‘And oft tyne oððe twelfe, ælc æfter oþrum, scendað to bysmore þæs þegenes cwenan and hwilum his dohtor oððe nydmagan þær he on locað þe læt hine sylfne rancne and ricne and genoh godne ær þæt gewurde.’

‘God ure helpe, amen.’

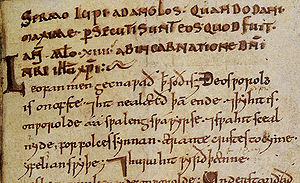

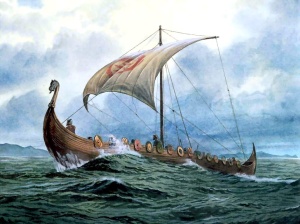

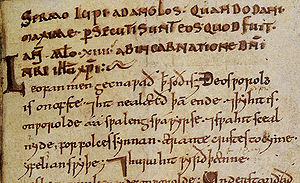

At the end of the tenth century England once more started to suffer from Scandinavian Viking raids. It was to the luckless English king Æthelred that fell the unenviable task of trying to fight them off. Æthelred is known to generations of English schoolchildren as Æthelred the Unready. This name is both unfair and incorrect. In later times chroniclers called Æthelred ‘Unraed’, an Old English word which means ill-counselled or badly advised; it’s certainly nothing to do with unreadiness. For a short time at the start of the millennium the Danish king Swein gained the crown of England, but after his death Æthelred came back from his brief exile in Normandy. He, and later his son, King Edmund ‘Ironside’, continued their struggle against the Danes, only to eventually lose when Edmund died and Swein’s son Knut (‘Canute’) became king of England in 1016. I will return to some of these events at a later time. But here I’d simply like to bring to your attention a remarkable ‘sermon’ or address made in 1014 by the Archbishop of York, Wulfstan, to the people of England. Its Latin title is Sermo Lupi ad anglos: The Sermon (or address) of the Wolf to the English. Despite its Latin title the rest of the address is in Old English.

Later I reproduce the full text of Wulfstan’s sermon, in both modern English and in the original Old English (or Anglo-Saxon). It is a story of the suffering of the people of England, but it is also much more.

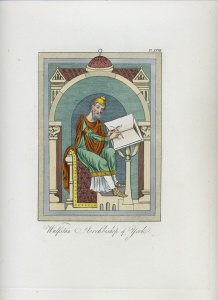

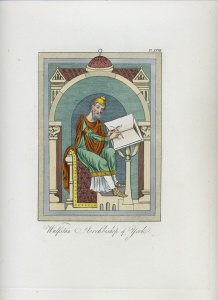

Wulfstan (sometimes Lupus) was an English Bishop of London and Worcester and Archbishop of York.

Wulfstan of York

‘He is thought to have begun his ecclesiastical career as a Benedictine monk. He became the Bishop of London in 996. In 1002 he was elected simultaneously to the diocese of Worcester and the archdiocese of York, holding both in plurality until 1016, when he relinquished Worcester; he remained archbishop of York until his death. It was perhaps while he was at London that he first became well known as a writer of sermons, or homilies, on the topic of Antichrist. In 1014, as archbishop, he wrote his most famous work, a homily which he titled the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, or the Sermon of the Wolf to the English.’

‘Besides sermons Wulfstan was also instrumental in drafting law codes for both kings Æthelred the Unready and Cnut the Great of England. He is considered one of the two major writers of the late Anglo-Saxon period in England. After his death in 1023, miracles were said to have occurred at his tomb, but attempts to have him declared a saint never bore fruit.’

Wulfstan’s ‘Sermo Lupi’

Given the time when Wulfstan wrote the sermon at the beginning of the new Millennium, it was, perhaps unsurprisingly, infused with religious Millenarianism. The end of the world was nigh, the sufferings of the people of England has been brought on them because of their own sins, but there was still a chance of redemption if they returned to a righteous life.

Beloved men, know that which is true: this world is in haste and it nears the end. And therefore things in this world go ever the longer the worse, and so it must needs be that things quickly worsen, on account of people’s sinning from day to day, before the coming of Antichrist.

And indeed it will then be awful and grim widely throughout the world. Understand also well that the Devil has now led this nation astray for very many years, and that little loyalty has remained among men, though they spoke well.

And too many crimes reigned in the land, and there were never many of men who deliberated about the remedy as eagerly as one should, but daily they piled one evil upon another, and committed injustices and many violations of law all too widely throughout this entire land.

The myth of King ‘Canute’

The people of England, says Wulfstan, have ‘endured many injuries and insults’, but they have ‘earned the misery that is upon us’. He then goes on at great length explaining all the sins of the English and how they have not heeded the word of God and have worshipped false gods. He continues:

And sanctuaries are too widely violated, and God’s houses are entirely stripped of all dues and are stripped within of everything fitting.

And widows are widely forced to marry in unjust ways and too many are impoverished and fully humiliated; and poor men are sorely betrayed and cruelly defrauded, and sold widely out of this land into the power of foreigners, though innocent; and infants are enslaved by means of cruel injustices, on account of petty theft everywhere in this nation.

And the rights of freemen are taken away and the rights of slaves are restricted and charitable obligations are curtailed. Free men may not keep their independence, nor go where they wish, nor deal with their property just as they desire; nor may slaves have that property which, on their own time, they have obtained by means of difficult labour, or that which good men, in Gods favour, have granted them, and given to them in charity for the love of God. But every man decreases or withholds every charitable obligation that should by rights be paid eagerly in God’s favour, for injustice is too widely common among men and lawlessness is too widely dear to them.

And in short, the laws of God are hated and his teaching despised; therefore we all are frequently disgraced through God’s anger, let him know it who is able. And that loss will become universal, although one may not think so, to all these people, unless God protects us.

Vikings arrive with mythic wimgs

It is all this that has brought the wrath of God (or the Danes) upon the people of England:

… it is clear and well seen in all of us that we have previously more often transgressed than we have amended, and therefore much is greatly assailing this nation.

It is here that Wulfstan turns his attention to what has been happening in England:

Nothing has prospered now for a long time either at home or abroad, but there has been military devastation and hunger, burning and bloodshed in nearly every district time and again.

And stealing and slaying, plague and pestilence, murrain and disease, malice and hate, and the robbery by robbers have injured us very terribly.

And excessive taxes have afflicted us, and storms have very often caused failure of crops; therefore in this land there have been, as it may appear, many years now of injustices and unstable loyalties everywhere among men.

Now very often a kinsman does not spare his kinsman any more than the foreigner, nor the father his children, nor sometimes the child his own father, nor one brother the other.

Neither has any of us ordered his life just as he should, neither the ecclesiastic according to the rule nor the layman according to the law. But we have transformed desire into laws for us entirely too often, and have kept neither precepts nor laws of God or men just as we should. Neither has anyone had loyal intentions with respect to others as justly as he should, but almost everyone has deceived and injured another by words and deeds; and indeed almost everyone unjustly stabs the other from behind with shameful assaults and with wrongful accusations — let him do more, if he may.

More follows about disloyalty and betrayal, alluding at least in part to a supposed, but certainly much vilified, English traitor, the Mercian ealdorman Eadric Streona (the Grabber). Here we start to hear about some of the things the return of the Danes has brought to England: slavery and the sale of women:

And too many Christian men have been sold out of this land, now for a long time, and all this is entirely hateful to God, let him believe it who will. Also we know well where this crime has occurred, and it is shameful to speak of that which has happened too widely.

And it is terrible to know what too many do often, those who for a while carry out a miserable deed, who contribute together and buy a woman as a joint purchase between them and practice foul sin with that one woman, one after another, and each after the other like dogs that care not about filth, and then for a price they sell a creature of God

All this Wulfstan had seen himself, certainly during his time as Bishop of London and probably later as well. But he and the English had witnessed more:

And pirates are so strong through the consent of God, that often in battle one drives away ten, and two often drive away twenty, sometimes fewer and sometimes more, entirely on account of our sins.

And often ten or twelve, each after the other, insult the thane’s woman disgracefully, and sometimes his daughter or close kinswomen, while he looks on, he that considered himself brave and strong and good enough before that happened.

Stereotypical Viking Rape and Pillage

Let us be clear what Wulfstan is saying here when he says ‘and often ten or twelve, each after the other, insult the thane’s woman disgracefully’

And oft tyne oððe twelfe, ælc æfter oþrum, scendað to bysmore þæs þegenes cwenan and hwilum his dohtor oððe nydmagan þær he on locað þe læt hine sylfne rancne and ricne and genoh godne ær þæt gewurde.

English women are being gang raped as their helpless fathers and brothers are forced to look on.

As if this wasn’t enough, like all priestly elites of the time, Wulfstan is as much concerned with the world being turned upside down as he is about slavery, rape and death. The established order of things has changed; the lower orders have forgotten their place.

And often a slave binds very fast the thane who previously was his lord and makes him into a slave through God’s anger. Alas the misery and alas the public shame that the English now have, entirely through God’s anger.

Often two sailors, or three for a while, drive the droves of Christian men from sea to sea — out through this nation, huddled together, as a public shame for us all, if we could seriously and properly know any shame. But all the insult that we often suffer, we repay by honouring those who insult us. We pay them continually and they humiliate us daily; they ravage and they burn, plunder and rob and carry to the ship; and lo! what else is there in all these happenings except God’s anger clear and evident over this nation?

Thanes are made slaves, herded onto ships to be taken to Scandinavia or to the slave markets of Europe, there possibly to be sold to the Muslims of North Africa. And while suffering all this, the English still have to pay the Danes vast amounts of money, ‘Danegeld’. ‘We pay them continually and they humiliate us daily,’

King Edmund Ironside meets Cnut (‘Canute’)

More follows on the sins of the people of England that have brought all this suffering upon them.

Here in the country, as it may appear, too many are sorely wounded by the stains of sin. Here there are, as we said before, manslayers and murderers of their kinsmen, and murderers of priests and persecutors of monasteries, and traitors and notorious apostates, and here there are perjurers and murderers, and here there are injurers of men in holy orders and adulterers, and people greatly corrupted through incest and through various fornications, and here there are harlots and infanticides and many foul adulterous fornicators, and here there are witches and sorceresses, and here there are robbers and plunderers and pilferers and thieves, and injurers of the people and pledge-breakers and treaty-breakers, and, in short, a countless number of all crimes and misdeeds.

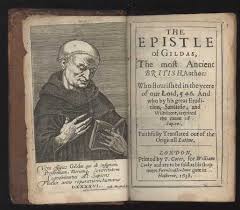

Gildas’s Ruin and Destruction of Britain

Here Wulfstan reminds the English people of the similar sins and sufferings of the native Britons when the Anglo-Saxons had come to Britain in the fifth century. He refers to the writings of the sixth-century British monk Gildas who gave a similar sermon called De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, ‘On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain’. In Chapter 24 Gildas wrote:

For the fire of vengeance, justly kindled by former crimes, spread from sea to sea, fed by the hands of our foes in the east, and did not cease, until, destroying the neighbouring towns and lands, it reached the other side of the island, and dipped its red and savage tongue in the western ocean.

Wulfstan himself writes:

There was a historian in the time of the Britons, called Gildas, who wrote about their misdeeds, how with their sins they infuriated God so excessively that He finally allowed the English army to conquer their land, and to destroy the host of the Britons entirely.

And that came about, just as he said, through breach of rule by the clergy and through breach of laws by laymen, through robbery by the strong and through coveting of ill-gotten gains, violations of law by the people and through unjust judgments, through the sloth of the bishops and folly, and through the wicked cowardice of messengers of God, who swallowed the truths entirely too often and they mumbled through their jaws where they should have cried out; also through foul pride of the people and through gluttony and manifold sins they destroyed their land and they themselves perished.

But is all lost? Is there no hope? Here Wulfstan follows Gildas in believed that hope lies in religious and moral reform:

But let us do as is necessary for us, take warning from such; and it is true what I say, we know of worse deeds among the English than we have heard of anywhere among the Britons; and therefore there is a great need for us to take thought for ourselves, and to intercede eagerly with God himself.

And let us do as is necessary for us, turn towards the right and to some extent abandon wrong-doing, and eagerly atone for what we previously transgressed; and let us love God and follow God’s laws, and carry out well that which we promised when we received baptism, or those who were our sponsors at baptism; and let us order words and deeds justly, and cleanse our thoughts with zeal, and keep oaths and pledges carefully, and have some loyalty between us without evil practice.

And let us often reflect upon the great Judgment to which we all shall go, and let us save ourselves from the welling fire of hell torment, and gain for ourselves the glories and joys that God has prepared for those who work his will in the world. God help us. Amen.

Below I give Wulfstan’s full sermon in modern and Old English. I have added some rather arbitrary paragraph breaks to make it slightly easier to follow.

——————————————————————————————–

The sermon of the Wolf to the English, when the Danes were greatly persecuting them, which was in the year 1014 after the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ:

Beloved men, know that which is true: this world is in haste and it nears the end. And therefore things in this world go ever the longer the worse, and so it must needs be that things quickly worsen, on account of people’s sinning from day to day, before the coming of Antichrist.

And indeed it will then be awful and grim widely throughout the world. Understand also well that the Devil has now led this nation astray for very many years, and that little loyalty has remained among men, though they spoke well.

And too many crimes reigned in the land, and there were never many of men who deliberated about the remedy as eagerly as one should, but daily they piled one evil upon another, and committed injustices and many violations of law all too widely throughout this entire land.

And we have also therefore endured many injuries and insults, and if we shall experience any remedy then we must deserve better of God than we have previously done. For with great deserts we have earned the misery that is upon us, and with truly great deserts we must obtain the remedy from God, if henceforth things are to improve. Lo, we know full well that a great breach of law shall necessitate a great remedy, and a great fire shall necessitate much water, if that fire is to be quenched.

And it is also a great necessity for each of men that he henceforth eagerly heed the law of God better than he has done, and justly pay God’s dues. In heathen lands one does not dare withhold little nor much of that which is appointed to the worship of false gods; and we withhold everywhere God’s dues all too often.

And in heathen lands one dares not curtail, within or without the temple, anything brought to the false gods and entrusted as an offering.

And we have entirely stripped God’s houses of everything fitting, within and without, and God’s servants are everywhere deprived of honour and protection.

And some men say that no man dare abuse the servants of false gods in any way among heathen people, just as is now done widely to the servants of God, where Christians ought to observe the law of God and protect the servants of God.

But what I say is true: there is need for that remedy because God’s dues have diminished too long in this land in every district, and laws of the people have deteriorated entirely too greatly, since Edgar died.

And sanctuaries are too widely violated, and God’s houses are entirely stripped of all dues and are stripped within of everything fitting. And widows are widely forced to marry in unjust ways and too many are impoverished and fully humiliated; and poor men are sorely betrayed and cruelly defrauded, and sold widely out of this land into the power of foreigners, though innocent; and infants are enslaved by means of cruel injustices, on account of petty theft everywhere in this nation.

And the rights of freemen are taken away and the rights of slaves are restricted and charitable obligations are curtailed. Free men may not keep their independence, nor go where they wish, nor deal with their property just as they desire; nor may slaves have that property which, on their own time, they have obtained by means of difficult labour, or that which good men, in Gods favour, have granted them, and given to them in charity for the love of God. But every man decreases or withholds every charitable obligation that should by rights be paid eagerly in Gods favour, for injustice is too widely common among men and lawlessness is too widely dear to them.

And in short, the laws of God are hated and his teaching despised; therefore we all are frequently disgraced through God’s anger, let him know it who is able. And that loss will become universal, although one may not think so, to all these people, unless God protects us.

Therefore it is clear and well seen in all of us that we have previously more often transgressed than we have amended, and therefore much is greatly assailing this nation.

Nothing has prospered now for a long time either at home or abroad, but there has been military devastation and hunger, burning and bloodshed in nearly every district time and again.

And stealing and slaying, plague and pestilence, murrain and disease, malice and hate, and the robbery by robbers have injured us very terribly. And excessive taxes have afflicted us, and storms have very often caused failure of crops; therefore in this land there have been, as it may appear, many years now of injustices and unstable loyalties everywhere among men.

Now very often a kinsman does not spare his kinsman any more than the foreigner, nor the father his children, nor sometimes the child his own father, nor one brother the other. Neither has any of us ordered his life just as he should, neither the ecclesiastic according to the rule nor the layman according to the law. But we have transformed desire into laws for us entirely too often, and have kept neither precepts nor laws of God or men just as we should.

Neither has anyone had loyal intentions with respect to others as justly as he should, but almost everyone has deceived and injured another by words and deeds; and indeed almost everyone unjustly stabs the other from behind with shameful assaults and with wrongful accusations — let him do more, if he may.

For there are in this nation great disloyalties for matters of the Church and the state, and also there are in the land many who betray their lords in various ways. And the greatest of all betrayals of a lord in the world is that a man betrays the soul of his lord. And it is the greatest of all betrayals of a lord in the world, that a man betray his lord’s soul. And a very great betrayal of a lord it is also in the world, that a man betray his lord to death, or drive him living from the land, and both have come to pass in this land: Edward was betrayed, and then killed, and after that burned; and Æthelred was driven out of his land.

And too many sponsors and godchildren have been killed widely throughout this nation, in addition to entirely too many other innocent people who have been destroyed entirely too widely.

And entirely too many holy religious foundations have deteriorated because some men have previously been placed in them who ought not to have been, if one wished to show respect to God’s sanctuary.

And too many Christian men have been sold out of this land, now for a long time, and all this is entirely hateful to God, let him believe it who will. Also we know well where this crime has occurred, and it is shameful to speak of that which has happened too widely.

And it is terrible to know what too many do often, those who for a while carry out a miserable deed, who contribute together and buy a woman as a joint purchase between them and practice foul sin with that one woman, one after another, and each after the other like dogs that care not about filth, and then for a price they sell a creature of God — His own purchase that He bought at a great cost — into the power of enemies.

Also we know well where the crime has occurred such that the father has sold his son for a price, and the son his mother, and one brother has sold the other into the power of foreigners, and out of this nation. All of those are great and terrible deeds, let him understand it who will. And yet what is injuring this nation is still greater and manifold: many are forsworn and greatly perjured and more vows are broken time and again, and it is clear to this people that God’s anger violently oppresses us, let him know it who can.

And lo! How may greater shame befall men through the anger of God than often does us for our own sins? Although it happens that a slave escape from a lord and, leaving Christendom becomes a Viking, and after that it happens again that a hostile encounter takes place between thane and slave, if the slave kills the thane, he lies without wergild paid to any of his kinsmen; but if the thane kills the slave that he had previously owned, he must pay the price of a thane.

Full shameful laws and disgraceful tributes are common among us, through God’s anger, let him understand it who is able. And many misfortunes befall this nation time and again. Things have not prospered now for a long time neither at home nor abroad, but there has been destruction and hate in every district time and again, and the English have been entirely defeated for a long time now, and very truly disheartened through the anger of God.

And pirates are so strong through the consent of God, that often in battle one drives away ten, and two often drive away twenty, sometimes fewer and sometimes more, entirely on account of our sins.

And often ten or twelve, each after the other, insult the thane’s woman disgracefully, and sometimes his daughter or close kinswomen, while he looks on, he that considered himself brave and strong and good enough before that happened. And often a slave binds very fast the thane who previously was his lord and makes him into a slave through God’s anger.

Alas the misery and alas the public shame that the English now have, entirely through God’s anger. Often two sailors, or three for a while, drive the droves of Christian men from sea to sea — out through this nation, huddled together, as a public shame for us all, if we could seriously and properly know any shame. But all the insult that we often suffer, we repay by honouring those who insult us. We pay them continually and they humiliate us daily; they ravage and they burn, plunder and rob and carry to the ship; and lo! what else is there in all these happenings except Gods anger clear and evident over this nation?

It is no wonder that there is mishap among us: because we know full well that now for many years men have too often not cared what they did by word or deed; but this nation, as it may appear, has become very corrupt through manifold sins and through many misdeeds: through murder and through evil deeds, through avarice and through greed, through stealing and through robbery, through man-selling and through heathen vices, through betrayals and through frauds, through breaches of law and through deceit, through attacks on kinsmen and through manslaughter, through injury of men in holy orders and through adultery, through incest and through various fornications.

And also, far and wide, as we said before, more than should be are lost and perjured through the breaking of oaths and through violations of pledges, and through various lies; and non-observances of church feasts and fasts widely occur time and again. And also there are here in the land Gods adversaries, degenerate apostates, and hostile persecutors of the Church and entirely too many grim tyrants, and widespread despisers of divine laws and Christian virtues, and foolish deriders everywhere in the nation, most often of those things that the messengers of God command, and especially those things that always belong to Gods law by right.

And therefore things have now come far and wide to that full evil way that men are more ashamed now of good deeds than of misdeeds; because too often good deeds are abused with derision and the Godfearing are blamed entirely too much, and especially are men reproached and all too often greeted with contempt who love right and have fear of God to any extent. And because men do that, entirely abusing all that they should praise and hating too much all that they ought to love, therefore they bring entirely too many to evil intentions and to misdeeds, so that they are never ashamed though they sin greatly and commit wrongs even against God himself. But on account of idle attacks they are ashamed to repent for their misdeeds, just as the books teach, like those foolish men who on account of their pride will not protect themselves from injury before they might no longer do so, although they all wish for it.

Here in the country, as it may appear, too many are sorely wounded by the stains of sin. Here there are, as we said before, manslayers and murderers of their kinsmen, and murderers of priests and persecutors of monasteries, and traitors and notorious apostates, and here there are perjurers and murderers, and here there are injurers of men in holy orders and adulterers, and people greatly corrupted through incest and through various fornications, and here there are harlots and infanticides and many foul adulterous fornicators, and here there are witches and sorceresses, and here there are robbers and plunderers and pilferers and thieves, and injurers of the people and pledge-breakers and treaty-breakers, and, in short, a countless number of all crimes and misdeeds. And we are not at all ashamed of it, but we are greatly ashamed to begin the remedy just as the books teach, and that is evident in this wretched and corrupt nation.

Alas, many a great kinsman can easily call to mind much in addition which one man could not hastily investigate, how wretchedly things have fared now all the time now widely throughout this nation. And indeed let each one examine himself well, and not delay this all too long. But lo, in the name of God, let us do as is needful for us, protect ourselves as earnestly as we may, lest we all perish together.

There was a historian in the time of the Britons, called Gildas, who wrote about their misdeeds, how with their sins they infuriated God so excessively that He finally allowed the English army to conquer their land, and to destroy the host of the Britons entirely. And that came about, just as he said, through breach of rule by the clergy and through breach of laws by laymen, through robbery by the strong and through coveting of ill-gotten gains, violations of law by the people and through unjust judgments, through the sloth of the bishops and folly, and through the wicked cowardice of messengers of God, who swallowed the truths entirely too often and they mumbled through their jaws where they should have cried out; also through foul pride of the people and through gluttony and manifold sins they destroyed their land and they themselves perished.

But let us do as is necessary for us, take warning from such; and it is true what I say, we know of worse deeds among the English than we have heard of anywhere among the Britons; and therefore there is a great need for us to take thought for ourselves, and to intercede eagerly with God himself. And let us do as is necessary for us, turn towards the right and to some extent abandon wrong-doing, and eagerly atone for what we previously transgressed; and let us love God and follow God’s laws, and carry out well that which we promised when we received baptism, or those who were our sponsors at baptism; and let us order words and deeds justly, and cleanse our thoughts with zeal, and keep oaths and pledges carefully, and have some loyalty between us without evil practice.

And let us often reflect upon the great Judgment to which we all shall go, and let us save ourselves from the welling fire of hell torment, and gain for ourselves the glories and joys that God has prepared for those who work his will in the world. God help us. Amen.

——————————————————————————————

Sermo Lupi ad anglos quando Dani maxime persecuti sunt eos,

quod fuit anno millesimo .xiiii. ab incarnatione

Domine Nostri Iesu Cristi

Leofan men, gecnawað þæt soð is: ðeos worold is on ofste, and hit nealæcð þam ende, and þy hit is on worolde aa swa leng swa wyrse; and swa hit sceal nyde for folces synnan ær Antecristes tocyme yfelian swyþe, and huru hit wyrð þænne egeslic and grimlic wide on worolde.

Understandað eac georne þæt deofol þas þeode nu fela geara dwelode to swyþe, and þæt lytle getreowþa wæran mid mannum, þeah hy wel spæcan, and unrihta to fela ricsode on lande.

And næs a fela manna þe smeade ymbe þa bote swa georne swa man scolde, ac dæghwamlice man ihte yfel æfter oðrum and unriht rærde and unlaga manege ealles to wide gynd ealle þas þeode.

And we eac forþam habbað fela byrsta and bysmara gebiden, and gif we ænige bote gebidan scylan, þonne mote we þæs to Gode earnian bet þonne we ær þysan dydan.

Forþam mid miclan earnungan we geearnedan þa yrmða þe us onsittað, and mid swyþe micelan earnungan we þa bote motan æt Gode geræcan gif hit sceal heonanforð godiende weorðan.

La hwæt, we witan ful georne þæt to miclan bryce sceal micel bot nyde, and to miclan bryne wæter unlytel, gif man þæt fyr sceal to ahte acwencan.

And micel is nydþearf manna gehwilcum þæt he Godes lage gyme heonanforð georne and Godes gerihta mid rihte gelæste.

On hæþenum þeodum ne dear man forhealdan lytel ne micel þæs þe gelagod is to gedwolgoda weorðunge, and we forhealdað æghwær Godes gerihta ealles to gelome.

And ne dear man gewanian on hæþenum þeodum inne ne ute ænig þæra þinga þe gedwolgodan broht bið and to lacum betæht bið, and we habbað Godes hus inne and ute clæne berypte.

And Godes þeowas syndan mæþe and munde gewelhwær bedælde; and gedwolgoda þenan ne dear man misbeodan on ænige wisan mid hæþenum leodum, swa swa man Godes þeowum nu deð to wide þær Cristene scoldan Godes lage healdan and Godes þeowas griðian.

Ac soð is þæt ic secge, þearf is þære bote, forþam Godes gerihta wanedan to lange innan þysse þeode on æghwylcan ende, and folclaga wyrsedan ealles to swyþe, and halignessa syndan to griðlease wide, and Godes hus syndan to clæne berypte ealdra gerihta and innan bestrypte ælcra gerisena, and wydewan syndan fornydde on unriht to ceorle, and to mænege foryrmde and gehynede swyþe, and earme men syndan sare beswicene and hreowlice besyrwde and ut of þysan earde wide gesealde, swyþe unforworhte, fremdum to gewealde, and cradolcild geþeowede þurh wælhreowe unlaga for lytelre þyfþe wide gynd þas þeode, and freoriht fornumene and þrælriht genyrwde and ælmesriht gewanode.

And, hrædest is to cweþenne, Godes laga laðe and lara forsawene.

And þæs we habbað ealle þurh Godes yrre bysmor gelome, gecnawe se ðe cunne; and se byrst wyrð gemæne, þeh man swa ne wene, eallre þysse þeode, butan God beorge.

Forþam hit is on us eallum swutol and gesene þæt we ær þysan oftor bræcan þonne we bettan, and þy is þysse þeode fela onsæge.

Ne dohte hit nu lange inne ne ute, ac wæs here and hunger, bryne and blodgyte, on gewelhwylcan ende oft and gelome.

And us stalu and cwalu, stric and steorfa, orfcwealm and uncoþu, hol and hete and rypera reaflac derede swyþe þearle, and us ungylda swyþe gedrehtan, and us unwedera foroft weoldan unwæstma.

Forþam on þysan earde wæs, swa hit þincan mæg, nu fela geara unriht fela and tealte getrywða æghwær mid mannum.

Ne bearh nu foroft gesib gesibban þe ma þe fremdan, ne fæder his bearne, ne hwilum bearn his agenum fæder, ne broþor oþrum; ne ure ænig his lif ne fadode swa swa he scolde, ne gehadode regollice, ne læwede lahlice, ac worhtan lust us to lage ealles to gelome, and naþor ne heoldan ne lare ne lage Godes ne manna swa swa we scoldan.

Ne ænig wið oþerne getrywlice þohte swa rihte swa he scolde, ac mæst ælc swicode and oþrum derede wordes and dæde, and huru unrihtlice mæst ælc oþerne æftan heaweþ sceandlican onscytan, do mare gif he mæge.

Forþam her syn on lande ungetrywþa micle for Gode and for worolde, and eac her syn on earde on mistlice wisan hlafordswican manege.

And ealra mæst hlafordswice se bið on worolde þæt man his hlafordes saule beswice; and ful micel hlafordswice eac bið on worolde þæt man his hlaford of life forræde oððon of lande lifiendne drife; and ægþer is geworden on þysan earde.

Eadweard man forrædde and syððan acwealde and æfter þam forbærnde.

And godsibbas and godbearn to fela man forspilde wide gynd þas þeode toeacan oðran ealles to manegan þe man unscyldgige forfor ealles to wide.

And ealles to manege halige stowa wide forwurdan þurh þæt þe man sume men ær þam gelogode swa man na ne scolde, gif man on Godes griðe mæþe witan wolde; and Cristenes folces to fela man gesealde ut of þysan earde nu ealle hwile.

And eal þæt is Gode lað, gelyfe se þe wille.

And scandlic is to specenne þæt geworden is to wide and egeslic is to witanne þæt oft doð to manege þe dreogað þa yrmþe, þæt sceotað togædere and ane cwenan gemænum ceape bicgað gemæne, and wið þa ane fylþe adreogað, an after anum and ælc æfter oðrum, hundum gelicost þe for fylþe ne scrifað, and syððan wið weorðe syllað of lande feondum to gewealde Godes gesceafte and his agenne ceap þe he deore gebohte.

Eac we witan georne hwær seo yrmð gewearð þæt fæder gesealde bearn wið weorþe and bearn his modor, and broþor sealde oþerne fremdum to gewealde; and eal þæt syndan micle and egeslice dæda, understande se þe wille.

And git hit is mare and eac mænigfealdre þæt dereð þysse þeode.

Mænige synd forsworene and swyþe forlogene, and wed synd tobrocene oft and gelome, and þæt is gesyne on þysse þeode þæt us Godes yrre hetelice onsit, gecnawe se þe cunne.

And la, hu mæg mare scamu þurh Godes yrre mannum gelimpan þonne us deð gelome for agenum gewyrhtum?

Ðeah þræla hwylc hlaforde ætleape and of Cristendome to wicinge weorþe, and hit æfter þam eft geweorþe þæt wæpengewrixl weorðe gemæne þegene and þræle, gif þræl þæne þegen fullice afylle, licge ægylde ealre his mægðe, and gif se þegen þæne þræl þe he ær ahte fullice afylle, gylde þegengylde.

Ful earhlice laga and scandlice nydgyld þurh Godes yrre us syn gemæne, understande se þe cunne. And fela ungelimpa gelimpð þysse þeode oft and gelome.

Ne dohte hit nu lange inne ne ute, ac wæs here and hete on gewelhwilcan ende oft and gelome, and Engle nu lange eal sigelease and to swyþe geyrgde þurh Godes yrre, and flotmen swa strange þurh Godes þafunge þæt oft on gefeohte an feseð tyne and hwilum læs, hwilum ma, eal for urum synnum.

And oft tyne oððe twelfe, ælc æfter oþrum, scendað to bysmore þæs þegenes cwenan and hwilum his dohtor oððe nydmagan þær he on locað þe læt hine sylfne rancne and ricne and genoh godne ær þæt gewurde.

And oft þræl þæne þegen þe ær wæs his hlaford cnyt swyþe fæste and wyrcð him to þræle þurh Godes yrre.

Wala þære yrmðe and wala þære woroldscame þe nu habbað Engle eal þurh Godes yrre.

Oft twegen sæmen oððe þry hwilum drifað þa drafe Cristenra manna fram sæ to sæ ut þurh þas þeode gewelede togædere, us eallum to woroldscame, gif we on eornost ænige cuþon ariht understandan.

Ac ealne þæne bysmor þe we oft þoliað we gyldað mid weorðscipe þam þe us scendað.

We him gyldað singallice, and hy us hynað dæghwamlice.

Hy hergiað and hy bærnað, rypaþ and reafiað and to scipe lædað; and la, hwæt is ænig oðer on eallum þam gelimpum butan Godes yrre ofer þas þeode, swutol and gesæne?

Nis eac nan wundor þeah us mislimpe, forþam we witan ful georne þæt nu fela geara men na ne rohtan foroft hwæt hy worhtan wordes oððe dæde, ac wearð þes þeodscipe, swa hit þincan mæg, swyþe forsyngod þurh mænigfealde synna and þurh fela misdæda: þurh morðdæda and þurh mandæda, þurh gitsunga and þurh gifernessa, þurh stala and þurh strudunga, þurh mannsylena and þurh hæþene unsida, þurh swicdomas and þurh searacræftas, þurh lahbrycas and þurh æswicas, þurh mægræsas and þurh manslyhtas, þurh hadbrycas and þurh æwbrycas, þurh siblegeru and þurh mistlice forligru.

And eac syndan wide, swa we ær cwædan, þurh aðbricas and þurh wedbrycas and þurh mistlice leasunga forloren and forlogen ma þonne scolde, and freolsbricas and fæstenbrycas wide geworhte oft and gelome.

And eac her syn on earde apostatan abroþene and cyrichatan hetole and leodhatan grimme ealles to manege, and oferhogan wide godcundra rihtlaga and Cristenra þeawa, and hocorwyrde dysige æghwær on þeode oftost on þa þing þe Godes bodan beodaþ and swyþost on þa þing þe æfre to Godes lage gebyriað mid rihte.

And þy is nu geworden wide and side to ful yfelan gewunan, þæt menn swyþor scamað nu for goddædan þonne for misdædan; forþam to oft man mid hocere goddæda hyrweð and godfyrhte lehtreð ealles to swyþe, and swyþost man tæleð and mid olle gegreteð ealles to gelome þa þe riht lufiað and Godes ege habbað be ænigum dæle.

And þurh þæt þe man swa deð þæt man eal hyrweð þæt man scolde heregian and to forð laðet þæt man scolde lufian, þurh þæt man gebringeð ealles to manege on yfelan geþance and on undæde, swa þæt hy ne scamað na þeah hy syngian swyðe and wið God sylfne forwyrcan hy mid ealle, ac for idelan onscytan hy scamað þæt hy betan heora misdæda, swa swa bec tæcan, gelice þam dwæsan þe for heora prytan lewe nellað beorgan ær hy na ne magan, þeah hy eal willan.

Her syndan þurh synleawa, swa hit þincan mæg, sare gelewede to manege on earde.

Her syndan mannslagan and mægslagan and mæsserbanan and mynsterhatan; and her syndan mansworan and morþorwyrhtan; and her syndan myltestran and bearnmyrðran and fule forlegene horingas manege; and her syndan wiccan and wælcyrian.

And her syndan ryperas and reaferas and woroldstruderas and, hrædest is to cweþenne, mana and misdæda ungerim ealra.

And þæs us ne scamað na, ac þæs us scamað swyþe þæt we bote aginnan swa swa bec tæcan, and þæt is gesyne on þysse earman forsyngodon þeode.

Eala, micel magan manege gyt hertoeacan eaþe beþencan þæs þe an man ne mehte on hrædinge asmeagan, hu earmlice hit gefaren is nu ealle hwile wide gynd þas þeode.

And smeage huru georne gehwa hine sylfne and þæs na ne latige ealles to lange.

Ac la, on Godes naman utan don swa us neod is, beorgan us sylfum swa we geornost magan þe læs we ætgædere ealle forweorðan.

An þeodwita wæs on Brytta tidum Gildas hatte.

Se awrat be heora misdædum hu hy mid heora synnum swa oferlice swyþe God gegræmedan þæt he let æt nyhstan Engla here heora eard gewinnan and Brytta dugeþe fordon mid ealle.

And þæt wæs geworden þæs þe he sæde, þurh ricra reaflac and þurh gitsunge wohgestreona, ðurh leode unlaga and þurh wohdomas, ðurh biscopa asolcennesse and þurh lyðre yrhðe Godes bydela þe soþes geswugedan ealles to gelome and clumedan mid ceaflum þær hy scoldan clypian.

Þurh fulne eac folces gælsan and þurh oferfylla and mænigfealde synna heora eard hy forworhtan and selfe hy forwurdan.

Ac utan don swa us þearf is, warnian us be swilcan. And soþ is þæt ic secge, wyrsan dæda we witan mid Englum þonne we mid Bryttan ahwar gehyrdan.

And þy us is þearf micel þæt we us beþencan and wið God sylfne þingian georne.

And utan don swa us þearf is, gebugan to rihte and be suman dæle unriht forlætan and betan swyþe georne þæt we ær bræcan.

And utan God lufian and Godes lagum fylgean, and gelæstan swyþe georne þæt þæt we behetan þa we fulluht underfengan, oððon þa þe æt fulluhte ure forespecan wæran.

And utan word and weorc rihtlice fadian and ure ingeþanc clænsian georne and að and wed wærlice healdan and sume getrywða habban us betweonan butan uncræftan.

And utan gelome understandan þone miclan dom þe we ealle to sculon, and beorgan us georne wið þone weallendan bryne hellewites, and geearnian us þa mærða and þa myrhða þe God hæfð gegearwod þam þe his willan on worolde gewyrcað.

God ure helpe, amen.

The full title of Berresford Ellis’s book is ‘Celt and Saxon. The Struggle for Britain AD 410 – 937’. This gives you some indication of the story he tells: How the ‘Saxons’ first arrived in post-Roman ‘Celtic’ Britain; how over the next centuries these Saxons slowly but surely extended their dominance over much of the southern part of the island of Britain – the region now called England; how the Celtic-speaking native Britons fought back; how even in the tenth century the Celts still dreamt of throwing out the accursed Saxon and Viking invaders and sang ‘The Monarchy of Britain’ (Vnbeinyaeth Prydein) before going into battle. But ultimately how, after the Saxon king Athelstan’s victory over a coalition of Norse-Irish, Scots, Welsh (possibly) and Cumbrian warlords at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, the Celts had to accept that the Saxons and Danes could not be dislodged and how thereafter instead of calling themselves Britons they (or at least the Welsh) started to refer to themselves as Cymry, i.e. Compatriots, hence the present Welsh name for Wales, Cymru, and indeed Cumbria.

The full title of Berresford Ellis’s book is ‘Celt and Saxon. The Struggle for Britain AD 410 – 937’. This gives you some indication of the story he tells: How the ‘Saxons’ first arrived in post-Roman ‘Celtic’ Britain; how over the next centuries these Saxons slowly but surely extended their dominance over much of the southern part of the island of Britain – the region now called England; how the Celtic-speaking native Britons fought back; how even in the tenth century the Celts still dreamt of throwing out the accursed Saxon and Viking invaders and sang ‘The Monarchy of Britain’ (Vnbeinyaeth Prydein) before going into battle. But ultimately how, after the Saxon king Athelstan’s victory over a coalition of Norse-Irish, Scots, Welsh (possibly) and Cumbrian warlords at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, the Celts had to accept that the Saxons and Danes could not be dislodged and how thereafter instead of calling themselves Britons they (or at least the Welsh) started to refer to themselves as Cymry, i.e. Compatriots, hence the present Welsh name for Wales, Cymru, and indeed Cumbria.