Visitors to Ullswater in Cumberland today might take a walk to the waterfall called Aira Force and nearby Lyulph’s Tower, both situated in lovely Gowbarrow Park on the lake’s shore. It’s a place that William Wordsworth visited often. It is believed that he was so taken with the beauty of Gowbarrow that it inspired him to write his most famous poem, The Daffodils:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Lyulph’s Tower today

The present Lyulph’s Tower was built in the 1780s by Charles Howard, the 11th Duke of Norfolk, as a hunting lodge on top of the original Pele Tower. It was a good site for hunting. One visitor a century before commented that it ‘contained more deer than trees’.

From that dim period when ‘ the whole of Britain was a land of uncleared forest, and only the downs and hill-tops rose above the perpetual tracts of wood,’ down to nearly the end of the eighteenth century, red deer roamed wild over Cumberland.

Gowbarrow Hall

Here however I want to go back a little further in time, to the late eleventh and early twelfth-century, to the years following the Norman Conquest. It’s the story of the barony and manor of Greystoke, in which both Matterdale and Watermillock lie, as well as being a story of one family’s accommodation with the Norman invaders. This family became the future lords of Greystoke. I will return to the question of the roots of this family in a subsequent article – were they already ‘magnates’ before the Conquest or were their origins more humble? But first, who was the ‘Cumbrian’ woman who became a king’s mistress? And which king?

Her name was Edith Forne Sigulfson, the daughter of Forne, the son of Sigulf. The king with whom she consorted was Henry I, the son of William the Bastard, better known as William the Conqueror. Henry succeeded to the English throne in 1100 on the death of his brother William II (Rufus).

All kings have taken mistresses, some even have had harems of them. It was, and is, one of the privileges and prerogatives of power. In England the king who took most advantage of this opportunity was the French-speaking Henry I. As well as having two wives, Henry had at least 10 mistresses, by whom he had countless children. How and when Edith and Henry met we will never know. What we do know is that they had at least two children: Adeliza Fitz-Edith, about whom nothing is known, and Robert Fitz-Edith (son of Edith), sometimes called Robert Fitz-Roy (son of the king), who the king married off with Matilda d’Avranches, the heiress of the barony of Oakhampton in Devon.

King Henry seems to have treated his mistresses or concubines better than some of the later English kings (think for instance of his name-sake Henry VIII ). When Henry tired of Edith he married her to Robert D’Oyly (or D’Oiley), the nephew of Robert d’Oyly, a henchman of William the Conqueror who had been with William at Hastings and who built Oxford Castle in 1071.

When Oxford closed its gates against the Conqueror, and he had stormed and taken the city, it followed that he should take measures to keep the people of the place in subjection. Accordingly, having bestowed the town on his faithful follower, Robert d’Oilgi, or D’Oiley or D’Oyly, he directed him to build and fortify a strong castle here, which the Chronicles of Osney Abbey tell us he did between the years 1071 and 1073, “digging deep trenches to make the river flow round about it, and made high mounds with lofty towers and walls thereon, to overtop the town and country about it.” But, as was usual with the Norman castles, the site chosen by D’Oyly was no new one, but the same that had been long before adopted by the kings of Mercia for their residence; the mound, or burh, which was now seized for the Norman keep had sustained the royal house of timber in which had dwelt Offa, and Alfred and his sons, and Harold Harefoot. (Castles Of England, Sir James D. Mackenzie, 1896)

Henry also gave Edith the manor of Steeple Claydon in Buckinghamshire as a dower in her own name. After the original Robert D’Oyly had died in 1090, his younger brother Nigel succeeded him as Constable of Oxford and baron of Hook Norton (i.e. Oxford). Despite the fact that the sixteenth-century chronicler John Leland commented: ‘Of Nigel be no verye famose things written’, in fact he ‘flourished during the reign of William Rufus and officiated as constable of all England under that King’. On Nigel’s death in 1112, his son Robert became the third baron of Hook Norton, the constable of Oxford Castle and, at some point, King’s Henry’s constable.

Several children were soon born to Edith and Robert, including two sons, Gilbert and Henry. It seems Edith was both a ‘very beautiful’ and a very pious woman. Some historians believe that she was remorseful and penitent because of her previous life as King Henry’s concubine. Whatever the truth of this, in 1129 she persuaded her husband Robert to found and endow the Church of St. Mary, in the Isle of Osney, near Oxford Castle. The church would become an abbey in 1149. The story is interesting. Sir John Peshall in The History of Oxford University in 1773 wrote:

Edith, wife of Robert D’Oiley, the second of this name, son of Nigel, used to please herself living with her husband at the castle, with walking here by the river side, and under these shady trees; and frequently observing the magpies gathered together on a tree by the river, making a great chattering, as it were, at her, was induced to ask Radilphus, a Canon of St. Frid, her confessor, whom she had sent to confer upon this matter, the meaning of it.

“Madame”, says he, “these are not pyes; they are so many poor souls in purgatory, uttering in this way their complaints aloud to you, as knowing your extensive goodness of disposition and charity”; and humbly hoped, for the love of God, and the sake of her’s and her posterity’s souls, she would do them some public good, as her husband’s uncle had done, by building the Church and College of St. George.

“Is it so indeed”, said she, “de pardieux. I will do my best endeavours to bring these poor souls to rest”; and relating the matter to her husband, did, by her importunities, with the approbation of Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Alexander, Bishop of Lincoln, and consent of her sons Henry and Gilbert, prevail on him to begin this building there, where the pyes had sat delivering their complaint.

John Leland, the ‘father of English local history and bibliography’, had told much the same tale in the first half of the sixteenth-century:

Sum write that this was the occasion of making of it. Edith usid to walk out of Oxford Castelle with her Gentilwomen to solace, and that often tymes, wher yn a certan place in a tre as often as she cam a certan pyes usid to gether to it, and ther to chattre, and as it wer to speke unto her. Edithe much marveling at this matier, and was sumtyme sore ferid as by a wonder. Whereupon she sent for one Radulph, a Chanon of S. Frediswide’s, a Man of a vertuus Life and her Confessor, asking hym Counsel: to whom he answerid, after that he had seen the fascion of the Pies Chattering only at her Cumming, that she should builde sum Chirch or Monasterie in that Place. Then she entreatid her Husband to build a Priorie, and so he did, making Radulph the first Prior of it.

Osney Abbey

One historian commented: ‘This is a curiously characteristic story. Edith, whose antecedents may have made her suspicious of reproach, was evidently possessed with the idea that the clamour of the magpies was a malicious mockery designed to humiliate and reprove her, and to convey a supernatural warning that she must make speedy atonement for her sins.’ This is, of course, pure conjecture.

Edith even got her son by the king, Robert Fitz-Roy, “Robertus Henrici regis filius”, to contribute to Osney Abbey, with the consent of his half brother “Henrici de Oleio fratris mei”.

Maybe Edith had found peace in the Abbey she helped create. But England was to soon experience another bout of armed thugs fighting armed thugs, fighting that would come very close to Edith. When Henry 1 died in 1135 without a legitimate son he bequeathed his kingdom to his daughter the Empress Matilda (or Maude), the widow of Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, who had since married Geoffrey of Anjou. Aware of the problems with a woman becoming Queen, in 1127 and 1128 Henry had made his court swear allegiance to Matilda; this included Stephen of Blois, a grandson of William the Conqueror. But when Henry died Matilda was in Rouen. ‘Stephen of Blois rushed to England upon learning of Henry’s death and moved quickly to seize the crown from the appointed heir.’ Remember, this was a French not an English family! A war followed between King Stephen and the Empress Matilda.

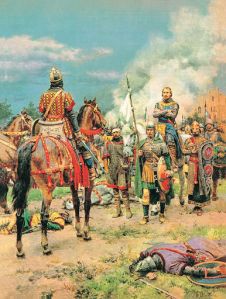

King Stephen captured at Lincoln

But what about Edith and her husband Robert in Oxford? King Stephen tried various inducements to get Robert D’Oyly on his side, but Robert remained loyal to Matilda. Sir James D. Mackenzie wrote:

The second Robert D’Oyly, son to Nigel, the brother of the founder, who succeeded his uncle, and founded the monastery of Osney, nearby, took part against Stephen, and delivered up his castle of Oxford to the Empress Maud for her residence. She accordingly came here with great state in 1141, with a company of barons who had promised to protect her during the absence of her brother, the Earl of Gloucester, in France, whither he had gone to bring back Prince Henry. Gloucester and Stephen had only recently been exchanged against each other, the Earl from Rochester and Stephen from Bristol, and the latter lost no time in opening afresh the civil war, by at once marching rapidly and unexpectedly to Oxford. Here he set fire to the-town and captured it. He then proceeded to shut up closely and to besiege Maud in the castle, from Michaelmas to Christmas, trying to starve out her garrison, whilst from two high mounds which lie raised against the keep, the one called Mount Pelham, and the other Jew’s Mount, he constantly battered the walls and defences with his engines of war, which threw stones and bolts.

Maud, who was a mistress of stratagems and resources—she had escaped from Winchester Castle on a swift horse, by taking advantage of a pretended truce on account of the ceremonies of Holy Cross, and had at Devizes been carried through the enemies lines dressed out as a corpse in a funeral procession—was equal to the occasion when provisions failed. Taking advantage of a keen frost which had frozen over the Isis, she issued one night from a postern, and crossed the river on the ice, accompanied only by three faithful followers. The country being covered with deep snow, they wore white garments over their clothes, and succeeded in eluding their enemies, walking through the snow six long miles to Abingdon. Here a horse was obtained for the Empress, and the party got safely next morning to Wallingford Castle. After her escape, Oxford Castle was yielded to Stephen the next day.

It seems that Robert D’Oyly didn’t long survive these events, but it is still unclear whether he died at King Stephen’s instigation or not. Edith survived him and lived on until 1152. ‘Cumbrian’ Edith Forne Sigulfson, concubine of a king, married to a Norman nobleman, was buried in Osney Abbey. When John Leland visited in the early sixteenth-century, on the eve of its dissolution, he saw her tomb:

‘Ther lyeth an image of Edith, of stone, in th’ abbite of a vowess, holding a hart in her right hand, on the north side of the high altaire’.

The dream of magpies was painted near the tomb. ‘Above the arch over her tomb there was painted on the wall a picture representing the foundation legend of the Abbey, viz. The magpies chattering on her advent to Oseney; the tree; and Radulphe her confessor; which painting, according to Holinshed, was in perfect preservation at the suppression of religious houses (in the time of ) Henry VIII.’

We’ve come a long way from the shores of distant Ullswater. So let’s return there briefly. It is certain that Edith was the daughter of Forne Sigulfson. Forne was the holder of lands in Yorkshire (for example in Nunburnholme) in 1086 when the Domesday survey was taken. Whether he was also already a landowner in Cumberland at that time is unknown because Cumbria was not included in Domesday Book, for the very simple reason that (probably) at the time it was under the Scottish crown.

But Forne certainly became the first ‘Norman’ baron of Greystoke in Henry I’s time. The Testa de Nevill in 1212 reads:

Robert de Veteri Ponte holds in custody from the King the land which was of William son of Ranulf, together with the heir of the aforesaid William, and renders annually of cornage £4. King Henry, grandfather of the King’s father, gave that land to Forne son of Siolf, predecessor of the aforesaid William, by the aforesaid service.

Greystoke Castle

Some historians have suggested that this was actually a reconfirmation of Forne’s existing holdings and rights – whether or not originally granted by Ranulf Meschin, who had been given titular control of Cumbria sometime around 1100. But possibly his rights went back to his father Sigulf in pre-conquest days. This is a subject to which I will return. What is clear is that Forne’s son Ivo was the founder of Greystoke Castle. He built the first defensive tower there in 1129. The family received permission to castellate the tower in 1338. Forne’s ‘Greystoke’ family, as it became known, continued to be Lords of Greystoke in a direct male line until 1306, when more distant relatives succeeded to the title: first the Grimesthorps, then the Dacres and then, in 1571, the Howards.

Was Edith even Cumbrian? We don’t know. Quite possibly she could have been born in Yorkshire on her father’s lands there. In any case, Edith was a northern Anglo-Saxon. We don’t even know when she was born, although I think that the evidence points to her being born in the 1090s or at the latest in the first couple of years of the 1100s. I think she became Henry’s mistress in 1122 following Henry’s one and only visit to York and Carlisle in that year.

What of Lyulph’s Tower and Lake Ullswater? It is generally thought, at least in later times, that Lyulph refers to Sigulf, (often spelt Sygoolf, Llyuph,Ligulf, Lygulf etc), Forne’s father and Edith’s grandfather. It is even suggested that Ullswater is also named after him: ‘Ulf’s Water’.

I’ll leave all that for another time.