor Anthemius’s promised forces can hardly have been based in Gaul because these forces didn’t amount to much by this time. It is more likely that it was a Roman army under the command of Anthemius’s son Anthemiolus who the British were hoping to meet. The Gallic Chronicle of 511 says:

Anthemiolus was sent to Arles by his father the emperor Anthemius along with Thorisarius, Everdingus, and Hermianus the Count of the Stables. King Euric encountered them on the other side of the Rhone and, after killing the generals, devastated everything.

Antimolus a patre Anthemio imperatore cum Thorisario, Everdingo et Hermiano com. stabuli Arelate directus est, quibus rex Euricus trans Rhodanum occurrit occisisque ducibus omnia vastavit.

Visigoths

This event falls between the succession of Euric in 466 and the war between Anthemius and Ricimer (471–472). ‘It can probably be further narrowed to the period when Anthemius is known to have been organising a concerted effort to remove the Visigoths from Gaul between 468 and 471.’[11]

So it is quite possible that ‘Anthemiolus’ army was sent to reinforce Riothamus and that Euric defeated both forces in turn, probably in either 470 or 471’.[12]. In what order it is difficult to know, although I think that most of the chronological evidence suggests that the defeat of the British came first and shortly thereafter that the Goths defeated the Romans near Arles before returning north to besiege Clermont-Ferrand.

Where did the British come from?

Before turning to the possible location of King Riothamus’s defeat, if it wasn’t at Déols, we might ask where this British army had come from. There are only two possible answers. Either they came by sea from the more northerly British/Breton settlement in Armorica (i.e. present-day Brittany) or they came direct from the island of Britain. An insular British origin was argued for by the great Breton/French historian Léon Fleuriot.[13] Not only did Fleuriot argue that Riothamus’s British had came from the island of Britain to support the Emperor Anthemius in Gaul, but he also argued that Riothamus was the Romano-British leader Ambrosius Aurelianus. This rather astonishing claim has since been supported in more modern times by several serious historians.[14] Others have even claimed that Riothamus was King Arthur; most popularly Geoffrey Ashe.[15] The arguments put forward for these claims are long, complex and obscure but, for me at least, they ultimately fail to convince.

Before turning to the possible location of King Riothamus’s defeat, if it wasn’t at Déols, we might ask where this British army had come from. There are only two possible answers. Either they came by sea from the more northerly British/Breton settlement in Armorica (i.e. present-day Brittany) or they came direct from the island of Britain. An insular British origin was argued for by the great Breton/French historian Léon Fleuriot.[13] Not only did Fleuriot argue that Riothamus’s British had came from the island of Britain to support the Emperor Anthemius in Gaul, but he also argued that Riothamus was the Romano-British leader Ambrosius Aurelianus. This rather astonishing claim has since been supported in more modern times by several serious historians.[14] Others have even claimed that Riothamus was King Arthur; most popularly Geoffrey Ashe.[15] The arguments put forward for these claims are long, complex and obscure but, for me at least, they ultimately fail to convince.

But even if we put King Arthur to one side, as I do, the origin of the large and coordinated British force, ten thousand strong, which arrived in Gaul under the leadership of a British king called Riothamus, could well have been Britain itself. On the other hand Riothamus’s force might have consisted of the British/Bretons of the diaspora – as we will see the emperor Anthemius asked the British ‘north of the Loire’ for help

It is with this mention of ‘north of the Loire’ that we can now turn to the only other two mentions of Riothamus’s Britons in the sources we have.

Treason and exile

In the second half of the 460s, the post of Roman Praetorian Prefect of Gaul, the official governor, was held on two occasions by a Gallo-Roman aristocrat called Arvandus. During his second term in office (467 – 468) Arvandus committed an act of treachery against the emperor Anthemius. Probably in 468, or the year before, Arvandus dictated a letter to his secretary addressed to the Gothic king Euric in which he tried to dissuade Euric ‘from concluding peace with ‘the Greek Emperor’ (i.e. Anthemius), urging that instead he should attack the Brittones north of the Loire, and asserting that the law of nations called for a division of Gaul between Visigoth and Burgundian’.

We don’t know if Euric ever got this letter or if he did whether he took any notice of Anthemius’s urgings. We don’t even know if Arvandus’s mention of Brittones was referring to ‘Bretons’ already settled north of the Loire or to an insular British force recently arrived there. But what we do know is that not long afterwards Euric did indeed lead his Goths to fight the British.

Arvandus’s letter must be dated prior to 468, or early in that year, because in 468 he was dismissed from his prefectship of Gaul for a second time and ‘invested with guards’ he was taken as ‘a prisoner bound for Rome’.[16] The Roman Senator Cassiodorus says that Arvandus had wanted to seize the throne; he had ‘wanted to become emperor’.[17]

Roman Senate

In Rome Arvandus was put on trial for treason before the Roman senate and the ‘intercepted letter’ he had written to Gothic king Euric was produced in evidence against him. He twice acknowledged that the letter was indeed his and was condemned to death for treachery. The later intervention of his friend, the influential Gallo-Roman Sidonius Appolinaris, saved his life and the sentence was commuted to exile on an island.

We know these details of Arvandus’s acts and subsequent fate from a letter Sidonius wrote to his friend Vincentius, probably in about 469/70 after he had returned from Rome where, as the letter makes clear, he had personally witnessed the start of Arvandus’s trial. I have reproduced Sidonius’s letter in full at the end of this essay as it is compelling reading.

Sidonius writes to Riothamus

Next we have a letter Sidonius wrote to the British king Riothamus himself. Sidonius was asking for Riothamus’s intervention and help for a Gallo-Roman landowner, probably living in the Auvergne, whose slaves were being enticed away by the Britannis (Britons or Bretons).

I will write once more in my usual strain, mingling compliment with grievance. Not that I at all desire to follow up the first words of greeting with disagreeable subjects, but things seem to be always happening which a man of my order and in my position can neither mention without unpleasantness, nor pass over without neglect of duty. Yet I do my best to remember the burdensome and delicate sense of honour which makes you so ready to blush for others’ faults. The bearer of this is an obscure and humble person, so harmless, insignificant, and helpless that he seems to invite his own discomfiture; his grievance is that the Brittones are secretly enticing his slaves away. Whether his indictment is a true one, I cannot say; but, if you can only confront the parties and decide the matter on its merits, I think the unfortunate man may be able to make good his charge, if indeed a stranger from the country unarmed, abject and impecunious to boot, has ever a chance of a fair or kindly hearing against adversaries with all the advantages he lacks, arms, astuteness, turbulences, and the aggressive spirit of men backed by numerous friends. Farewell.[18]

Sidonius Apollinaris

It can be implied from the letter that Riothamus must have had influence, or even a leadership position acknowledged by the Romans, over the Britons in future Brittany. Whether he was their king or not is not said. It’s also clear that Sidonius had written to Riothamus on previous occasions; he says: ‘I will write once more in my usual strain.’ Also from his mention of a ‘man of my order’ it is pretty certain that he was already Bishop of Clermont-Ferrand at the time, a position he was elevated to in either in 470 (or maybe late 469) by the emperor Anthemius after his return from Rome.

It is to this rough time i.e. around 469/470 that I would date Sidonius’s letter to Riothamus. A later dating is possible and has been argued for, but seems unlikely to me. From 471 to 474 Clermont-Ferrand (Sidonius’s Episcopal seat) was besieged by the Visigoths (certainly after their defeat of the British) and Sidonius was much concerned with its defence. In 474, when Clermont-Ferrand finally fell, Euric sent Sidonius into exile for two years to Capendu and Bordeaux, before allowing him to return again to Clermont in 476 as bishop. The implication of the letter is that it was written from Clermont-Ferrand to Riothamus who might have been situated somewhere ‘north of the Loire’, and most likely before his defeat by the Goths. As we will see, following Riothamus’s defeat by the Goths the survivors fled to Burgundy and we never hear of them again. Any late, post-battle, dating of this letter to Riothamus must rely on a completely unsubstantiated conjecture concerning a return of the British king to Brittany after he and his fighters had fled to Burgundy.

Chronological résumé

To sum up some of the dating evidence: soon after his elevation to the imperial purple in 467, the Emperor Anthemius had requested the help of the Britons against Euric’s Visigoths who had just renounced their fealty to Rome. Whether these Britons were the British of the settlement of Armorica (the ‘Bretons’) or were Britons of the island of Britain, or both, is not known. Then slightly later, in about 467/8, Arvandus, the Roman Prefect of Gaul, wrote to the Goths treacherously suggesting they attack the British ‘north of the Loire’ rather than make common cause with the Empire. A large British army led by King Riothamus subsequently arrived in a fleet of ships somewhere along the Atlantic coast and, while seeking to join up with Roman forces, which never came, they were defeated by the Gothic army.

Most historians agree that this battle was fought in 469 or possibly 470. The evidence suggests this is right, although its equation with Déols is doubtful.

What became of the British?

Jordanes tells us that after the battle the British retreated to Burgundy:

Having lost a great part of his army, he fled with all whom he could save, and came to the neighbouring nation of the Burgundians, then confederate with the Romans…

Burgundian and Gallo-Roman

The Burgundians had crossed the Rhine into Roman Gaul along with various other Germanic tribes in 406. They settled on the Roman left bank of the Rhine, between the river Lauter and the Nahe. They seized Worms, Speyer, and Strasbourg. The Roman emperor Honorius later legitimized their land grab and made them official allies or mercenaries, called foederati. Despite this official Roman status, the Burgundians continued to make raids into the Roman province of Gallia Belgica. Exasperated, the Roman general Aëtius called upon his Hunnish mercenaries for help. Although much is still obscure, probably in two engagements in 436/7 Aëtius and the Huns nearly exterminated the Burgundians under their king Gundahar (Gunther).

The contemporary Iberian chronicler Hydatius wrote: “The Burgundians, who had rebelled, were defeated by the Romans under the general Aëtius.” Prosper of Aquitaine, another contemporary, and closer to the events, wrote: “Aëtius crushed [Gundahar], who was king of the Burgundians living in Gaul. In response to his entreaty, Aëtius gave him peace, which the king did not enjoy for long. For the Huns destroyed him and his people root and branch.”

Wagner’s Ring Cycle

It is alleged that King Gundahar/Gunther and 20,000 Burgundians were slaughtered by the Huns. Gundahar was succeeded as king by his son Gunderic. These events became the kernel of the great German Nibelungenlied epic which so inspired Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle operas.

Following their defeat Aëtius allowed the surviving Burgundians to settle in Savoy, with a capital in Geneva. In 451 the Burgundians helped Aëtius and his primarily Gothic army defeat Attila the Hun at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, near Châlons, a decisive event in European history. Following the defeat Attila withdrew and never threatened Gaul again.

In 455 the Burgundians, under Gunderic and his brother Chilperic, accompanied Theodoric’s Visigoths to Spain to fight the Sueves on behalf of the Romans. After their return Lyon became the Burgundian capital in 461.

So by 469 the Germanic Burgundians, with their capital now in Lyon, were still Roman allies. The Visigoths however had by this time repudiated any nominal allegiance to the Roman Empire and were trying to extend their hegemony further north from their kingdom of Toulouse.

As this report makes clear, Riothamus and the British survivors of the defeat at the hands of the Goths retreated to Burgundy because it was ‘confederate with the Romans’:

Ambrosius Aurelianus

What became of these British is not known. Some suggest they returned to Britain (if Riothamus was either King Arthur or another Romano-British chieftain such as Ambrosius Aurelianus). Others think they might have returned to Brittany. To be honest we don’t know. Maybe they were even granted lands in Burgundy and blended into the local mix of Gallo-Romans and Germanic Burgundians?

The question remains: why had the defeated British fled to Burgundy? Of course Burgundy offered a safe haven because the Burgundians like the British were Roman allies opposing the threatening Goths. But geographically Burgundy only makes sense if the British defeat at the hands of the Goths took place at a place from where it made more sense to retreat to Burgundy (possibly to Lyon) than it did to flee northwest to the comparatively safe British settlements in Armorica. Where might the battle have been if it wasn’t Déols?

The location of the battle

As well as the fact that it seems that we can date the clash between the Goths and the Britons at Bourges and Déols some years before 469, there are three additional reasons why I think that the battle is unlikely to have taken place at Déolsand and might well have happened somewhere in the Auvergne.

First, all historians agree that the main objective of the Goths in these years was to secure an occupation of the Auvergne, and particularly the city of Clermont-Ferrand (Arverna). This the Romans wanted to prevent. It is instructive to note that immediately after mentioning the British defeat Jordanes says: ‘But Euric, king of the Visigoths, seized Auvergne, a city of Gaul…..When Euric, as we have already said, beheld these great and various changes, he seized the city of Arverna, where the Roman general Ecdicius was at that time in command.’

First, all historians agree that the main objective of the Goths in these years was to secure an occupation of the Auvergne, and particularly the city of Clermont-Ferrand (Arverna). This the Romans wanted to prevent. It is instructive to note that immediately after mentioning the British defeat Jordanes says: ‘But Euric, king of the Visigoths, seized Auvergne, a city of Gaul…..When Euric, as we have already said, beheld these great and various changes, he seized the city of Arverna, where the Roman general Ecdicius was at that time in command.’

From 471 the Goths besieged Clermont-Ferrand, which resisted valiantly under General Ecdicius and Sidonius himself. But the city was finally captured in 474. When the British were defeated just before this siege began, they had been waiting to join up with a Roman force which never came. In fact by this time the ‘forces’ available to the Gallo-Romans were pretty insignificant and what forces there were could likely have been holed up in cities such as Clermont in fear of a coming Gothic attack. As already suggested, it seems likely that the British were expecting to meet the army from Rome led by Emperor Anthemius’s son Anthemiolus, which never arrived and was defeated itself by the Goths near Arles.

In this context a site for the battle somewhere in the Auvergne, possibly somewhere near Clermont, seems possible.

The Auvergne neighbouring Burgundy

The second reason for my suggestion of the Auvergne as a likely place for the battle has to do with geography. As mentioned, the Burgundian capital had been established in Lyon in 462. We can couple this fact with Jordanes’ explicit statement that Riothamus ‘having lost a great part of his army… fled with all whom he could save, and came to the neighbouring nation of the Burgundians, then confederate with the Romans’. Now Burgundy and Lyon are certainly immediate neighbours of the Auvergne and Clermont, whereas under no circumstances could Bourges/Déols be described as neighbourly. Lyon and Bourges are in fact a long way away from each other. In addition, as I have suggested already, if the battle took place at Déols why would the defeated British have marched an enormous distance from there to Burgundy, across dangerous Gothic-invested land, rather than simply return quickly northwest to the safe British settlements ‘north of the Loire’, whether by land or sea?

Finally, as also mentioned already, perhaps the major supporting evidence for the equation of the events at Bourges/Déols with Riothamus’s battle is Jordanes’ mention of the fact that: ‘King Riothimus, coming with twelve thousand by way of Ocean, and disembarking from his ships, was received into the city/state of the Bituriges.’ Conventionally this city/state of the Bituriges is identified with Bourges, which lies a long way inland in the very north of Aquitaine. But as I have shown this identification is by no means secure. Bituriges could just as well have been further south along the Aquitaine coast, even as far south as Bordeaux, as it might have been somewhere on the more northerly coast from where the British would have had to march a long way to reach Bourges. The evidence is too scanty for us to be certain where this disembarkation took place, but if the city of Clermont-Ferrand was so critical (which it was) then if you want to get there you’d be much better advised, then as now, to land somewhere in Aquitaine, and from there take the direct route to the Auvergne, than you would to land much farther north and face a very long trip indeed via Bourges to get anywhere near Clermont. All this is of course conjecture.

Conclusion

The British defeat at the hands of the Visigoths was not the only time that British (or Bretons as they became) were involved in the centuries-long struggle for the destiny of post-Roman Gaul, but as far as we know it was the first. Ultimately it doesn’t really matter if the battle took place at Déols or elsewhere as I am suggesting, but it’s interesting to draw a parallel between the fate of some Celtic British refugees fleeing the ‘English’ and fighting with one Roman emperor and the fate of some English fleeing the Norman conquerors six hundred years later to fight for an eastern Roman emperor (see here).

Appendix: Sidonius’s letter to Vincentius c. 469/70

THE case of Arvandus distresses me, nor do I conceal my distress, for it is our emperor’s crowning praise that a condemned prisoner may have friends who need not hide their friendship. I was more intimate with this man than it was safe to be with one so light and so unstable, witness the odium lately kindled against me on his account, the flame of which has scorched me for this lapse from prudence. But since I had given my friendship, honour bound me fast, though he on his side has no steadfastness at all; I say this because it is the truth and not to strike him when he is down. For he despised friendly advice and made himself throughout the sport of fortune; the marvel to me is, not that he fell at last, but that he ever stood so long. How often he would boast of weathering adversity, when we, with a less superficial sense of things, deplored the sure disaster of his rashness, unable to call happy any man who only sometimes and not always deserves the name.

But now for your question as to his government; I will tell you in few words, and with all the loyalty due to a friend however far brought low. During his first term as prefect his rule was very popular; the second was disastrous. Crushed by debt, and living in dread of creditors, he was jealous of the nobles from among whom his successor must needs be chosen. He would make fun of all his visitors, profess astonishment at advice, and spurn good offices; if people called on him too rarely, he showed suspicion; if too regularly, contempt. At last the general hate encompassed him like a rampart; before he was well divested of his authority, he was invested with guards, and a prisoner bound for Rome. Hardly had he set foot in the city when he was all exultation over his fair passage along the stormy Tuscan coast, as if convinced that the very elements were somehow at his bidding.

At the Capitol, the Count of the Imperial Largess, his friend Flavius Asellus, acted as his host and jailer, showing him deference for his prefectship, which seemed, as it were, yet warm, so newly was it stripped from him. Meanwhile, the three envoys from Gaul arrived upon his heels with the provincial decrees2 empowering them to impeach in the public name. They were Tonantius Ferreolus, the ex-prefect, and grandson, on the mother’s side, of the Consul Afranius Syagrius, Thaumastus, and Petronius, all men practised in affairs and eloquent, all conspicuous ornaments of our country. They brought, with other matters entrusted to them by the province, an intercepted letter, which Arvandus’ secretary, now also under arrest, declared to have been dictated by his master. It was evidently addressed to the King of the Goths, whom it dissuaded from concluding peace with ‘the Greek Emperor’, urging that instead he should attack the Bretons north of the Loire, and asserting that the law of nations called for a division of Gaul between Visigoth and Burgundian.

There was more in the same mad vein, calculated to inflame a choleric king, or shame a quiet one into action. Of course the lawyers found here a flagrant case of treason. These tactics did not escape the excellent Auxanius and myself; in whatever way we might have incurred the impeached man’s friendship, we both felt that to evade the consequences at this crisis of his fate would be to brand us as traitors, barbarians, and poltroons. We at once exposed to the unsuspecting victim the whole scheme which a prosecution, no less astute than alert and ardent, intended to keep dark until the trial; their scheme was to noose in some unguarded reply an adversary rash enough to repudiate the advice of all his friends and rely wholly on his own unaided wits. We told him what to us and to more secret friends seemed the one safe course; we begged him not to give the slightest point away which they might try to extract from him on pretence of its insignificance; their dissimulation would be ruinous to him if it drew incautious admissions in answer to their questions. When he grasped our point, he was beside himself; he suddenly broke out into abuse, and cried: ‘Begone, you and your nonsensical fears, degenerate sons of prefectorian fathers; leave this part of the affair to me; it is beyond an intelligence like yours. Arvandus trusts in a clear conscience; the employment of advocates to defend him on the charge of bribery shall be his one concession.’

We came away in low spirits, disturbed less by the insult to ourselves than by a real concern; what right has the doctor to take offence when a man past cure gives way to passion? Meanwhile, our defendant goes off to parade the Capitol square, and in white raiment too; he finds sustenance in the sly greetings which he receives; he listens with a gratified air as the bubbles of flattery burst about him. He casts curious eyes on the gems and silks and precious fabrics of the dealers, inspects, picks up, unrolls, beats down the prices as if he were a likely purchaser, moaning and groaning the whole time over the laws, the age, the senate, the emperor, and all because they would not right him then and there without investigation.

A few days passed, and, as I learned afterwards (I had left Rome in the interim), there was a full house in the senate-hall. Arvandus proceeded thither freshly groomed and barbered, while the accusers waited the decemvirs’1 summons unkempt and in half-mourning, snatching from him thus the defendant’s usual right, and securing the advantage of suggestion which the suppliant garb confers. The parties were admitted and, as the custom is, took up positions opposite each other. Before the proceedings began, all of prefectorian rank were allowed to sit; instantly Arvandus, with that unhappy impudence of his, rushed forward and forced himself almost into the very bosoms of the judges, while the ex-prefect* gained subsequent credit and respect by placing himself quietly and modestly amidst his colleagues at the lowest end of the benches, to show that his quality of envoy was his first thought, and not his rank as senator.

While this was going on, absent members of the house came in; the parties stood up and the envoys set forth their charge. They first produced their mandate from the province, then the already-mentioned letter; this was being read sentence by sentence, when Arvandus admitted the authorship without even waiting to be asked. The envoys rejoined, rather cruelly, that the fact of his dictation was obvious. And when the madman, blind to the depth of his fall, dealt himself a deadly blow by repeating the avowal not once, but twice, the accusers raised a shout, and the judges cried as one man that he stood convicted of treason out of his own mouth. Scores of legal precedents were on record to achieve his ruin.

Only at this point, and then not at once, is the wretched man said to have turned white in tardy repentance of his loquacity, recognizing all too late that it is possible to be convicted of high treason for other offences than aspiring to the purple. He was stripped on the spot of all the privileges pertaining to his prefecture, an office which by re-election he had held five years, and consigned to the common jail as one not now first degraded to plebeian rank, but restored to it as his own.

Eye-witnesses report, as the most pathetic feature of all, that as a result of his intrusion upon his judges in all that bravery and smartness while his accusers dressed in black, his pitiable plight won him no pity when he was led off to prison a little later. How, indeed, could anyone be much moved at his fate, seeing him haled to the quarries or hard labour still all trimmed and pomaded like a fop? Judgement was deferred a bare fortnight. He was then condemned to death, and flung into the island of the Serpent of Epidaurus. There, an object of compassion even to his enemies, his elegance gone, spewed, as it were, by Fortune out of the land of the living, he now drags out by benefit of Tiberius’ law his respite of thirty days after sentence, shuddering through the long hours at the thought of hook and Gemonian stairs, and the noose of the brutal executioner.

We, of course, whether in Rome or out of it, are doing all we can; we make daily vows, we redouble prayers and supplications that the imperial clemency may suspend the stroke of the drawn sword, and rather visit a man already half dead with confiscation of property, and exile. But whether Arvandus has only to expect the worst, or must actually undergo it, he is surely the most miserable soul alive if, branded with such marks of shame; he has any other desire than to die.

Notes and references:

[1] Léon Fleuriot, Les origines de la Bretagne: l’émigration. Paris 1980.

[2] For the date 441 see: R. Burgess, The Gallic Chronicle of 511: A New Critical Edition with a Brief Introduction, in Society and Culture in Late Antique Gaul: Revisiting the Sources. ed. R. W. Mathisen and D. Shantzer. Aldershot 2001.

[3] James Ingram, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, London 1823 and 1912: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/medieval/ang05.asp

[4] M. Winterbottom, Gildas, De Excidio britanniae, Chichester 1978.

[5] T. M. Charles-Edwards, Wales and the Britons 300-1064, Oxford 2014, p. 58.

[6] Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, ed. and trans. Lewis Thorpe, 1974.

[7] R. Mathisen, Anthemius (12 April 467 – 11 July 472 A.D.), De Imperatoribus Romanis.

[8] Penny MacGeorge, Late Roman Warlords, Oxford 2002, pp.102-103.

[9] MacGeorge, Warlords.

[10] Jordanes, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, ed. and trans. Charles Christopher Mierow, The Gothic History of Jordanes, 1915.

[11] The Gallic Chronicle of 511: A New Critical Edition with a Brief Introduction, in Society and Culture in Late Antique Gaul: Revisiting the Sources. ed. R. W. Mathisen and D. Shantzer. Aldershot 2001.

[12] Idem

[13] Léon Fleuriot, Les origines de la Bretagne: l’émigration. Paris 1980.

[14]For example: John Morris, The Age of Arthur, a History of the British Isles from 350 to 650, London 1973.

[15]Geoffrey Ashe, The Discovery of King Arthur. New York 1985.

[16] O. M. Dalton, ed. and trans., The Letters of Sidonius, Oxford 1915..

[17] James J. O’Donnell, Cassiodorus, Berkeley 1979.

[18] Dalton, The Letters of Sidonius

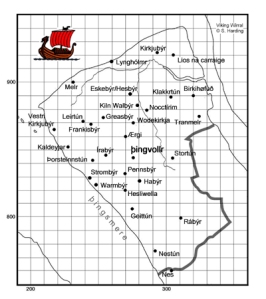

In North Meols and along the nearby River Ribble and its tributary the River Douglas the Vikings would have found many convenient places to ground their ships. As suggested, the area was either not inhabited or only sparsely so. In the records we find not one mention of any confrontation between these Scandinavians and any resident peoples. This implies that the settlement was fairly peaceable. The great historian of English place names, Eilert Ekwall, suggested that this is ‘only a hypothesis’ because it is an argument ‘from silence’, meaning that this view comes only from the fact that there are no written records of clashes between Scandinavian settlers and native inhabitants.[13] Frederick Wainwright, by far the greatest historian of the Scandinavian settlement of north-west England, wrote that the evidence for the peaceable nature of the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire ‘is none the less powerful… since it is almost inconceivable that an organized military conquest or a violent social upheaval, even in the remote north-west, should altogether escape the notice of both contemporary and later annalists’. Wainwright added:

In North Meols and along the nearby River Ribble and its tributary the River Douglas the Vikings would have found many convenient places to ground their ships. As suggested, the area was either not inhabited or only sparsely so. In the records we find not one mention of any confrontation between these Scandinavians and any resident peoples. This implies that the settlement was fairly peaceable. The great historian of English place names, Eilert Ekwall, suggested that this is ‘only a hypothesis’ because it is an argument ‘from silence’, meaning that this view comes only from the fact that there are no written records of clashes between Scandinavian settlers and native inhabitants.[13] Frederick Wainwright, by far the greatest historian of the Scandinavian settlement of north-west England, wrote that the evidence for the peaceable nature of the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire ‘is none the less powerful… since it is almost inconceivable that an organized military conquest or a violent social upheaval, even in the remote north-west, should altogether escape the notice of both contemporary and later annalists’. Wainwright added: As in Cumbria further north, between the Mersey and the Ribble we find Scandinavian place names everywhere. In the immediate vicinity of North Meols itself we find Crossens, Birkdale, Ainsdale, Formby, Altcar, Crosby, Litherland and Kirkdale. Inland we find Scarisbrick, Tarlscough, Tarleton, Ormskirk, Kellamerg and Hesketh. These are all Norse names. The same is true up and down the coast.[15] If we were to add in lesser names of fields and topographical features the list would be almost endless.

As in Cumbria further north, between the Mersey and the Ribble we find Scandinavian place names everywhere. In the immediate vicinity of North Meols itself we find Crossens, Birkdale, Ainsdale, Formby, Altcar, Crosby, Litherland and Kirkdale. Inland we find Scarisbrick, Tarlscough, Tarleton, Ormskirk, Kellamerg and Hesketh. These are all Norse names. The same is true up and down the coast.[15] If we were to add in lesser names of fields and topographical features the list would be almost endless.

The British monk Gildas wrote of the subsequent sufferings of the British:

The British monk Gildas wrote of the subsequent sufferings of the British:

Most of these events mentioned by Gregory can be confirmed and cross-checked from other sources. Importantly they seem to have taken place in the order mentioned by Gregory. The earliest events, such as Childeric at Orleans and a plague, can be dated to 463/4. In the middle we read that ‘Euric, the king of the Visigoths, observing the frequent changes of the Roman princes, attempted to seize the Gauls for his own’. Euric became king in 466. The last sentence concerning an earthquake can be dated to 467/8. Hydatius wrote that ‘in the second year of the emperor Anthemius blood burst forth from the ground in the middle of Toulouse and continued to flow for an entire day’, and Anthemius became Emperor in 467. As historian Penny MacGeorge comments about the period:

Most of these events mentioned by Gregory can be confirmed and cross-checked from other sources. Importantly they seem to have taken place in the order mentioned by Gregory. The earliest events, such as Childeric at Orleans and a plague, can be dated to 463/4. In the middle we read that ‘Euric, the king of the Visigoths, observing the frequent changes of the Roman princes, attempted to seize the Gauls for his own’. Euric became king in 466. The last sentence concerning an earthquake can be dated to 467/8. Hydatius wrote that ‘in the second year of the emperor Anthemius blood burst forth from the ground in the middle of Toulouse and continued to flow for an entire day’, and Anthemius became Emperor in 467. As historian Penny MacGeorge comments about the period:

Before turning to the possible location of King Riothamus’s defeat, if it wasn’t at Déols, we might ask where this British army had come from. There are only two possible answers. Either they came by sea from the more northerly British/Breton settlement in Armorica (i.e. present-day Brittany) or they came direct from the island of Britain. An insular British origin was argued for by the great Breton/French historian Léon Fleuriot.[13] Not only did Fleuriot argue that Riothamus’s British had came from the island of Britain to support the Emperor Anthemius in Gaul, but he also argued that Riothamus was the Romano-British leader Ambrosius Aurelianus. This rather astonishing claim has since been supported in more modern times by several serious historians.[14] Others have even claimed that Riothamus was King Arthur; most popularly Geoffrey Ashe.[15] The arguments put forward for these claims are long, complex and obscure but, for me at least, they ultimately fail to convince.

Before turning to the possible location of King Riothamus’s defeat, if it wasn’t at Déols, we might ask where this British army had come from. There are only two possible answers. Either they came by sea from the more northerly British/Breton settlement in Armorica (i.e. present-day Brittany) or they came direct from the island of Britain. An insular British origin was argued for by the great Breton/French historian Léon Fleuriot.[13] Not only did Fleuriot argue that Riothamus’s British had came from the island of Britain to support the Emperor Anthemius in Gaul, but he also argued that Riothamus was the Romano-British leader Ambrosius Aurelianus. This rather astonishing claim has since been supported in more modern times by several serious historians.[14] Others have even claimed that Riothamus was King Arthur; most popularly Geoffrey Ashe.[15] The arguments put forward for these claims are long, complex and obscure but, for me at least, they ultimately fail to convince.

First, all historians agree that the main objective of the Goths in these years was to secure an occupation of the Auvergne, and particularly the city of Clermont-Ferrand (Arverna). This the Romans wanted to prevent. It is instructive to note that immediately after mentioning the British defeat Jordanes says: ‘But Euric, king of the Visigoths, seized Auvergne, a city of Gaul…..When Euric, as we have already said, beheld these great and various changes, he seized the city of Arverna, where the Roman general Ecdicius was at that time in command.’

First, all historians agree that the main objective of the Goths in these years was to secure an occupation of the Auvergne, and particularly the city of Clermont-Ferrand (Arverna). This the Romans wanted to prevent. It is instructive to note that immediately after mentioning the British defeat Jordanes says: ‘But Euric, king of the Visigoths, seized Auvergne, a city of Gaul…..When Euric, as we have already said, beheld these great and various changes, he seized the city of Arverna, where the Roman general Ecdicius was at that time in command.’