In three previous articles I kept hovering around Gospatric, an earl of Northumbria in the eleventh century. Sometime before or after the Norman Conquest he issued a writ granting the use of some of his lands in northern Cumbria to one of his men: Thorfinn Mac Thore. It’s a fascinating document not least because it is written in old English (Anglo-Saxon). It’s also about the only such written source we have concerning the governance of Cumbria in the pre-Norman era, i.e. before King William Rufus first captured Carlisle in 1092. But who was Gospatric?

Saint Patrick

It’s been a question which has generated several conflicting answers over the years. Let me start my own investigation with his name. Gospatric (or Gospatrick) is a British name and means ‘Servant of Patrick’.

The Cumbric personal names Gospatrick, Gososwald and Gosmungo meaning ‘servant of St…’ (Welsh/Cornish/Breton gwas ‘servant, boy’) and the Galloway dialect word gossock ‘short, dark haired inhabitant of Wigtownshire’ (Welsh gwasog ‘a servant’) apparently show that the Cumbric equivalent of Welsh/Cornish gwas & Breton gwaz ‘servant’ was *gos.

Patrick refers to Saint Patrick, who was, and still is, the patron saint of Ireland, but who was originally a mainland British-born ‘Celt’ before being captured by Irish pirates and brought up in Ireland.

The languages the native British and Irish spoke at the time of the Anglo-Saxon advent in the fifth and later centuries are usually grouped by linguists into two groups: Goidelic, which includes Irish and Scots Gaelic, and Brythonic, which includes what is now Welsh and, importantly for us, Cumbric; plus Cornish and Breton.

Gospatric is undoubtedly a Brythonic Cumbric name.

Cymru

The Brythonic (‘British’) languages were all basically just variants of the same language. The Welsh today call their language Cymraeg and themselves Cymry. The country is called Cymru. The French version is Cambria, as in the Cambrian Mountains. The same people who lived in the north-western region of present-day England and over a large swathe of southern ‘Scotland’ were called Cumbrians; their land Cumbria and their language Cumbric. It’s the same word for essentially the same people. From this we obviously get modern Cumbria and the anglicized Cumberland. All these names are descended from the Brythonic word combrogi, meaning ‘fellow-countrymen’.

The use of the word Cymry as a self-designation derives from the post-Roman era relationship of the Welsh with the Brythonic-speaking peoples of northern England and southern Scotland, the peoples of Yr Hen Ogledd (English: The Old North). It emphasised a perception that the Welsh and the ‘Men of the North’ were one people, exclusive of other peoples.

To understand better who Earl Gospatric was we need to understand a bit about the history of Britain from the time of the Anglo-Saxon advent up to and after the Norman invasion, particularly the history of the northwest of the country. Over time the Cymry (Welsh) had become cut off from their cousins in Cumbria, although undoubtedly many links were maintained by sea for centuries. Starting in around AD 600 the Angles under King Aethelfrith of Northumbria had started to make incursions into Cumbria, including into large tracts of what is now lowland Scotland.

Aethelfith conquered more territories from the Britons than any other chieftain of king, either subduing the inhabitants and making them tributary, or driving them out and planting the English in their places.

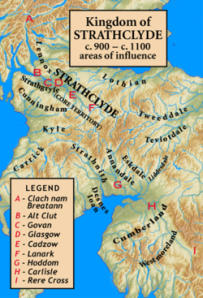

The Kingdom of Cumbria – Strathclyde

In ‘English’ Cumbria the Northumbrians did establish settlements but these were in general restricted to the lowlands and along the coast, they made almost no impression on the mountain fastness of the Lake District or in Galloway in the southwest of present-day Scotland. These areas were still predominantly the realm of the Kingdom of Cumbria, often referred to as the Kingdom of the Strathclyde Britons. Westmorland for example, where there was more Anglian settlement than in Cumberland, is an English word simply meaning ‘West of the Moors’, and the moors were the Pennines, over which the Angles had to come. The centuries-long battle for hegemony in the north of Britain involved three powers: the kings and later earls of Northumbria, the kings of Gaelic Alba (Scotland) and the kings of Cumbria (Strathclyde Britain). There were two other participants: the Norse-Irish Viking who started to arrive in this part of the world in the tenth century and the Gaelic Galwegians, who were feared as barbaric rapers, pillagers and general wreakers of havoc, until they were finally absorbed into Gaelic Scotland.

The borders of the kingdom of Cumbria ebbed and flowed – at one stage they possibly stretched from the Clyde all the way to Chester – mostly down the west coast of the British island but also in ‘Scotland’, including most of the Scottish lowlands.

Once the Norse-Irish Vikings has started to raid and settle in Cumberland they also started to make incursions and raids over the Pennines into English Northumbria and into Cumbrian regions in present-day southern Scotland. Shifting alliances continually fought each other for dominance. It was at least in part these Norse Viking raids that prompted the Northumbrians to try to get a better grip on Cumberland and Westmorland.

King Edgar at Chester in 973

The kings of Cumbria did eventually have to acknowledge their allegiance to the ‘West Saxon’ English king Edgar at Chester in 973. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded:

This year Edgar the etheling was consecrated king at Bath, on Pentecost’s mass-day, on the fifth before the ides of May, the thirteenth year since he had obtained the kingdom; and he was then one less than thirty years of age. And soon after that, the king led all his ship-forces to Chester; and there came to meet him six kings, and they all plighted their troth to him, that they would be his fellow-workers by sea and by land.

One of these kings was Malcolm, king of the Cumbrians, who together with King Kenneth II of Scotland, Maccus of the Isle of Man and several unidentified Welsh kings rowed King Edgar across the River Dee in Chester.

But Northumbrian and later English hegemony in Cumbria remained for a long time very incomplete, mostly nominal, and always contested by the Cumbrians themselves.

It’s a long and complicated history. I particularly recommend William E. Kapelle’s magisterial The Norman Conquest of the North and Tim Clarkson’s The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland. But let’s return to Gospatric, the Cumbric eleventh century earl of Northumbria. There are many questions; not least how a British Cumbrian chieftain became an English earl? Here are a few things we do know about Earl Gospatric:

In late 1067 Oswulf, the short-lived titular earl of Northumbria, was ‘killed by bandits’. Gospatric ‘who had a plausible claim to the earldom given the likelihood that he was related to Oswulf and Uchtred, offered King William a large amount of money to be given the Earldom of Bernicia. The King, who was in the process of raising heavy taxes, accepted’.

In early 1068 Gospatric joined with Edgar Atheling (the English claimant to the throne), Edwin earl of Mercia and Earl Morcar his brother, in an uprising against William the Bastard. They lost and Gospatric was stripped of the earldom.

William replaced Gospatric as earl by a Fleming called Robert Cumin (or de Comines). As I described in my article The Normans Come to Cumbria, this was to lead to another rising of the North of England, with the support of the Danish king Swein. Gospatric joined this too.

The Harrying of the North

King William heard of the revolt and, says Orderic Vitalis: ‘Swift was the king’s coming’, with ‘an overwhelming army’. Norman massacres ensued and William ravaged York and its church. Many of the English magnates escaped, including Gospatric, hopefully to fight another day. Annoyed with these pesky and rebellious Northerners, William committed regional genocide: the mildly named Harrying of the North.

In early 1070 Gospatric submitted himself to King William, who, interestingly, re-granted him the earldom. He remained earl until 1072 when William took the earldom away once more and gave it to Waltheof, Danish earl Siward’s son.

Gospatric fled to find refuge in ‘Scotland’, and for a time in Flanders, before returning to Scotland. The Scottish King Malcolm III Canmore (probably Gospatric’s uncle) then granted him the future earldom of Dunbar (Lothian).

Sometime shortly thereafter it is contended that Gospatric died. Chronicler Roger of Hoveden wrote:

Not long after this, being reduced to extreme infirmity, he sent for Aldwin and Turgot, the monks, who at this time were living at Meilrose (Melrose), in poverty and contrite in spirit for the sake of Christ, and ended his life with a full confession of his sins, and great lamentations and penitence, at Ubbanford, which is also called Northam, and was buried in the porch of the church there.

Details of Earl Gospatric’s death are debated. I’ll leave that aside for the present.

Bamburgh Castle

All historians are in agreement that it was because of Gospatric’s blood relationship (of whatever type) with the ancient earls of Northumbria, based on their castle of Bamburgh, that he was deemed eligible and acceptable to become earl of Northumbria, even if only for a few years. Certainly this relationship was with the Bamburgh earl Uchtred ‘the Bold’, who died around 1016.

Before going further we need to try to distinquish between several different Gospatrics (or Cospatrics). All were descended from Northumbrian earl Uchtred.

First there is Gospatric the third son of Earl Uchtred’s by his second wife Sige (daughter of Styr, son of Ulf). Unlike his two brothers Ealdred and Eadulf we know that this Gospatric never became earl of Northumbria; Simeon of Durham tells us this explicitly. It seems clear that this Gospatric was murdered in 1064 on the orders of Earl Tostig, King Harold’s brother, and that it was either his son or grandson Eadulf (‘called Rus’) who led the massacre of Norman Bishop Walcher and his men at Durham in 1080. From the date of his death and from the explicit statement of Simeon of Durham we know that this Gospatric was not the earl Gospatric, although some believe he might have been the Gospatric who issued the Cumbrian writ.

Next, Simeon of Durham is quite explicit that earl Gospatric was the son of Cumbrian ‘Prince’ Maldred (maybe even ‘King’) by his wife Ealdgith (Edith) of Bamburgh, the daughter of Northumbrian earl Uchtred and his third wife Aelfgifu, daughter of English King Ethelred ‘the Unready’. I concur with the bulk of Scottish and northern English historians in seeing this ‘earl’ Gospatric as being the issuer of the Cumbrian writ.

Thirdly there is a third Gospatric: the son of Sigrida and Arkil son of Ecgthryth. Sigrida is seen as being the daughter of Yorkshire thegn Kilvert who married Uchtred’s discarded wife Ecgthryth (daughter of Durham bishop Aldhun). This Gospatric was therefore also related to Earl Uchtred. There is much more to explore here but as it’s somewhat tortuous and even incestuous I’ll leave it for another time.

So it was assuredly his descent from Uchtred that legitimized Cumbrian Maldred’s son Gospatric becoming earl of Northumbria in 1068. To place Uchtred in a little context this is what William Hunt wrote about him in the Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900, Vol 58):

UCHTRED/UHTRED (d. 1016), Earl of Northumbria, was son of Waltheof the elder, earl of Northumbria, who had been deprived of the government of Deira (Yorkshire), the southern part of the earldom. Uhtred helped Ealdhun or Aldhun, bishop of Durham, when in 995 he moved his see from Chester-le-Street, to prepare the site for his new church. He married the bishop’s daughter Ecgfrida, and received with her six estates belonging to the bishopric, on condition that as long as he lived he should keep her in honourable wedlock. When in 1006 the Scots invaded Northumbria under their king, Malcolm II (d. 1034), and besieged Durham, Waltheof, who was old and unfit for war, shut himself up in Bamborough; but Uhtred, who was a valiant warrior, went to the relief of his father-in-law the bishop, defeated the Scots, and slew a great number of them. Ethelred II (968?–1016), on hearing of Uhtred’s success, gave him his father’s earldom, adding to it the government of Deira. Uhtred then sent back the bishop’s daughter, restoring the estates of the church that he had received with her, and married Sigen, the daughter of a rich citizen, probably of York or Durham, named Styr Ulfson, receiving her on condition that he would slay her father’s deadly enemy, Thurbrand. He did not fulfil this condition and seems to have parted with Sigen also; for as he was of great service to the king in war, Ethelred gave him his daughter Elgiva or Ælfgifu to wife. When Sweyn, king of Denmark, sailed into the Humber in 1013, Uhtred promptly submitted to him; but when Canute asked his aid in 1015 he returned, it is said, a lofty refusal, declaring that so long as he lived he would keep faithful to Ethelred, his lord and father-in-law. He joined forces with the king’s son Edmund in 1016, and together they ravaged the shires that refused to help them against the Danes. Finding, however, that Canute was threatening York, Uhtred hastened northwards, and was forced to submit to the Danish king and give him hostages. Canute bade him come to him at a place called Wiheal (possibly Wighill, near Tadcaster), and instructed or allowed his enemy Thurbrand to slay him there. As Uhtred was entering into the presence of the king a body of armed men of Canute’s retinue emerged from behind a curtain and slew him and forty thegns who accompanied him, and cut off their heads. He was succeeded in his earldom by Canute’s brother-in-law Eric, and on Eric’s banishment the earldom came to Uhtred’s brother, Eadwulf Cutel, who had probably ruled the northern part of it under Eric.

By Ecgfrida, Uhtred had a son named Ealdred (or Aldred), who succeeded his uncle, Eadwulf Cutel, in Bernicia, the northern part of Northumbria, slew his father’s murderer, Thurband, and was himself slain by Thurbrand’s son Carl; he left five daughters, one of whom, named Elfleda, became the wife of Earl Siward and the mother of Earl Waltheof. By Ethelred’s daughter Elgiva, Uhtred had a daughter named Aldgyth or Eadgyth, who married Maldred, and became the mother of Gospatric (or Cospatric), earl of Northumberland. He also had two other sons—Eadwulf, who succeeded his brother Ealdred as earl in Bernicia and was slain by Siward, and Gospatric. His wife, Ecgfrida, married again after he had repudiated her, and had a daughter named Sigrid, who had three husbands, one of them being this last-named Eadwulf, the son of her mother’s husband. Ecgfrida was again repudiated, returned to her father, became a nun and died, and was buried at Durham.

Earl Gospatric was certainly the son of Maldred, Simeon of Durham tells us and William Hunt agrees. But I believe there is another clinching factor in the identification of Earl Gospatric’s as the issuer of the Cumbrian writ: his many Cumbrian connections.

Maldred’s parents were Cumbrian ‘Thane’ Crínáin (Mormaer), Abbot of Dunkeld, and Princess Bethoc, the daughter of Scottish King Malcolm II. Maldred’s brother (and Gospatric’s uncle) was Duncan I (Donnchad mac Crínáin), who was killed by Macbeth, but who had became the first ‘Cumbrian’ King of Scotland via his descent from his grandfather the Scottish King Malcolm II. (It’s interesting to note that the chronicler Florence of Worcester later called King Malcolm III (Canmore) ‘the son of the king of the Cumbrians’. His father was Duncan I)

King Malcolm Canmore

The detailed genealogical arguments are lengthy and at times obscure; nothing is totally certain. But the important thing is that if the majority of historians are correct not only can Gospatric’s putative ancestry explain his link to the earls of Northumbria (and hence his title to the earldom) but also much of what we know of him and his descendants in later years. Gospatric’s father Maldred was probably born into a Cumbrian family (in its wider sense) in Dunbar in Lothian. He was certainly Lord of Allerdale in present-day northern Cumberland and might also for a time have been king of the Cumbrians. Gospatric himself was also ‘Lord of Allerdale’; it is clearly in that capacity that he issued his famous writ granting lands in Allerdale to his man Thorfinn Mac Thore. The lordship of Allerdale was to pass down in Gospatric’s family in the generations to come, firstly to his son Waltheof. Regarding Dunbar and Lothian, after his was stripped of his Northumbrian earldom by William the Conqueror in 1072, Gospatric was granted ‘Dunbar and lands adjacent to it’ by Scottish King Malcolm III (Canmore) – who was King Duncan I’s son and thus Gospatric’s cousin. This Lothian grant later became the earldom of Dunbar (or Lothian) and was passed to Gospatric’s son Gospatric II and then to his descendants. (It seems Gospatric’s daughter Ethelreda also married King Malcolm III Canmore’s son King Duncan II.)

So what we are seeing in the person of Earl Gospatric is a powerful lord of impeccable royal Cumbrian descent and credentials; also descended from and related to the Gaelic Scottish royal family as well as the Bamburgh earls of Northumbria, and even descended from English King Ethelred! He was a native British Cumbrian Prince (or at least an ‘earl’) whose family had held extensive lands in greater Cumbria (in the kingdom of the Strathclyde Britons) in pre-Norman Conquest days, perhaps for many generations.

Kenneth mac Alpin

There used to be, and unfortunately still sometimes is, a tendency in both English and Scottish historiography to regard events in the north of ‘England’ and in the south of ‘Scotland’ as being driven, in England, by English Kings and Anglian Northumbrian earls, with periodic interventions of Norse Vikings and Danish Kings. They interacted with ‘Gaelic’ Kings of Scotland – descendants of Kenneth mac Alpin. Through a long process and countless struggles the borders between England and Scotland were finally fixed roughly where they are today. This is a bit of a travesty of history. The native kings and people of Strathclyde Britain – the ‘Cumbrians’ – are either almost erased from history or seen as more or less ‘defunct’ by the eleventh century.

It’s only when we correct this aberration that we can really understand who Gospatric was. When we do so many of the things we know about him, and particularly of his descendants, start to be seen in a clearer light.

It has often been maintained that Gospatric’s position in Cumberland was owed to the Danish earl of Northumbria, Siward (Sigurd), who came to prominence as one of Danish king Cnut’s (Canute’s) strongmen in the region after Cnut had conquered Northumbria in the 1010s. In 1033 Siward became earl of York and in 1041/2 earl of Northumbria. In 1054 he defeated Macbeth. It has been suggested by William E. Kapelle that as part of the ongoing struggles for mastery over northern England and southern Scotland, Siward invaded Cumberland sometime before 1055, when he died. Was it then that Siward installed Gospatric in lands in Cumberland, including the lordship of Allerdale?

Now there is little doubt that Cumbrian Gospatric at some time owed allegiance to Earl Siward, this seems clear from the wording of his famous writ, regardless of its date and whether or not Siward was alive or dead at the time of its writing. He orders ‘that (there) be no man so bold that he with what I have given to him cause to break the peace such as Earl Syward and I have granted to them … ’. I reproduce this writ again in full:

Gospatric greets all my dependants and each man, free and dreng, that dwell in all the lands of the Cumbrians, and all my kindred friendlily; and I make known to you that my mind and full leave is that Thorfynn MacThore be as free in all things that are mine in Alnerdall as any man is, whether I or any of my dependants, in wood, in heath, in enclosures, and as to all things that are existing on the earth and under it, at Shauk and at Wafyr and at Pollwathoen and at bek Troyte and the wood at Caldebek; and I desire that the men abiding with Thorfynn at Cartheu and Combetheyfoch be as free with him as Melmor and Thore and Sygulf were in Eadread’s days, and that (there) be no man so bold that he with what I have given to him cause to break the peace such as Earl Syward and I have granted to them forever as any man living under the sky; and whosoever is there abiding, let him be geld free as I am and in like manner as Walltheof and Wygande and Wyberth and Gamell and Kunyth and all my kindred and dependants; and I will that Thorfynn have soc and sac, toll and theam over all the lands of Cartheu and Combetheyfoch that were given to Thore in Moryn’s days free, with bode and witnessman in the same place.

Allerdale

What I would like to ask, perhaps rhetorically, is this: Even if Siward had invaded Cumbria as Kapelle suggests, is it not more likely that Earl Siward was able to come to terms with a resident Cumbrian lord Gospatric, whose family had held the lordship of Allerdale, and no doubt other Cumbrian lands, for quite a long time? No doubt Gospatric’s family connections with both the ancient Northumbrian house of Bamburgh and the kings of Scotland helped as well? This is how I see it.

Of course I’ve not yet addressed the hoary question of the dating of Gospatric’s writ. Was it pre-Conquest or post-Conquest but prior to William Rufus’s arrival in Carlisle in 1092? I haven’t even addressed the question of whether the ‘Dolfin’ who was the lord of Carlisle in 1092 and who William Rufus expelled was Gospatric’s son? A view held by most but not all historians. Nor even have I examined when and where Gospatric was to die? I hope to return to these issues.

In the eleventh century present-day English Cumbria was neither predominantly peopled by descendants of Norse Vikings, nor unequivocally ruled by either the kings of England or the kings of Scotland. All of these had an important role to play to be sure, but the case of Gospatric makes it clear that the native Britons, the Cumbrians, were still there and in some cases still powerful; even though the heyday of their power had surely passed. It was only after the Normans really started to get a grip on the region under King Henry I that the Cumbrians finally make their exit from history

Sources and references:

Tim Clarkson, The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland, 2010; H. W. C. Davis, England under the Normans and Angevins 1066 – 1272, 1937; Archibald A. M. Duncan, Scotland: The Making of a Kingdom, 1975; Marjorie O. Anderson, Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland, 1973; William E. Kapelle, The Norman Conquest of the North, 1979; Ann Williams, King Henry 1 and the English, 2007; James Wilson, An English Letter of Gospatric, SHR, 1904; William Farrer, Early Yorkshire Charters, Vol 2, The Fee of Greystoke, 1915; John Crawford Hodgson , The House of Gospatric, in A History of Northumberland, Vol 7, 1901; James Wilson, A History of Cumberland, in William Page (ed) The Victoria County Histories; W G Collingswood, Lake District History, 1925; Edmund Spencer, The Antiquities and Families in Cumberland, 1675; John Denton, An Accompt of the most considerable Estates and Familes in the County of Cumberland (ed R S Ferguson, 1887); Sir Archibald C. Lawrie, Early Scottish Charters Prior to AD 1153, 1905; Marc Morris, The Norman Conquest, 2012; Roy Millward and Adrian Robinson, The Lake District, 1970; Richard Sharpe, Norman Rule in Cumbria 1092 – 1136, 2005.

Great blogpost – and thanks for recommending my book!

Thank you Tim. I’m still learning much from your book.

[…] Who was the ‘Cumbrian’ Earl Gospatric? […]

Do You know who was Dolfin son of Aylward? Who was Aylward and where did they come from?

While researching Count Alan Rufus of Brittany (before 1040 – 4 August 1093), I was surprised to learn that Gospatric’s heir Waltheof of Allerdale named his heir Alan.

I also wondered whether this Waltheof’s daughter Gunnilda of Dunbar (wife of Uhtred of Galloway) was named after Gunnilda of Wessex (King Harold’s daughter) who was alleged by Anselm to have abandoned the nun’s habit to live with Count Alan (and after 1093 with his brother Alan Niger), but Waltheof had a sister named Gunnilda. It seems plausible, unless there is proof otherwise, that Gospatric’s wife and Waltheof’s mother may have been named Gunnilda.

Between 1066 and 1088 Alan accumulated an English property portfolio extending from Southampton to the borders of Durham. Writing long after Alan’s death, Stephen of Whitby described him as a “friend”, distinguished not only by his great wealth but also by his high moral character.

Curiously, the famous Agnes of Dunbar bears the same name as Count Alan’s mother.

Gospatric had a daughter named Gunhildr, so the name was “in the family”. Besides, it was a popular name at the time.

However, the use of “Alan” would seem to be significant, as it was brought to England by the Bretons. The PASE (Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England) Domesday database shows that Count Alan Rufus was the protector and promoter of two out of the four native English lords to survive through 1086 as major landholders. One of these was a Thegn named Gospatric who was a tenant-in-chief of 44 Yorkshire manors and a tenant of Alan’s in another 19.

If the Thegn Gospatric was a relative of Earl Gospatric (perhaps his son of that name?), his heirs would have been grateful to well Count Alan, so that might explain why his name entered their family.

The thegn Gospatric who owned 44 Yorkshire manors was son of Archil, son of Ecgfith, and Sigrid, daughter of Kilvert, and Ecgfrida, who had been Ughtred’s first wife. Thus, this Gospatric was connected to the Cumbrian ones by marriage, but there is no evidence of a blood relationship, though this is averred by Harry Speight and J Horsfall Turner in their books on Bingley.

They also refer to him as ‘Lord of Bingley’, which indeed he was; but he was also Lord of many other places, in some of which he held much more land. I want to write more, but am unsure as to whether there is a limit, and am writing this on an ipad which doesn’t always do what I wish!

Sheila

I don’t think there is a word limit so write more if you wish.

Stephen

Sheila, are you citing the evidence in De Obsessione Dunelmi?

Searching on keywords in your comment above, I found a sample of Christopher J. Morris’s “Marriage and Murder in Eleventh-century Northumbria” in which he discusses the contents and provenance of the former, very interesting, document.

Morris’s analysis is very revealing of the complex family relationships between many different men named Waltheof and Gospatric – though the family tree Morris deduced lacks the names of many women who are known, such as Gunnilda of Dunbar.

However, the De Obsessione Dunelmi was evidently written too early to reveal why Earl Gospatric’s son Waltheof of Allerdale – out of the blue, as it were – chose the name “Alan” for his eldest son, so that remains a puzzle.

I have found Christopher Morris’s book invaluable, as I haven’t yet had a chance to look at the text of Symeon of Durham, though think it’s available in Surtees Society. I am currently trying to sort out the families descending from the Yorkshire Gospatric, including the Maude/Mohauts/Monte Alto family of West Riddlesden, who Sir Charles Clay misguidedly thought descended in the male line from Simon fil Gospatric

With regard to the name ‘Alan’: this name was used by the Yorkshire branch also, in at least two instances ie.

Archill/Gospatric/Ughtred/Thorfin/Alan (Ref. Early Yks Charters vol.1 no. 386)

Archill/Gospatric/Gospatric/Thorfin/Alan (Ref. EYC vol.1. 113—I think that’s the page number)

The Yorkshire Gospatric is descibed in domesdaymap.co.uk as “son of Arnketil”; I take it that Archill and Arnketil are variants of the same name, though I don’t understand the etymology.

It’s curious if Gospatric had two grandsons named Thorfin, both with sons named Alan.

Incidentally, a “Thorfin of Ravensworth” was a lord of many manors in north England in 1065 who was replaced in Richmondshire by “Bodin brother of Bardulf”.

A charter of Alan Rufus reputedly describes Bardulf as his Alan’s brother. However, I’ve read a genealogist’s claim that Bodin may have been Thorfin’s son and heir. Certainly a number of Alan’s tenants in 1086 were the sons of the lords from 1066.

The Bretons certainly had diverse names: Germanic (“William”, “Robert” and “Adela”), Hebrew (“Stephen” and “Samson”), Latin (“Musardus” and “Constance”), Iranian-cum-Celtic (“Alan”), Old British (“Brian”, “Conan”), Saxon (“Alfred”), and goodness-knows-what (“Enisant” and “Ribald”).

On another topic, if the House of Dunkeld’s claim of descent from the Dáirine of Ireland be true, then they were not technically Gaelic but rather Éireann, a pre-Gaelic people. My patrilineal surname, Driscoll (hEidirsceoil), is that of the senior line of the chiefs (Corcu Loígde) of the Dáirine. The tribe of the Dáirine are recorded as the Darini in Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia; at that time they dwelt in eastern Ulster (adjacent to their kin the O’Neill or Ua Néill) rather than the later Munster. The Dáirine claimed descent from one Dáire, which is Irish for Darios/Darius – it’s used in an Irish legend of Darius the Great. What a Persian/Medean name was doing in ancient Ireland I’ve no evidence, but at a stretch it might have a connection with Celtic historic memory: Brennus sacked Rome around the same time as Athens defeated Persia at the Battle of Marathon.

The Gaels came to Ireland in pre-Roman times from Galicia in northwest Spain, where Magnus Maximus was later born (on the estate of Count Theodosius); Magnus established the military base in Armorica that became Brittany.

In the early 1100s, during the tenure of Count Stephen of Tréguier (Landreger in Breton), who was Alan Rufus’s youngest brother and heir to the immediate family’s lands on both sides of the channel, there was an influx of Bretons to Scotland, especially to Ayrshire – for example, that branch of the descendants of Alan, the Seneschal of Dol, who would become the Stewarts moved north at this time. (The southern branch became the FitzAlan Earls of Arundel.) The Bretons integrated into Scottish society and intermarried with the Cumbrians and Gaels – linguistic affinities may have helped. This is around the time that the name “Alan” began to become popular: it would seem that both Alan Rufus and the future Stewarts influenced this phenomenon; the question is, in what measures?

I am interested in researching saxon landowners who continued to hold manors post conquest.

Their influence is greater than is generally believed particularly in the North.Have you looked at families other than Gospatric’s ?

Best we expand that to include Angles and native British, as the Saxon tribe didn’t settle the North. As indicated by Stephen, people of British-Angle-Norse descent were predominant across the north of England and through Scotland. Also holding large estates even in the south of England were the Scots of Irish (Eireann as well as Gaelic) descent, in particular King Malcolm III and his successors.

Much of my information is sourced from domesdaymap.co.uk and pase.ac.uk. They organise the Domesday data quite differently: domesdaymap details locations and holders one at a time, whereas PASE has a spreadsheet structure.

For the current purpose, PASE is the more immediately useful resource. From that one learns, for example, that pre-conquest, the owner of Wyken farm in Suffolk was named “Alan”. This seems so unlikely to some that they have proposed that the Domesday scribes misspelt an English name. However, I note that Wyken was a large holding, that one of Harold’s acts as King was to dispossess Norman and Breton lords of their English titles and properties, that in 1086 the holder was Peter of Valognes, that Peter’s sister’s name was Muriel (a strong hint of Breton ethnicity), and that all of Peter’s holdings were adjacent to Alan’s. It was quite common during the Norman period for holdings to be “adjusted”, and in 1086 the area around Wyken and nearby Bury St Edmunds formed a gap almost surrounded by Alan’s territory. That Alan was so sentimentally attached to Bury St Edmunds as to be buried there also seems significant.

Now, as to the immediate question, I’ve mainly looked at Count Alan’s impact on post-Conquest England (which was considerable, and in many ways – economic, political, educational, legal and linguistic – decisive to the future course of English history). Among his tenants, a notable survivor was Almer of Bourn, one of Edeva (Eadgifu) the Fair’s men. Keats-Rohan thinks he was a royal thegn, serving both Gyrth and Leofwine. This suggests that Almer was in the thick of the most intense fighting at Senlac (i.e. in the battle of Hastings). For an Englishman to survive that, I can only guess that he was swiftly captured. In 1065, Almer held 5 vills, and in1086, he held the same 5, plus another 4 vills. In 8 cases, the previous Overlord was Edeva the Fair, and in all cases the new Tenant-in-Chief was Count Alan. In one case, the previous holder was Lady Godiva and in another the Overlord had been Earl Alfgar. Perhaps Alan’s men captured Almer? I notice that Hardwin of Scales held property in many of these locations. Hardwin served Alan and was rewarded with some 80 manors as TIC, all very close to Alan’s Cambridgeshire properties.

An “Almer son of Goding” held land in 3 of the settlements where “Almer of Bourn” subsequently held, not the same plots (the old TIC of all 3 of the old plots was Earl Waltheof; their new TICs were Roger Montgomery and Eudo the Steward) but ones of equal or greater value. Among these locations, in Kingston, Longstowe Hundred, a 1065 lord was “Goding Thorbert, Edeva the fair’s man”, this strongly suggests that the two Almers were the same person, that he lost these properties when his old lord Waltheof fell from grace following the Revolt of the Earls in 1075, and that Count Alan compensated him for these losses.

Alan also gave two properties in Norfolk to “Almaer’s son”. (PASE spells Almer’s name with an “ae” ligature, which makes it very hard for me to search on).

“Medieval East Anglia”, edited by Christopher Harper-Bill, gives much detail on surviving landholders in that region, a number of whom were “Breton” Englishmen associated with Ralph the Staller and his son Ralph de Gael. Domesday evidence that Ralph the Staller received properties from Earl Gyrth suggest that he had a hand in Gyrth’s death at Senlac. So, perhaps it was Ralph who captured Almer, or maybe, Alan (and/or his brother Brian) and Ralph together, since Ralph and his son were Anglo-Bretons closely associated with Alan’s family: to wit, while holding English properties from his father, Ralph senior attested Breton ducal charters from King Canute’s time onward, and the exiled Ralph junior allied with Alan’s father Count Eozen the moment he landed back in Brittany in 1076.

It should be borne in mind that Bretons had been back in England since the reign of King Edward the Elder and that Alan Rufus’s cousin Duke Alan IV “Fergant” was a definite descendant of said king through his daughter Eadgifu of Wessex. Alan Rufus was a matrilineal descendant of Mélisende of Maine, whom a disputed genealogy claims was a female-line descendant of that Eadgifu.

Anglo-Saxons whom Alan retained included Beornwulf in Yorkshire, Ordmær in Cambridgeshire, Ealdræd in Yorkshire. Three properties in Suffolk formerly held by Edwin as a tenant of Edeva’s were given to Goding – apparently, Almer’s father also survived! Also, Grim in Yorkshire. Kolsveinn was retained in Cambridgeshire, Orm and Thor in Yorkshire, Thorkil in Norfolk and Yorkshire, and Wulfgeat in Norfolk.

I notice a “Gyrth count’s [Alan’s] man” in Quadring in Lincolnshire in 1086 – hmm! – and “Kolgrimr count’s man” held land in Lincolnshire.

Shelfanger in Norfolk was given to Modgifu, a free woman – Alan seems to have been fond (in a proper way) of the ladies, including the Conqueror’s wife and sister, and the feeling was evidently mutual.

There are several cases of a previous landholder’s property going to his son or sons, as in Yorkshire’s vill of Danby in Thornton Steward, held by Gamal in 1065 and given to his sons by 1086. Some of the other transfers from one Englishman to another look like they may have been from father to son.

You have obviously done quite a bit of research. Do you think there was a greater survival of pre conquest landowners in the north because many of them did not go south to Hastings after Stamford bridge and the northern lands were easier to control from the point of view of the new northern landowners by keeping the pre conquest landowners in place at least as tenants.

Several of the important families like the Nevilles seem to have anglo saxon roots.

During research of my own family I have come across a connection through my mother’s family with Archil or Arnketil son of Ulf who retained manors in Yorkshire.

Count Alan is interesting as he apparently developed relationships with several anglo saxon families which suggests some of the norman invaders were happy to work with the native population.

David, the “Reply button” has sporadic appearances, so I’ll reply to your previous post.

Firstly, a disclaimer: the info I’ve shared is always subject to revision and to the extent that it’s reliable it is a piecemeal sampling of better people’s hard work, and I thank them for their kindness in distributing the outcome of their scrupulous efforts via digitised networks.

“Do you think there was a greater survival of pre conquest landowners in the north because many of them did not go south to Hastings after Stamford bridge”

Quite conceivably so, as the Norwegians, in tandem with the deeply unpopular Tostig, had threatened the northern landholders directly, and why shouldn’t one Godwinson be used to beat back another? Whereas the south could look after itself, thank you. Moreover, there are obvious ethnic and personal reasons why Cumbrians, Bernicians and their extended British-Anglo-Danish kin might not be enthusiastic about risking their lives to save Harold’s own Sussex properties from a band of Norse-Breton invaders. Many, such as Gospatric, might feel a closer kinship to fellow Brythonic speakers such as Counts Alan and Brian and their followers, than to a southern Earl who had not consulted them before hastening to have himself declared King virtually over Edward’s still-warm body.

“and the northern lands were easier to control from the point of view of the new northern landowners by keeping the pre conquest landowners in place at least as tenants.”

William’s initial hope seems to have been that the whole of England would accept him as King once the usurper Harold was deposed, and things would continue as per normal with minimal changes. This meant that William’s men were supposed to settle for modest gains: lands of Edward, Harold, Gyrth, Leofwine and other deceased Earls and overlords were transferred, and those whom Harold had disposessed, such as Ralph the Staller, would have their lands and titles restored. (Why Alan was allocated all but one of Edeva’s estates in Cambridgeshire remains an open question.) When William left England in March 1067 for his triumphal tour of Normandy, all seemed to be going well.

Unfortunately, William’s regent in England, William fitz Osbern, and his appointed governor of southern England, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, were, from the English perspective, rapacious in the extreme, so it wasn’t long before trouble brewed. (Wiser and more sympathetic counsellors, such as Alan, were probably in Normandy with the King during all this.) By late 1067, the south of England was seething with resentment and rebellions broke out in Kent (surprise, surprise) and in Exeter.

“Several of the important families like the Nevilles seem to have anglo saxon roots.”

It’s impossible to disentangle the roots of old families! The Anglo-Saxons and the native British were in such close contact for centuries, and the ruling house of Wessex was founded by Cerdic, whose name is British not Saxon, as is the case with several of his successors. Anglo-Saxon, with all its Old Germanic complexity, seems to have become the official language of the elite across much of south and east England after several generations. Although there’s little record of how the common people spoke until shortly after the Conquest, I suspect that it was a simplified tongue. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle starts to be written in what we can recognise as Middle English suspiciously early in the Norman period, in my opinion.

The Nevilles have English, Breton and Norman antecedents. Their escutcheon bore evidence of many forebears; in the first quarter are the Beauchamp arms alternating with those of Thomas Beaumont, 1st Earl of Warwick. The latter is a chevron ermine on cheky azure and or (blue and gold), which are symbols of the Breton sovereign house – the “House of Rennes”, of which Alan Rufus was a member. Alan’s flag and livery seem to have been an ermine canton over azure and argent, as a son of Count Eozen who led what was then the cadet branch. One might object that heraldry was a later invention, but the Bretons carried on Roman military and vexillogical traditions which they innovated.

The Percy family, the long-time rivals of the Nevilles, were Bretons. For that matter, many of the “Normans” had deep Breton roots. Shameful to relate, Bishop Odo and Count Robert of Mortain seem to have been of Breton descent, as was Hugh of Avranches. “Norman French”, i.e. the dialect of Gallo that had absorbed some Norse words, was and is spoken only in limited areas of the Cotentin and parts of Upper Normandy. Even the civic politics of Rouen, the Norman capital, seems to have been dominated by Breton merchants, to judge by the situation in 1090 when William II called on them to rebel against Robert Curthose.

“During research of my own family I have come across a connection through my mother’s family with Archil or Arnketil son of Ulf who retained manors in Yorkshire.”

Very apposite! My grandparents’ male lines have various origins. Tobin is my step-great-grandfather’s name; it’s from Normandy but commemorates a Breton saint. My patriline is Driscoll, which is Eireann, specifically Dairine (children of Darius, if you please!); Claudius Ptolemy recorded this tribe as the Darini in what we’d recognise as eastern Ulster. My paternal grandfather was a Chapman; I think but have not proven that he descended from the merchant marine and banking family of Whitby who reputedly settled there among the first Angles to cross the North Sea: it’s said that they were already called “Chapman” way back around the year 400. My mother’s father was of the Kitchens of Cornwall, with a descent from the Carlyons who are connected by marriage to the Vyvyans and they to the Arundells. My maternal grandmother was a Tweed, and they came from Cheveley in Cambridgeshire, but are found elsewhere in East Anglia and also Yorkshire: Cheveley is interesting because it’s in the midst of the horse studs east of Newmarket, and Alan Rufus made his brother-in-law Enisant Musard of Plevin the lord of Cheveley and subsequently Enisant was Alan’s Constable of Richmond Castle. The Tweeds are really peculiar becuase they almost invariably are found where Alan had land, and self-identify as Celts, specifically as Welsh, which is really interesting because Alan’s patriline was from Vannes, which was settled from Gwynedd in Wales. After the Conquest someone renamed the Barwell river in Leicestershire as the “Tweed”; in Welsh the name means “family/kin/clan/people”; and the first Earl of Leicester was the brother of the Thomas Beaumont who used the Breton symbols, so it’s very intriguing.

“Count Alan is interesting as he apparently developed relationships with several anglo saxon families which suggests some of the norman invaders were happy to work with the native population.”

This was quite normal, especially for Bretons, of which several were named “Alfred”. Alan was interesting in so many respects: I’ve some 40 pages of precis about his chronology.

Ralph Banks is a survivor I had no idea existed until yesterday: look at this: http://domesdaymap.co.uk/name/410150/ralph-banks/

In 1065 Ralph had one property, in Orwell, Wetherley Hundred, Cambridgeshire, which he retained in 1086 under Guy of Raimbeaucourt as TIC. I found Ralph because Edeva and then Alan held another property in this settlement.

In 1086, Ralph Banks had an additional 7 properties: two in Pampisford (one formerly Almer’s under Edeva, but now shared between Ralph Banks and Ralph the Breton under Alan, and a second property now under the notorious Picot, Sheriff of Cambridge), one each in Kingston, Barrington and Whitwell, all under Picot, and two in Wratworth (one under Picot, the other under Guy of Raimbeaucourt).

Interestingly, Alan also had properties in each of those location; in most of them, so did Alan’s man Hardwin of Scales.

Earl Ralph de Gael (a Breton survivor until the Revolt of the Earls which he led in 1075) had a brother named Hardwin who forfeited his lands at the same time.

By contrast, there’s no record of Alan’s man (and 1086 TIC) Hardwin of Scales in 1065 Anglo-Saxon England, but he’s interesting in that over the centuries his family changed surname a couple of times: firstly to Smithson (the Smithsonian Institution was founded by James Smithson, an illegitimate member of this family).

The Smithson surname may be connected to Hardwin’s donation of the church of “Smethton Major” to Alan’s famous Abbey of St Mary’s in York. (See “The Archdeaconry of Richmond in the Eighteenth Century”, edited by L. A. S. Butler.)

In 1740, Hardwin’s male-line descendant Sir Hugh Smithson married Lady Elizabeth Seymour, the daughter of Lady Elizabeth Percy, last of the Percy bloodline. He then renamed himself Hugh Percy in order to keep that name extant. Sir Hugh became the Duke of Northumberland in 1766. The current Duke, Ralph George Algernon Percy, is Hugh’s male-line descendant. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_of_Northumberland.)

Alan was a mite sentimental. According to a local Sibton tradition, he not only gave the English manor of Sibton to his (and his brothers’ and sisters’) former wet-nurse Orwen, but when (some time before 1086) his chamberlain Mainard requested Orwen’s hand, with her manor, for his long service, Alan readily agreed. (Source: Page 50 of Domesday People: Domesday book, by K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, Boydell Press, 1999.) This indicates that Orwen was a widow. I guess that Orwen was born about 1020 and that Mainard was of similar vintage, so they’d have been in their 50s or 60s when they married.

Alan must have received a mighty boost in the esteem of the English in 1088 when he shared cause with them in utterly defeating and permanently exiling Bishop Odo of Bayeux, described by one of Orderic Vitalis’s sources as the chief oppressor of the English.

All of Alan’s major rivals for influence at court, such as Robert of Mortain, Roger of Montgomery, Roger Bigod and the Mowbrays/Montbrays, had supported the Bishop, so it seems likely that, as William II’s strongest loyal counsellor, it was Alan who persuaded the King to win the English over.

Geoffrey,

Arkil/Arkentil are names for the same man. Thorfin: Gospatric (of Bingley) had three grandsons named Thorfin, though only two of these, as far as I know, had sons named Alan. The third Thorfin was son of Dolfin: Arkil/Gospatric/Dolfin of Thoresby/Thorfin of Askrigg.

The maternal grandmother of these was a daughter of Dolfin, son of Thorfin, who I take to be Lord of Ravensworth. The Domesday Map co. designates him so, but PASE does not distinguish him. Pase spells his name both as Thorfinnr and Torfin.

Could this Thorfin be the same as Thorfin MacThore?

Christopher Morris in Marriage and murder…says that on Earl Siward’s Scottish expedition against Macbeth, he received support from ‘Dolfin, a Cumberland noble who died on the 1054 expedition. Dolfin’s family was allied by marriage to Arkil, the Yorkshire Lord who married Sigrid.’ Since Dolfin (or Dolgfinnr, as PASE has it) was holding land in Appletreewick, Hartlington and Rylstone in 1086, this does not add up. According to The annals of Ulster, the Dolfin who was killed was a son of Finntur.

On April 21st David Horsman asked about Anglo-Saxon landowners who continued to hold land after the Conquest. One useful source to be found in Yorkshire Archaeological Society Journal, vols. 4 and 5, is an article by Alfred S.Ellis : Biographical notes on the Yorkshire tenants named in Domesday Book. He lists many of these, and also gives some information about associated Norman overlords. Gospatric is said to have kept much of his land (sources vary as to exact amount), and to have retained even some of his disgraced father’s (archil/Arkentil), though he did have overlords, eg Alan of Brittany and Erneis de Burun.

David also mentioned Arkentil son of Ulf. I think he and Arkentil son of Ecgfrith are sometimes confused: Ulf’s son had 8 manors which PASE seems to link with the other Arkentil.

Sheila/Geoffrey

Thanks for the information I will have a look at the article when I next go to YAS.I find Open Domesday easier to follow than PASE

My Arkentil/Archil is the one with 8 manors and the family connection is that in Hampsthwaite Church is an 18th century memorial re William Simpson said to be descended from Archil. I appear to be related through my Mothers maternal line .

This Arkentil does not apparently have any link to Gospatric .

The Bradley, Hebden and Staveley families are supposed to claim connection with Dolfin and Gospatric. Is this Gospatric the Earl and is Dolfin the one who defended Carlisle against William Rufus ?

What is emerging is that statements like “the English landowners were replaced by Normans ” is inaccurate. A good many pre conquest owners continued to hold manors particularly in the North.

What do you make of the latest suggestion that the term “Waste ” does not mean abandoned but rather not surveyed ?

I will try to make a list of pre conquest owners who survived in Yorkshire and it would be good if we could cover the rest of England .

Actually David I would say that statements like “the English landowners were replaced by Normans” are very accurate. All these instances of English landholders holding on for a while (and usually only a while) are tiny in number compared to what happened to most.

Stephen

If you sort PASE Domesday entries by “Fiscal value” (tax) and compare this number with the “1086 value” (or with the “1066 value (text)” or the “1066 value (proxy)”), you will find many entries in which vills were esteemed capable of paying high taxes but paid no (recorded) rent to their 1086 tenant-in-chief (or 1066 overlord), while other vills paid high rents but no tax estimate was recorded.

Obviously, it matters a great deal whether the entries were simply blank or stated as nil paid.

In either case, it’s clear that the rents recorded as paid to the tenants-in-chief, were less than they might have received. So, either they did receive them but the amount was not recorded, or they chose not to take rent from those vills – the latter seems improbable.

If the amount was not recorded, then the Domesday survey was never completed. Is it because the clerks (and presumably the king) became distracted by more pressing matters, or because the people who knew the figures were absent? If the latter, where were they?

I’d like to know exactly which properties were stated as “waste”, and whether any of these correspond to the large discrepancies between tax and rent in Domesday. It would be especially interesting if properties in the same location had different status in regard to “waste”, tax and rent. (One might expect “waste” not to stop at a fence line inside the same village.)

In response to David’s query of 3rd May, about the Bradley, Hebden and Staveley families:

The Yorkshire Gospatrics

The Gospatric from whom descend the Hebden and Staveley families (and some say the Bradleys), was the Yorkshire one, son of Arkil/Arkentil, who had married a daughter of Dolfin, son of Thorfin, and whose sons were Ughtred of Alverston/Allerston (between Pickering and Scarborough, Dolfin of Thoresby, Gospatric, and, some say, Thurstan, but I know nothing of the last.

The younger Gospatric was said (by Symeon of Durham),to have ‘recently had to fight against Waltheof, son of Aelfsige (ie. Eilsi of Tees) This Waltheof was a great great grandson of Ecgfritha, first wife of Earl Ughtred. Gospatric was Ecgfritha’s great grandson (not Ughtred’s). The fight is thought to have been about the 6 vills given to Ecgfitha on her marriage by her father.

Waltheof’s parents, Orm and Aetheldrith, married after William came to England, (Wikipedia article on Earl Siward), so Waltheof could not have reached fighting age much before 1100, perhaps born circa 1085. Gospatric the younger is usually shown as the eldest of Gospatric senior’s children, but he seems to me more likely to have been the youngest, and there are other reasons to think this, which I must leave until later. I think of him as being born circa 1080.

Gospatric fitz Arkill’s residence is not known.He is often linked with Bingley, as Speight and Horsfall Turner were writing about Bingley and discovered that Gospatric held land there, TRE, but he held land over a very large area of Yorkshire, much of it in Nidderdale. Ellis, in Biographical notes on Yorkshire tenants named in Domesday (YAJ vols 4 and 5), says that ‘At Marton he had 12 carucates, the largest area held by him at any one place, and perhaps he had a hall there.’ In fact he had 12 carucates at Seamer, at Masham and at Horton, near Stamford Bridge. He had a manor at Allerston, which seems to have been taken over by his son Ughtred.

Ughtred’s son Thorfin, his wife Matilda de Fribois and their son Alan were involved in complicated arrangements with Rievaulx Abbey regarding their sheep, circa 1160.(Early Yorkshire Charters (EYC) vol.1 nos.384, 386, 387.) I must say here, that from what I have read of their land transactions, despite what has been written regarding the native landowners being under the Norman yoke, most of the Yorkshire descendants of Gospatric seem to have ‘carried on regardless’: perhaps just a Yorkshire characteristic?

CT Clay, in Early Yorkshire Families (YAS Record series) has a pedigree which shows Matilda de Fribois married to Thorfin fitz Dolfin, instead of his cousin Thorfin fitz Ughtred. The text gives the true facts, but unfortunately, the makers of the Hebden website give the wrong version of the pedigree.

Dolfin de Thoresby, son of Gospatric, (who had held Thoresby of Count Alan at the Survey), had Thorfin of Askrigg, (formerly held by Arkill) Ughtred of Ilton/Ilkton and Conistone, and Swain of Staveley. From Ughtred descended the Hebden family. His children all seem to have settled in the Craven area.

Swain had four sons and a daughter, Gonille, who married John de Morville. The name may be of interest to whoever posted a query about Gunilda a while back.Thomas of Staveley and his sons also had interests in Craven, as did Elias of Stainforth. There is much about them in EYC vols. 7 and 11. Robert son of Swain inherited Thoresby from his cousin Peter, son of Thorfin fitz Dolfin, who died childless.

Another source is Ellis:Notes on Ralph Thoresby’s pedigree. (Thoresby Society vol.4) This also has a faulty pedigree, showing Gospatric fitz Gospatric having a son, Thurstan, ‘whose son, Alan,exchanged land in Stanley, (i.e.North Stainley) near Ripon, with Archbishop Roger, 1173’. The name should be Thorfin, not Thurstan, and is correctly so in the deed. (EYC vol.1 p.113)

There are sites online which claim that the Bradley family descend from Gospatric. In 1066, a Dolfin, or Delfin, was joint Lord, with one Godwin, of Bradley, not the Craven one, but in Agbrigg, between Brighouse and Mirfield, which was a grange of Fountains. This Dolfin would seem to be the one whose daughter married Gospatric, and whose other lands lay in the Appletreewick area of Craven.

There are references to witnesses, Robert and Henry sons of Dolfin, and a daughter, Gila, at Bradley, circa 1170-90, in EYC vol. 3, and Fountains chartulary has references too. The Dolfin who had these children, from such dates as given,would seem to be of an age to be a son of Dolfin son of Gospatric, but there is no documentary evidence that he existed.

As for the Gospatric who should have fought Waltheof, I must leave him for another time.

Sheila wrote: “most of the Yorkshire descendants of Gospatric seem to have ‘carried on regardless’: perhaps just a Yorkshire characteristic?”

I fancy that Alan protected them. Earl Edwin’s former wealthy manor of Gilling in particular seems to have suffered badly from Odo of Bayeux’s depredations in 1069-70 and 1080, so by 1086 “the Land of Count Alan in Yorkshire” (Richmondshire) seems to have grown a virtual fence around it to prevent the Norman foxes from eating the English chickens. No Normans inside the boundary: only Alan, his merry men and the English.

Incidentally, I’ve read that Alan’s chief manor was Drayton in Lincolnshire, which included Boston. Under Alan and his successors, the Boston area became England’s second port, rivalling London. Customs duties records from King John’s reign show that by then the Wash ports collectively had became much busier than the Thames region.

Drayton was strategically well-positioned between Alan’s properties in East Anglia and those in Yorkshire, and also had river access to goods from the Midlands.

Which Staveley does this refer to?

Which Staveley does this refer to? Is it the Staveley near Knaresborough or the one near Sedburgh?

It is the one near Ripon I believe. Have a look at the Staveley family website which is quite informative.

It is Staveley near Knaresborough. The Staveley family papers are housed at Yorks. Archaelogical Soc. Many have been printed in Yas vol. 102 ( Yorks deeds vol.8) including two concerning the Simon son of Gospatric who Sir Charles Clay averred was Simon Maude. More information in the Fountains Abbey chartulary show that both the Simons were operating independently at the same time, and that Gospatric and his son Simon lived in North Stainley. This Gospatric was the son of the Domesday one

Look to Sheffield, Waltheof was the Lord of Ancient Hallam. William Peveril, the bastard son, of William the Bastard, was Sherriff of Nottingham. Peveril castle still looks over the old lead/silver mines of Castleton………….the old chase of Robin Hood.

Stephen, outstanding work! Would you know anything about Alphonsus Gospatric? Lord of Calverley? The Dunbars and historians do not know much if this is the son of Gos-Cospatric of Dunbar. Some say it is Dolfin? The reason being is that I noticed that a John Scott took his titles.

John, shares an interesting mystery with the Flemings! Anselm le Fleming, married Agnes of Dunbar and produced Richard Scott(origins of the Buccleuch Lines) and John Scott here married Alphonsus Gospatrics daughter. They reside in Yorkshire and held a title of Pudsley, linking them to Durham. Which would associate The Lord Lumley, this is the association of Walchers death! Lord Lumley’s son is Uchtred and his granddaughter is Lady Eschina who married the 1st High Steward and his half sister Avicia of Molle married Richard Fleming/Scot(father of the Buccleuch lines)! Lumley was married to the same princes that Maldred married before he wa murdered.

If this can be proven that Alphonsus Gospatric is from the Dunbar lines, this would allow added proof that John Scott who took the title is a direct cousin to Richard Scotts line of Flemings. Where, this allows the surname Scott to be rewritten in the UK!

Anyhow, your work is outstanding and it was one of the best I have read on the ancient lines of families! Thank you for the dedicated work to post all this information on Cospatrick!

kind Regards,

Gary Gianotti

Alphonsus Gospatric

Gary Gianotti asks about Alphonsus Gospatric, Lord of Calverley. William Paley Baildon, in ‘The Calverley charters’, has pertinent info. about Alphonsus. WPB was attempting to make a pedigree of the Calverley family, based on the work of Simon Segar, a seventeenth century antiquary who had charge of the charters, and who, according to WPB, had got them into a great muddle.

“I very soon found out that the pedigree and the charters did not fit and there were several serious discrepancies. There was nothing for it but to discard the old pedigrees altogether, and work out a new one on independent lines.”

He goes on,”The Calverley pedigree usually begins with one John le Scot who, (then he quotes Segar):’in all probability came into England with Maud, d.to Malcolm 3, K of Scots, who was mar. to Henry 1, K of England, and one of her courtiers.’ [W. Cudworth, in ‘Round about Bradford’ 1876, has it that the Maud in question was the Empress Maud, daughter of Henry 1.]

According to Segar,John le Scot is stated to have married ‘Larderina,second daughter and co-heiress of Alphonsus Gospatric, Lord of Calverley, Pudsey and several other manors.’ The names of the other two daughters are given as ‘Albania’ and ‘Charinthia’.

WPB says, “Even Segar was struck with the fact that these names looked a little suspicious, for he says,’Alfonsus being a modern name, it may be presumed that it is mistaken for Dolfin’, a suggestion more ingenious than convincing.” He goes on:

“I am disposed to think there may be a germ of truth in this story. The first of the Scots was clearly, from his name, a newcomer from the North, and his property in Yorkshire was most likely obtained by marriage. Now we learn from the Doomsday (sic) Survey that a manor, comprising 3 carucates in ‘Caverlei’ and ‘Ferselleia’ had belonged to one Archil in the reign of Edward the Confessor, and that after the Conquest this manor formed a unit in the great Lacy fee. The name of the undertenant at the date of the Survey is not mentioned.

Archil is a well-known man, and he and his son Gospatric certainly retained some of their Yorkshire property after the Conquest, but under the suzerainty of some Norman lord. Calverly,notwithstanding the silence of Doomsday, may well have been in the possession of the descendants of Archil in the middle of the twelvth century, and there is nothing inherently impossible, or even improbable, that an heiress of one of these married the first of the Scots.”

Baildon’s manuscript notes have been deposited at West Yorkshire archives in Bradford: a huge treasure trove, fortunately indexed to some extent. They include extracts from Dodsworth and similar sources, but also WPB’s own notes and roughly worked out pedigrees of the kind we all make, when attempting to make sense of things. These are clearly works in progress, where he has been asking himself ‘What if…’ or ‘Suppose…’

One such pedigree shows Archil (and his descent from Ecgfrith, here spelt Aykefrith), his son Gospatric and his children, including eldest son Gospatric. This younger Gospatric is shown with 6 children. The relevant thing here is that despite his scorn for Segar’s notion, he has chosen to use ‘Dolfin’ rather than Alphonsus, as the name of the father of the heiress who mar. John Scot.

From my own point of view, the most interesting thing about this pedigree is that it correctly shows ‘a dau., ux de Monte Alto,’ with a son, Simon de Monte Alto (who calls Adam fit Gospatric ‘avunculus’), and that he gives this daughter a brother, Simon, for I may as well declare my own interest in the whole Gospatric thing, which was to show that Simon Maude of West Riddlesden was not Simon son of Gospatric, as stated by Sir Charles Clay in Early Yorkshire families (and other sources), but an entirely different person. This interest, it now seems, was only the starting point for an ongoing investigation of Archil and his Yorkshire descendants, often confused with their Northumbrian kinsmen.

Alphonsus Gospatric

Gary Gianotti asks about Alphonsus Gospatric, Lord of Calverley. William Paley Baildon, in ‘The Calverley charters’, has pertinent info. about Alphonsus. WPB was attempting to make a pedigree of the Calverley family, based on the work of Simon Segar, a seventeenth century antiquary who had charge of the charters, and who, according to WPB, had got them into a great muddle.

“I very soon found out that the pedigree and the charters did not fit and there were several serious discrepancies. There was nothing for it but to discard the old pedigrees altogether, and work out a new one on independent lines.”

He goes on,”The Calverley pedigree usually begins with one John le Scot who, (then he quotes Segar):’in all probability came into England with Maud, d.to Malcolm 3, K of Scots, who was mar. to Henry 1, K of England, and one of her courtiers.’ [W. Cudworth, in ‘Round about Bradford’ 1876, has it that the Maud in question was the Empress Maud, daughter of Henry 1.]

According to Segar,John le Scot is stated to have married ‘Larderina,second daughter and co-heiress of Alphonsus Gospatric, Lord of Calverley, Pudsey and several other manors.’ The names of the other two daughters are given as ‘Albania’ and ‘Charinthia’.

WPB says, “Even Segar was struck with the fact that these names looked a little suspicious, for he says,’Alfonsus being a modern name, it may be presumed that it is mistaken for Dolfin’, a suggestion more ingenious than convincing.” He goes on:

“I am disposed to think there may be a germ of truth in this story. The first of the Scots was clearly, from his name, a newcomer from the North, and his property in Yorkshire was most likely obtained by marriage. Now we learn from the Doomsday (sic) Survey that a manor, comprising 3 carucates in ‘Caverlei’ and ‘Ferselleia’ had belonged to one Archil in the reign of Edward the Confessor, and that after the Conquest this manor formed a unit in the great Lacy fee. The name of the undertenant at the date of the Survey is not mentioned.

Archil is a well-known man, and he and his son Gospatric certainly retained some of their Yorkshire property after the Conquest, but under the suzerainty of some Norman lord. Calverly,notwithstanding the silence of Doomsday, may well have been in the possession of the descendants of Archil in the middle of the twelvth century, and there is nothing inherently impossible, or even improbable, that an heiress of one of these married the first of the Scots.”

Baildon’s manuscript notes have been deposited at West Yorkshire archives in Bradford: a huge treasure trove, fortunately indexed to some extent. They include extracts from Dodsworth and similar sources, but also WPB’s own notes and roughly worked out pedigrees of the kind we all make, when attempting to make sense of things. These are clearly works in progress, where he has been asking himself ‘What if…’ or ‘Suppose…’

One such pedigree shows Archil (and his descent from Ecgfrith, here spelt Aykefrith), his son Gospatric and his children, including eldest son Gospatric. This younger Gospatric is shown with 6 children. The relevant thing here is that despite his scorn for Segar’s notion, he has chosen to use ‘Dolfin’ rather than Alphonsus, as the name of the father of the heiress who mar. John Scot.

From my own point of view, the most interesting thing about this pedigree is that it correctly shows ‘a dau., ux de Monte Alto,’ with a son, Simon de Monte Alto (who calls Adam fit Gospatric ‘avunculus’), and that he gives this daughter a brother, Simon, for I may as well declare my own interest in the whole Gospatric thing, which was to show that Simon Maude of West Riddlesden was not Simon son of Gospatric, as stated by Sir Charles Clay in Early Yorkshire families (and other sources), but an entirely different person. This interest, it now seems, was only the starting point for an ongoing investigation of Archil and his Yorkshire descendants, often confused with their Northumbrian kinsmen.

Thank you for the insight into my families convoluted history. You have brought sense to a murky period in place and time. And also, I might ad, a sense of pride.

Hi could any one please help me, my name is darrell and I am a member of a group called Friends of Monk Bretton priory.The priory was founded in 1154 by Adam Fitz Swain son of Swain Fitz Alric I have been studying this family for quite sometime and it all seems to stop at Alric except for a tantalising snippet of information that comes from the history of Pontefract when we are told that William Camden says the first owner was Richard Ashenauld who had Alric who had Swain who had Adam.Now this Alric is identifiable as the Lord of Staincross wapentak he is probably of Danish decent. So how come he has a father probably born late 10th c. with a name like Richard Ashenauld.Also does anyone think there could be a family link to Arnbiorn of. Worsbrough, Healfden and Gamal son of Barth who are often linked together through land holdings two of Arnbiorns (Darton and Barugh) are both within half an hours walk from Alrics chief manor of Cawthorne not much of provenance I know but for such a powerful Thegn you would want someone who you could trust as your neighbours.Also these 4 thegns survived and held on to their lands albeit as. I D Ls tenants.Hope to hear from anyone soon thanks. Darrell

For the benefit of the general reader, the website of Darrell’s group, http://www.monkbrettonpriory.org.uk/, states:

“Adam Fitz Swain’s 12th-century priory of St. Mary Magdalene at Lundwood, Barnsley is also known as Monk Bretton Priory. It was a daughter house of St Johns Priory for Cluniac monks, founded by Ilbert de Laci (de Lacy) near to his base at Pontefract Castle.”

The Wikipedia page on the priory states: “In the course of time the priory took the name of the nearby village of Bretton”.

Presumably the village was so-named because of a post-conquest Breton settlement there, which would be an interesting matter to pursue, but returning to Alric’s family, in http://www.british-history.ac.uk/lancs-final-concords/vol1/pp54-74 we read, among many other facts:

” another portion of Wennington, Farleton and Tunstall, forming the greater part of the third estate, were held by Swain fitz Alric, together with other large estates in Cumberland and Yorkshire, presumably by grant from Henry I. He was a benefactor to the Priories of Pontefract and Nostel, and died before 1130, at which date his widow had been married to Hervey de Veceio (Pipe Roll, 31 Henry I.) His son and heir, Adam fitz Swain founded the Priory of Monk-Bretton, and died before 1159 (Pipe Roll, 5 Henry II.), leaving two daughters, (1) Amabel, the eldest, who married firstly Alexander de Crevequeur, and secondly William de Nevill, and had her purparty in cos. Cumberland, and Yorkshire, and a moiety of Croston cum membris, in co. Lanc., and (2) Matilda, who married Adam de Montbegon …”

Notice the “Nevill” connection. The Wikipedia article on the House of Neville cites J.H. Round for the following statement:

“Their Norman surname was only assumed four generations after the holder of 1129 — before which the male line was of native origin and had most probably been part of the pre-conquest aristocracy of Northumbria then including County Durham.[1: J.H. Round] The continuation of landowning among such native families was considerably more common in the more northerly parts of England than further south.[citation needed]

The family can be traced back to one Uhtred, whose son Dolfin is first attested in 1129, holding the manor of Staindrop (formerly Stainthorp) in County Durham …”

We’re not much closer to elucidating Alric’s ancestry, but we can affirm that, in considerable measure due to the influence of Count Alan Rufus and a long Scottish overlordship, the Cumbrian and other northern lords were retained in large numbers. One of the early Nevilles, a royal forester, was named Alan. King John had an adviser from this region named Alan of Galloway who was a grandfather of the Scottish king John Balliol and the great-great-grandson of Gospatric, Earl of Northumberland.

I am descended from a line of Bradleys to my Great Grandmother Abigail Bradley. There are male Bradleys in New Brunswick Canada who would have a y DNA directly to this time. If there are other families that could do this DNA comparisons to gospatric could be made.

I have written quite a long comment which amongst other things shows that the Gospatric from whom the Bradley family claim descent did not descend from the Northumberland Gospatrics, but now find I cannot paste it in. Help!

Sheila, may I suggest you safekeep your long comment in a text file on your computer or phone, then submit it in instalments, Charles-Dickens style?

I will re-type the whole thing, here goes:

The Gospatric from whom the Bradley family claim descent was the son of Archil, son of Ecgfrith. (Refs: Domesday, and Symeon of Durham) There is a pedigree in Speight’s Chronicles of ancient Bingley, which shows Archil as son of Ucghtred, 3rd earl of Northumbria, and shows no mention of Archil. The only link between the Yorkshire Gospatric and the Northumberland ones was via his maternal grandmothet, Ecgfrida, who was Ucgtred’s first wife, but the father of her daughter Sigrida, (who married Archil), was Kilvert son of Ligulf, Ecgrida’s second husband, so there is no blood connection to the earls here.

The Speight pedigree calls Gospatric ‘Lord of Bingley’, and so he was, but since he possessed so many other lands, he must have been lord of many other places, especially as he held more carucates in other places. It seems he must forever be stuck to Bingley in our minds because Speight and Horsfall Turner were writing about those places.

The pedigree gets one thing right at least, in showing Gospatric’s great grandson, Simon de Montalte (Maude), as son of the daughter of Gospatric junior. Her name was Matilda (Ref. Early Yorkshire Charters), and her husband (also named Simon de Montalte) is said by most antiquaries to be Simon, son of Gospatric. The two Simons, however, were two separate individuals. (Ref. Fountains Abbey Chartulary) But this is a diversion, so, returning to the Bradleys:

Gospatric, son of Archil, married a daughter of Dolfin son of Thorfin (Symeon of Durham et al) In 1066, Dolfin was joint Lord, with one Godwin, of Bradley in Agbrigg, between Mirfield and Brighouse, a grange of Fountains Abbey. In 1086 Ilbert de Lacy was lord. A Dolfin de Bradley, with offspring appears in the early 13th century (Ref. YAJ vol 29), and it is reasonable to suppose that he is a descendant of the daughter who married Gospatric, but where is the documentary evidence? It is known that Gospatric son of Archil had a son named Dolfin, but Dolfin’s sons, Thorfin, Ucghtred and Swein, are all well documented (Ellis: Notes on Ralph Thoresby’s pedigree, and see the Hebden family site)., and show no evidence of a Bradley connection. Without it, all is just guesswork. It is even possible that the 13th century Dolfin de Bradley descended from a hitherto unknown child of the Domesday Dolfin, thus bypassing Gospatric altogether. We know of only one ‘daughter of Dolfin’: the one who married Gospatric, but it is unlikely that she was an only child. A Dolfin de Clotherholme was active in the Ripon area, and I have sometimes surmised that his mother could have been another ‘daughter of Dolfin.’

If there is any evidence of a link between Gospatric and the Bradley family, I should be interested to see it.

I have been investigating the unusual use of the name Ecgfriþ for women. In her book Women’s Names in Old English, Elisabeth Okasha essentially cites two sources for such a name – the Latinized Ecgfrida (in the relevant case forms) in De Obsessione Dunelmi and an Old English manumission document added to the Durham Liber Vitae, which uses spelling “Ecferð”.

As you’re no doubt aware, De Obsessione Dunelmi contains two instances of a character Ecgfrida: Bishop Aldhun’s daughter discussed above, and a second Ecgfrida who was descended from the first Ecgfrida and Ucthred by this route, if I’m reading right:

Bishop Aldhun > Ecgfrida

Ucthred + Ecgfrida > Earl Aldred

Earl Aldred > Etheldritha

Orm (thane in Yorkshire) + Etheldritha > Ecgfrida

The Durham Liber Vitae manumission is Birch charter 1254 ( https://books.google.ca/books?id=Uv4UAAAAQAAJ&dq=cartularium%20saxonicum&pg=PA538#v=onepage&q&f=false ). Birch dates it to the late 10th century – I don’t know on what grounds. A scan of the original manuscript is also available via the British Library ( http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=cotton_ms_domitian_a_vii_fs001r ) – the text in question is on folio 47r.

Here’s my best attempt at a translation, since I haven’t seen a complete translation of the text elsewhere (it probably exists, but I haven’t seen it).

… gave freedom for the love of God and for the need of her soul – that is Ecceard the smith, and Ælstan and his wife, and all their offspring born and unborn, and Arcil, and Cole, and Ecferð Aldhun’s daughter, and all the people whose heads she received for their food in the evil days. Whoever changes this and deprives her soul of this, may God Almighty deprive him of this life and of the kingdom of heaven, and may he be accursed dead and alive forever to eternity. And she has also freed the people that she accepted from Cwæspatrik – that is Ælfwald and Colbrand, Alsie and Gamal his son, Eðred tread-wood and Uhtred his stepson, Aculf and Þurkyl and Ælsige. Whoever deprives them of this, may God Almighty be angry with him, and also Saint Cuthbert.

Some thoughts:

1. Cwæspatrik (or Cwæs patrike, as it appears in the dative form in the text) is evidently the same name as Gospatric. I wonder if this a relative of the Gospatrics in your post? Birch, in a footnote, guesses that he is an ancestor of the Earl Gospatric your post focuses on. He must have had a position of some power, to have transferred at least 9 unfree people to the author of the manumission.