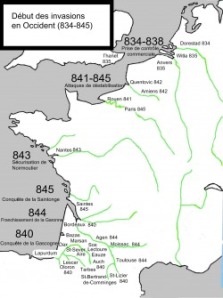

Chaque année, au printemps, les voiles blanches des barques de ces hommes du Nord apparaissaient sur les bords de ces fleuves, le Rhin, la Seine ou la Garonne. Les populations riveraines s’enfuyaient, pleines d’effroi, se dispersaient au loin dans les forêts, ou s’enfermaient dans les villes fortifiées. La Loire, avec son large lit et ses eaux abondantes dans la saison des pluies, leur donnait un accès facile jusqu’au cœur du pays. (Histoire de l’abbaye de Micy-Saint-Mesmin. By L’Abbé Eugène Jarossay, 1902)

Three brothers fight

The Frankish emperor Ludwig ‘the Pious’ (called Louis by the French) died on an island in the Rhine at the end of the year 840. He had reigned through twenty-six troubled and violent years. The Carolingian empire was now falling apart. Since 829 Louis and his sons, Lothar, Ludwig ‘the German’ and Charles ‘the Bald’, had been fighting each other for control of the far-flung but fragile empire that Louis’s father Karl the Great (Charlemagne) had carved out. Each of the three sons was fighting for a large share of their father’s inheritance when he died. Their nephew Pepin II of Aquitaine was also involved.

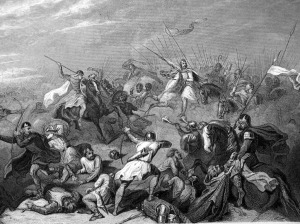

Following Louis the Pious’ death, the years 840-843 were to be marked by the confrontation between the three brothers. In these fights the chief of the Celtic realm of Brittany, Nominoë, initially remained faithful to the western Frankish king, Charles the Bald, who had inherited what one would soon be able to call France. At the start of 841 Charles the Bald went to Le Mans, where he met Lambert, a former count of Nantes. From Le Mans Charles sent an embassy to Nominoë asking him to recognise his authority. According to the Frankish chronicler Nithard, himself a grandson of Charlemagne, Nominoë sent Charles presents and promised to serve him faithfully. He kept his promise because he sent a contingent of Breton warriors to fight in Charles’ army, which on 25 June 841, allied with Louis/Ludwig the German, defeated the forces of their brother Lothar at the horrific but decisive battle of Fontenoy-en-Puisaye, near to Auxerre. It is even possible that Nominoë was also present at the battle.

Lothar had been defeated and the next year his victorious brothers, Ludwig the German and Charles the Bald (who was only eighteen at the time of the battle), met at Strasbourg to make oaths of mutual support and help against Lothar, who wasn’t by any means finished.

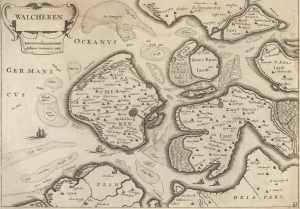

Walcheren

Our concern here is with the story of the city of Nantes, which lies on the River Loire in the march (borderland) of Brittany, and with the Vikings who had been attacking the coasts of Gaul for some time. Lothar had often used the Vikings, usually based on their Frisian island of Walcheren, as allies or mercenaries, to help him fight his brothers. Just one month before the major battle of Fontenoy, a fleet of Viking ships had raided up the River Seine as far as Rouen, arriving just after Charles the Bald’s army had managed to cross the river by tying together boats they had found to make a bridge. Charles was on his way to fight Lothar and the strong suspicion is that the Vikings, under their leader Asgeir, were acting at the behest of Lothar, trying to distract or detain Charles’ army. It is interesting to note that in the same year, 841 (whether before or after the Seine raid is unknown), Lothar officially granted the Frisian island of Walcheren to one of the Vikings who was probably with Asgeir at Rouen. The Frankish chronicler of St. Bertin, Prudentius of Troyes, was disgusted:

To secure the services of Haraldr, who along with other Danish pirates had for some years been imposing many sufferings on Frisia and other coastal regions of the Christians, to the damage of his father’s interests and the furtherance of his own, he (Lothar) now granted him Walcheren and the neighbouring regions as a benefice. This was surely an utterly detestable crime, that those who brought evil on Christians should be given power over the lands and people of Christians, and over the very churches of Christ; that the persecutors of the Christian faith should be sent up as lords over Christians, and Christian folk have to serve men who worshipped demons.

Fight for the county and city of Nantes

Charles the Bald

But the battle of Fontenoy had other consequences. Ricwin, the count of Nantes, had been killed there. Lambert, who had himself fought with Charles at Fontenoy, asked the young king Charles to grant him the county. But Charles for some reason suspected Lambert’s loyalty and granted Nantes instead to the powerful magnate Rainald of Herbauges. This turned Lambert against Charles and he immediately went to meet the Breton Nominoë and asked that the Bretons join him to take Nantes by force. For reasons that remain unclear Nominoë agreed. Perhaps he was fearful of Rainald who now controlled the whole lower Loire or perhaps Lothar had persuaded him to defect and join him.

In the summer of 843, Lothair or perhaps his supporter Lambert II of Nantes succeeded in persuading Nominoe to abandon Charles and go over to the Emperor (i.e. Lothar). Nominoe was thereafter a constant enemy of Charles and his authority in Neustria, often acting in concert with Lothair, Lambert, and Pepin II of Aquitaine. Breton troops fought under Lambert in Neustria and when, in June 844, Charles was besieging Toulouse, Nominoe raided into Maine and plundered the territory. In November 843, Charles had marched as far as Rennes to compel Breton submission, but to no effect.

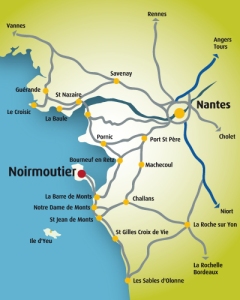

It was in this region that the Vikings were making many of their raids, based each summer on the island of Noirmoutier at the mouth of the River Loire. Rainald had already fought against the Vikings, and it is quite likely that this was the reason Charles the Bald had chosen to appoint such a powerful chief at this crucial spot which controlled access to the rich Loire valley.

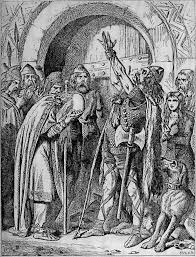

Nominoe

Whatever the case, in 843 Nominoë and Lambert both deserted Charles – implicitly at least in favour of Lothar. They started to march south towards Nantes. Count Rainald, possibly on Charles the Bald’s orders, moved north to meet them. Near the town of Messac on the River Vilaine, which divides Nantes from Vannes, Rainald came across half the Breton force, under Nominoë’s son Erispoë, who had just crossed the river. He attacked, but the Bretons got the upper hand and he had to retreat to the River Yzar, near the village of Blain, where his warriors rested. Lambert hadn’t been at the Messac fight because he was waiting to meet some other Bretons. But he soon joined forces with Erispoë and they soon found and massacred Rainald himself and most of his nobles at Blain. Rainald’s army had been resting unarmed by the river!

Lambert managed to enter Nantes but the citizens threw him out after only two or three weeks.

The Viking attack on Nantes

It is here that the Northmen, the Vikings, enter the story. It is usually said that the Viking army and its raiding fleet, who were based for the summer on the nearby island of Noirmoutier, saw Nantes bereft of defenders and the death of Rainald and most of his vassals and decided to attack and pillage the city. As I will show it might not have been as simple as this.

The basic facts about what happened are not in doubt. The Frankish Annals of St. Bertin report the following:

The basic facts about what happened are not in doubt. The Frankish Annals of St. Bertin report the following:

Northmen pirates attacked Nantes, slew the bishop and many clergy and lay people of both sexes, and sacked the civitas. Then they attacked the western parts of Aquitaine to devastate them too. Finally they landed on a certain island, brought their households from the mainland and decided to winter there in something like a permanent settlement.

In A History of the Vikings Gwyn Jones adds some colour:

The day was 24 June, St. John’s day, and the town was filled with devout or merry celebrants of the Baptist’s feast, The Norwegian assault was of surpassing brutality. The slew in the streets, they slew in the houses, they slew the bishop and congregation in the church. They did their will till nightfall, and the ships they rowed downriver were deep-laden with plunder and prisoners. This may be more than the Count (Lambert) had bargained for but he did acquire Nantes.

I will return to the point of what Lambert might have bargained and whether the raiders were ‘Norwegians’ later. But actually we know quite a lot more about the sack of Nantes from the chroniclers.

There is a story which may or may not be true telling how the Vikings had managed to take the city of Nantes so easily. Lietaud, a tenth-century monk of St. Mesmin wrote about Nantes in his Miracles of St. Martin of Vertou. Using Ferdinand Lot’s summary:

There is a story which may or may not be true telling how the Vikings had managed to take the city of Nantes so easily. Lietaud, a tenth-century monk of St. Mesmin wrote about Nantes in his Miracles of St. Martin of Vertou. Using Ferdinand Lot’s summary:

The Northmen of which nobody had as yet heard spoken, had approached the ramparts (of Nantes) under the pretence of being merchants. The inhabitants who had heard nothing had left the gates open. The pirates entered the town hiding their arms under their clothes and slew the bishop and the population.

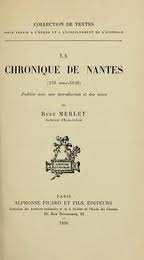

Not only that, but there is also an eyewitness account of what happened at Nantes in 843 written in about 866. In was found by Bertrand d’Argentré in a monument of the Abbey of St. Serge in Angers and published by him in his Histoire de Bretagne in 1588. It was republished in Rene Merlet’s Chronique de Nantes. I will refer to it again later on; here I will just précis a few lines:

After they had disembarked some of them climbed the walls of the city using ladders, others penetrated the cloisters. No one could prevent their entry. The entered the city on the holy festival of St. John the Baptist. The Bishop of the City was Gohardus, a simple, handsome and God-fearing man, with whom all the clergy and monks of the monastery were gathered…

There were also sheltering in the city itself a great multitude of people not only from the immediate region but also from far away towns – who had come not only from fear but also to celebrate the holy day.

Seeing their enemies entering the city walls they ran to the church of the apostles St. Peter and St. Paul and barred the doors against the persecutors, praying for divine deliverance, as they couldn’t save themselves….. The Vikings came in…

The Vikings slew the entire multitude they found there without regard to age or sex. They cruelly killed the priest and bishop Gohardus who died saying ‘Sursum corda’. All the other monks, whether they were in the church, outside it, or at the altar were put to the sword and disembowelled…

This eyewitness then goes on to say that no one could express in words the ‘calamity and pestilence of this painful day’. He couldn’t describe it because of his tears:

Children hanging on their dead mothers’ breasts drank blood rather than milk, the stone flags of the church ran red with the blood of holy men and the holy altar dripped the blood of innocents, The pagans then pillaged all the city, seized all its treasures and set fire to the church. They then took a great numbers of prisoners as hostages for ransom and returned to their ships…

As we know, after sacking Nantes the Vikings continued their raids in the surrounding ‘western parts of Aquitaine’. The Miracles of St. Martin of Vertou tells us something about this too. Again using Lot’s words:

Not being in any hurry, the Northmen redescend the river to the monastery of Indre, situated on an island eight kilometres downstream of Nantes, spared no doubt by reason of prudence before the main attack, was this time burned on 29 June. The monks of St. Vertou, only two leagues from Nantes, had fear and took flight: they found a refuge at St. Varent, in the Thouarsais.

Who were the Vikings who attacked Nantes?

The leader of the Vikings who attacked and plundered Nantes is given nowhere in the sources. Most historians think that he was in fact the same Asgeir who had raided up the River Seine to Rouen two years previously, in 841, and who reappeared on the Seine in 852. I tend to agree he might have been.

However, I think it is also quite possible that among the Viking leaders at Nantes was the famous, or infamous, Hastein/Hasting, who we know took a large fleet up the whole length of the River Garonne all the way to Toulouse in 844 (the year after the sack of Nantes). From there it was probably he who went on to raid in Christian Spain and Muslim Portugal and Andalucía later the same year. Hastein remained an important, and pretty well-attested, Viking leader for some decades. I will return to him on another occasion. But regarding Nantes, there is more evidence of his earlier activities; evidence that has rarely been noticed.

The cathedral of Coutances in present-day Normandy kept a chronicle of its history from the year 836, when it was first attacked by the Vikings. Although this has been lost it was copied in the thirteenth century and we can read what it has to say about Hastein.

Prima Normanorum gravis sima persecutione, nequissimi scilicet et sacrilegi Hasting suorumque praedatorum saeviente amplius quam trigenta annis, ab anno Dominicae incarnationis DCCCXXXVI…

Which roughly translates as follows: ‘The first severe persecution of the Northmen was by the wicked and sacrilegious Hasting, whose predatory violence raged for more than thirty years from year of our Lord 836… ‘ The cathedral of Coutances had been destroyed by Hastein/Hasting in 836, eight years before we find him at the walls of Toulouse.

Which roughly translates as follows: ‘The first severe persecution of the Northmen was by the wicked and sacrilegious Hasting, whose predatory violence raged for more than thirty years from year of our Lord 836… ‘ The cathedral of Coutances had been destroyed by Hastein/Hasting in 836, eight years before we find him at the walls of Toulouse.

It then goes on to describe in great detail the raids and atrocities committed by Hastein all over Flanders, ‘Normandy’, Burgundy and Brittany, as well as elsewhere.

The Chronicle of Tours is also informative:

Lotharii imperatoris anno primo, Hastingus cum innumera Danorum multitudine Franciam ingressus, oppida, rura, vicos, ferro, flamma, fame de populatur.

Which tells us that in the first year of the emperor Lothar (i.e. 841), Hastein came into Francia with innumerable Danes and everywhere destroyed towns and villages, and their people, with sword, flame and hunger.

So it could indeed be that Hastein was one of the Viking leaders at Nantes too.

Having left Rouen in 841, Asgeir and his fleet (whether or not including Hastein) would have returned to one of their island bases, either Walcheren in Frisia or the island of Noirmoutier at the mouth of the River Loire near Nantes. Walcheren was used as a Viking base all year round, even after the summer raiding season was over and their ships put in ‘hangars’. Noirmoutier had been used for some years as a summer base, but the Vikings first over-wintered there in 843/4, after their attack on Nantes.

Noirmoutier

The Translatio sancti Filiberti, composed only twenty years after the event, tells us that the Viking fleet which entered the Loire consisted of sixty-seven ships, ‘Nortmannorum naves sexaginta septem repentio Ligeris…’ The Annals of Angouleme says that these Vikings were ‘Westfaldingi’. Because Vestfold is an area of southern Norway (actually on the west side of the entrance to Oslo Fjord, immediately opposite the Jutland peninsular), this led the German historian Walther Vogel to suggest in 1906 that all these Vikings were ‘Norwegian’, and even that they may have come from the new Viking bases in Ireland. Robert Ferguson wrote in his The Hammer and the Cross that the ‘Norwegian Viking ships… had probably set out from a longphort base in Ireland’. It is a line that other historians have also rather blindly followed; it is unlikely to be true.

The most reliable sources we have for the attack on Nantes are the Chronicle of Nantes and the eyewitness account contained in the ‘Annals of Angers’. These refer both to Northmen and Danes, and thus, as the Danish Viking historian Else Roesdahl has argued, the Viking fleet that attacked Nantes was most likely made up of a mixed group of Danes, Norwegians and even Swedes.

At this time the word Northmen (Latin Nortmanni) was used as a catch-all term meaning any and all people from Scandinavia. Adam of Bremen writing in the north in the eleventh century said, ‘Danes and Swedes and the other peoples beyond Denmark are called Northmen by the historians of the Franks.’

The eyewitness account of 843 contained in the Annals of Angers calls them ‘ferocious Northmen’, while the Chronicle of Nantes itself calls them ‘Northmen and Danes’. The Annals of Fontanelle, written in the Abbey of Fontanelle which Asgeir had plundered on his raid up the Seine in 841, simply says that, ‘in A.D. 841 the Northmen arrived on the twelfth of May with their chief, Asgeir’. It should also be noted that Norway was not yet a definite ‘country’. The province of Vestfold was for a long time claimed as, and de facto was, a part of the realm of the kings of Denmark. In 813 the Frankish Royal Chronicles report that, ‘The kings (of Denmark) were not at home but had marched with an army towards Westarfalda, an area in the extreme northwest of their kingdom’.

The eyewitness account of 843 contained in the Annals of Angers calls them ‘ferocious Northmen’, while the Chronicle of Nantes itself calls them ‘Northmen and Danes’. The Annals of Fontanelle, written in the Abbey of Fontanelle which Asgeir had plundered on his raid up the Seine in 841, simply says that, ‘in A.D. 841 the Northmen arrived on the twelfth of May with their chief, Asgeir’. It should also be noted that Norway was not yet a definite ‘country’. The province of Vestfold was for a long time claimed as, and de facto was, a part of the realm of the kings of Denmark. In 813 the Frankish Royal Chronicles report that, ‘The kings (of Denmark) were not at home but had marched with an army towards Westarfalda, an area in the extreme northwest of their kingdom’.

Of course it could well be that Asgeir himself was originally from Vestfold, along with many others in the Nantes fleet, but the explicit mention of ‘Danes’ as well as the generic ‘Northmen’ in the Chronicle of Nantes points, as Professor Roesdahl suggests, to a ‘multinational’ force.

Whatever the precise combination of geographic origins of the Viking at Nantes, the idea that they had come from Ireland (having sailed round the north of Britain it is said) seems a pure invention of Professor Vogel in 1906. It is far more likely that they had come either from the Viking island base of Walcheren in Frisia or, possibly, from a base in Denmark itself. The ‘Westfaldingi’ at Nantes were, I believe, under Danish control, royal or not.

Was Count Lambert in league with the Vikings?

Over the years it has been repeatedly suggested that the Viking attack on Nantes wasn’t simply an opportunistic raid by the Northmen based on the island of Noirmoutier once they saw that Nantes was defenceless, but that actually it was the result of an agreement between the former count of Nantes and the Viking leaders. Even the very authoritative Professor Gwyn Jones in A History of the Vikings wrote that ‘the rebel Count Lambert was ambitious to secure Nantes for himself’; and that ‘it is said that the Vikings came at his invitation, and that it was French pilots who conned them through the sandbanks, shallows, and uncertain watercourses, which in high summer were judged an absolute protection from naval assault’. Many other historians disagree for reasons I shall give. Professor Jones’ use of the sitting-on-the-fence passive construction ‘it is said’ perhaps indicates the uncertainty of the matter.

The eyewitness account in the Annals of Angers says the following:

The eyewitness account in the Annals of Angers says the following:

Triginta autem post haec elapsis diebus, mense junio , Normannorum ferox natio, numerosa classe advecti, Ligerim fluvium, qui inter novam Britanniam et ultimos Aquitaniae fines in occiduum mergitur Oceanum, ingrediuntur. Deinde, dato classibus zephiro, ad urbem Namneticam, impiissimo Lamberto, crebro exploratore, praecognitam, celeri carbasorum volatu pariter et remorum impulsu contendunt ; quam mox navibus egressi undique vallant, et sine mora, nullo propugnatore, capiunt, vastant, diripiunt…

Regarding Lambert this doesn’t tell us too much except that thirty days after the battle (of Messac/Blain on 24th May 843) he was ‘impious’ or traitorous and led the Viking ships up the Loire to Nantes to sack the city.

The tenth-century chronicler of Nantes tells us more. The editor of the chronicles, Rene Merlet, argued persuasively that the Nantes chronicler had a longer version of the ninth-century report now included in the Annals of Angers available; how else would he have got so much extra information? The chronicler says that after the battle of Fontenoy in 841, Lambert had asked Charles the Bald to return the county of Nantes to him, but Charles had refused, suspecting his loyalty, and had given it instead to Rainald. And so Lambert had gone to meet the Breton chief Nominoë and asked him to join forces and that they should go together to take Nantes by force. Nominoë agreed.

River Vilaine at Messac

When Count Rainhald heard of this he gathered a great number of his ‘knights’ together and went to meet the Bretons at Messac on the River Vilaine, which marked the frontier of the counties of Nantes and Vannes. When Rainald arrived at the river he found that half of the Bretons had already crossed so he attacked them and the Bretons had to flee. Rainald then retreated to the banks of the River Ysar near Blain. Lambert hadn’t been at Messac because he had been waiting for other Bretons to join him. The two Breton armies then joined and quickly attacked Rainald’s forces at Blain; and because they had been resting unarmed on the ‘verdant’ riverbank the Bretons had been able to massacre them, and Count Rainhald was killed.

But, writes the Nantes chronicler, Lambert still wasn’t content, he wanted to seize the city of Nantes, so he went to get the help of the ‘Northmen and Danes who had often plundered throughout Gaul and Neustria’ (i.e. the kingdom of the west Franks):

Namque Normannos et Danos, quos superius diximus, fines Gallorum et Neustriensium maritimos navigando saepe depraedantes, ut erat affabilis et pro tune fuit inventor malorum, alloquens induxit,ut,per mare Oceanum navigantes, Britanniam novam circumirent, et per alveum Ligeris tutissime ad urbem Namneticam capiendam per venirent.

Being an eloquent plotter of evil deeds, Lambert had persuaded the Vikings to put to sea and he led then safely round the coasts of ‘new’ Brittany and up the River Loire to the city of Nantes. The city soon fell because it was defenceless; those who should have been defending it were all dead. We then hear that while the Vikings were ‘greedily’ ravaging and plundering the city Lambert told them of a church full of gold and silver on the island of ‘Bas’ (Batz, behind St. Nazaire). So the Vikings gathered together all their ships and, led by Lambert who showed them the way, they rowed through the bays and coves of Brittany to Bas.

Being an eloquent plotter of evil deeds, Lambert had persuaded the Vikings to put to sea and he led then safely round the coasts of ‘new’ Brittany and up the River Loire to the city of Nantes. The city soon fell because it was defenceless; those who should have been defending it were all dead. We then hear that while the Vikings were ‘greedily’ ravaging and plundering the city Lambert told them of a church full of gold and silver on the island of ‘Bas’ (Batz, behind St. Nazaire). So the Vikings gathered together all their ships and, led by Lambert who showed them the way, they rowed through the bays and coves of Brittany to Bas.

To sum up the case for the prosecution regarding Lambert’s culpability: The eyewitness report in the Annals of Angers implicates him. The chronicler of Nantes, probably basing his story on a longer but now lost version of the Angers document, clearly states that not only had Lambert gone to the ‘Northmen and Danes’ to induce them to come with him to retake Nantes, but he also says that Lambert then attracted them to take their pillaging into other regions of the Nantaise as well. Although there is a lot of obscurity and questions of chronology, the case against Lambert looks strong.

Chronique de Nantes

Evidence to the contrary comes, once again, from the Nantes Chronicle. Here we are told that after the Vikings had taken and sacked the city and had ravaged other places in the region they took their booty and hostages/slaves back to their island liar of Noirmoutier. But once there and having hauled the enormous piles of plunder ashore in order to share it out, the Northmen had quarrelled about the division. The Northmen ‘forgot the fear of their princes’ and it came to fights; several were killed. Seeing this, their ‘Christian captives’ managed to escape via ‘secret places’ on the island. One managed to take with him a chest containing a bible and other books which, the chronicler tells us, ‘are still kept in the church of Nantes’. Finally these ‘diabolical’ men were pacified and went back to their ships, but ‘because of fear of Lambert’ they dared not chase the escaped Christians who ‘God had delivered from their hands’.

It is because of this story that both the editor of the Nantes Chronicle, Rene Merlet, and the eminent French historians Ferdinand Lot and Louis Halphen, in their La Regne de Charles le Chauve (1909), reject the suggestion, so clear in the texts, that Lambert was in league with the Northmen. If the Viking didn’t pursue the escaped captives out of fear of Lambert then surely they were not allies? One could think of others reasons for this fear but it’s probably fair to say that we’ll never really know if Count Lambert was in league with the Vikings are not. I tend to the belief that he was.

Coincidences or Policy?

When we start to look at the precise timing of the various Viking raids around the coasts of France, Brittany and Aquitaine during this period, we might start to ask if they were all spontaneous or opportunistic as they are often presented. The coincidences do seem to get too much.

Vikings take Paris in 845

Why was Asgeir’s Viking fleet raiding up the Seine to Rouen in 841 immediately after Charles the Bald’s army had just managed to cross the river by using a bridge of boats; just one month before the decisive battle of Fontenoy between Charles, Louis and their brother Lothar? In 844, why did the Viking fleet make its long rapacious trip down the River Garonne in Aquitaine to arrive at the walls of Toulouse at the same time that Charles the Bald arrived to repress his nephew Pepin of Aquitaine? I could go on.

While there is little doubt that the Northmen did often strike when the ‘targets’ were in disarray, and this was certainly the case all over ‘France’ in the 840s, they were also very much involved in the shifting power politics being played out in Europe at the time – though often as rather irritating minor players. Robert Ferguson sums it up:

The chaos (of these times) was compounded by the fact that the Danish royal families too were, for much of the time, engaged in dynastic struggles of their own, in the course of which it becomes very difficult to keep track of a meaningful distinction between, on the one hand, violent activity that might have been part of a coherent ‘foreign policy’ decided upon by a legitimate monarch and his advisers and carried out by a ‘national’ army, and, on the other, those actions – often the work of the same kings – which were more nothing more than privateering on a grand scale.

Sources and references:

René Toustain de Billy, Histoire Ecclésiastique du Diocèse de Coutances, 1874; René Merlet, La Chronique de Nantes, 1896; Ferdinand Lot and Louis Halphen, La Règne de Charles le Chauve, 1909 ; L’Abbé Eugène Jarossay, Histoire de l’abbaye de Micy-Saint-Mesmin, 1902; Gwyn Jones, A History of the Vikings, 1968;Robert Ferguson, The Hammer and the Cross, 2009; Carolingian Chronicles, trans Berhard Walter Scholz, 2006; Janet L Nelson, The Annals of St-Bertin, 1991; Else Roesdahl, The Vikings, 1998; Peter Sawyer, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, 1997; Walther Vogel, Die Normannen und das frankische Reich bis zur Griindung der Normandie (799-911), 1906; Bertrand d’Argentré, L’histoire de Bretaigne, des roys, ducs, comtes et princes d’icelle: l’établissement du Royaume, mutation de ce tiltre en Duché, continué jusques au temps de Madame Anne dernière Duchesse, & depuis Royne de France, par le mariage de laquelle passa le Duché en la maison de France, 1588.

Fascinating stuff. Much more conflict to follow, of course, such as the Battle of Jengland and the subsequent use of Vikings by both the Bretons and the Franks to attack each other’s territory, until the calamitous Viking takeover of Brittany and the ruin of Nantes in the early 900s, forcing the Breton nobility to flee to Edward the Elder’s England, this being followed by the return of Duke Alan II in 936, the Loire Vikings’ come-uppance and the temporary collapse of Normandy.