“The arrival of Captain Boycott, who has involuntarily added a new word to the language, is an event of something like international interest” – New York Tribune

Professional Yorkshireman Geoffrey Boycott

When you hear the word Boycott what do you think about? Is it the likeable but rather annoying ‘professional’ Yorkshireman and cricketer Geoffrey Boycott? A man who never realised the best thing about Yorkshire is the motorway to Lancashire. Or do you think of the noun and the verb: ‘The Rugby Football Union has imposed a boycott on South Africa’; ‘The Unites States has boycotted the Moscow Olympics’?

Boycott is indeed a family name, but the noun and the verb came into our language from an interesting source.

According to James Redpath, the verb “to boycott” was coined by Father O’Malley in a discussion between them on 23 September 1880. The following is Redpath’s account:

I said, “I’m bothered about a word.”

“What is it?” asked Father John.

“Well,” I said, “When the people ostracise a land-grabber we call it social excommunication, but we ought to have an entirely different word to signify ostracism applied to a landlord or land-agent like Boycott. Ostracism won’t do – the peasantry would not know the meaning of the word – and I can’t think of any other.”

“No,” said Father John, “ostracism wouldn’t do”

He looked down, tapped his big forehead, and said: “How would it do to call it to Boycott him?”

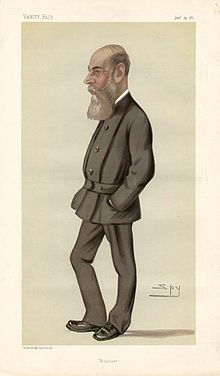

Charles Cunningham Boycott from Vanity Fair in 1881

What was this all about? Well it was all to do with the long fight of the Irish to gain ‘home rule’ from Britain. Wikipedia has an excellent article which begins as follows:

Charles Cunningham Boycott (12 March 1832 – 19 June 1897) was a British land agent whose ostracism by his local community in Ireland gave the English language the verb to boycott. He had served in the British Army 39th Foot, which brought him to Ireland. After retiring from the army, Boycott worked as a land agent for Lord Erne (John Crichton, 3rd Earl Erne), a landowner in the Lough Mask area of County Mayo.

In 1880, as part of its campaign for the Three Fs (fair rent, fixity of tenure and free sale), the Irish Land League under Charles Stewart Parnell and Michael Davitt withdrew the local labour required to harvest the crops on Lord Erne’s estate and began a campaign of isolation against Boycott in the local community. This campaign included the refusal of shops in nearby Ballinrobe to serve him, and the withdrawal of laundry services. According to Boycott, the boy who carried his mail was threatened with violence if he continued.

The campaign against Boycott became a cause célèbre in the British press after he wrote a letter to The Times; newspapers sent correspondents to the West of Ireland to highlight what they viewed as the victimisation of a servant of a peer of the realm by Irish nationalists. Fifty Orangemen from County Cavan and County Monaghan travelled to Lord Erne’s estate to harvest the crops, while a regiment of troops and more than 1,000 men of the Royal Irish Constabulary were deployed to protect the harvesters. The episode was estimated to have cost the British government and others at least £10,000 to harvest about £500 worth of crops.

Boycott left Ireland on 1 December 1880 and in 1886 he became land agent for Hugh Adair’s Flixton estate in Suffolk. He died at the age of 65 on 19 June 1897 in his home in Flixton after an illness earlier that year.

Actually there’s much more to tell about this episode, particularly the rather typical reaction of the British government, but I’ll leave it here.

I was alerted to this little vignette by John O’Farrell in his fabulous book An Utterly Impartial History of Britain, truthfully subtitled Or 2000 years of Upper Class Idiots in Charge. O’Farrell says that he got a B in his O level History at Desborough Comprehensive (more than I did as I didn’t do O level History), but although all the reviews of the book stress how funny it is (which it certainly is) I have to say that it’s also damned good and spot-on history. You really should read it, especially if you don’t really read history books; academic historians could learn a lot.