One summer day in 1076 in present-day Ukraine a young English Princess called Gytha was giving birth to her first child. It was a boy. His Russian name was Mstislav, but he was also given two baptismal names as well, Harold and Theodore. Gytha’s husband was a prince of the Kiev Rus’, and prince of Smolensk, called Vladimir Monomakh (or Monomachus in Greek). He would later become the ruler and Grand Prince of a united Kievan Rus’, a huge area that stretched all the way from the Baltic in the north to the Black Sea in the south.

The death of King Harold

Although the ‘Russians’ referred to Gytha’s son as Mstislav, the Scandinavian and Germanic world used his baptismal name of Harold. This was in deference to, and recognition of, the boy’s maternal grandfather (and Gytha’s father) Harold, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, who had been slain and mutilated by William the Conqueror’s Normans at Hastings in 1066.

As I told recently (see here), it was in 1068, or possibly 1069, that many of Harold’s family had fled the tightening Norman yoke. They first went to the court of their kinsman Count Baldwin in Flanders, from where two of Harold’s sons, Edmund and Godwine, accompanied by their sister Gytha, moved on to find refuge with, and perhaps help from, their relative Swein Estrithson, the king of Denmark. Swein was King Harold’s cousin. Gytha, who was born around 1053, was named after her grandmother, who was Swein’s aunt

In The House of Godwine – the History of a Dynasty, historian Emma Mason writes:

Godwine and Edmund probably asked Sweyn for help in reinstating then in England. As an inducement they perhaps offered Sweyn their sister Gytha to use as a bargaining counter when he was negotiating some diplomatic alliance. Following the events of 1066-69, Gytha needed the help of an influential male kinsman to ensure that she made a marriage befitting a king’s daughter. Of her remaining kinsman, only Sweyn was in a position to assist.

The king was not prepared to offer his young cousins any military support. He had expended enough resources on his failed expedition of 1069 and had no wish to lose more in helping his kinsmen…. What actually became of these sons of King Harold is unknown.

Although there is no proof, Mason’s suggestion that, as well as seeking safety, the royal siblings were probably also hoping for Swein’s support in ridding England of the hated Normans, seems a reasonable one. If in fact the siblings had already arrived in Denmark by 1069, it could have been that their pleas helped prompt Swein to lead a large Danish army to England, which he did in the summer of that year. Swein certainly saw this as a chance for him to claim the crown of the Anglo-Scandinavian realm of England before William the Bastard and his Normans had too tight a grip.

A Danish Viking Ship

A huge Danish fleet, numbering between 240 and 300 ships, arrived in the Humber estuary where they joined forces with their English allies led by Maerleswein, Gospatric and Edgar the aetheling (the English claimant to the throne). The writer of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle at the time was ecstatic. The leaders set out, he wrote, ‘with all the Northumbrians and all the people, riding and marching with an immense host, rejoicing exceedingly’. Historian Marc Morris writes in his excellent The Norman Conquest: ‘The days of Norman rule in England appeared to be numbered.’ Unfortunately it was not to be. The Norman yoke was to be around English necks for centuries to come.

Cutting a rather long story short, William came back with an army to confront the Anglo-Danish force, but had then to retreat south to deal once again, as Orderic Vitalis tells us, with the resistance of ‘Eadric the Wild and other untameable Englishmen’. On returning to the North the only way William could find to defeat the Anglo-Danish army was to buy off the Danish. The Danish war leader Earl Asbjorn was offered a large sum of money to stop fighting, which, ‘much to the chroniclers’ disgust’, he accepted. After the Danish army had spent a desperate winter in England awaiting the return of King Swein, they returned to Denmark in 1070.

After 1070 Swein certainly wasn’t prepared to try his luck in England again, even though over the next few years several mores embassies arrived from England to plead for his help (for example see here). It seems that William continued to pay the Danes off. All hope for the young Anglo-Saxon princes, Edmund and Godwine, had passed. But, as Emma Mason suggests:

Gytha on the other hand was a useful asset to King Sweyn. Probably around 1074 or 1075 he arranged her marriage with Vladimir Monomakh, the prince of Smolensk in western Russia. From the prince’s point of view that was an advantageous match, giving him a wife who was a king’s daughter, and an alliance with King Sweyn against the Poles. From Gytha’s perspective, too, it was a good match. Prince Vladimir was young, rich and handsome.

Saxo Grammaticus

Whatever the precise circumstances and details, before his death in about 1075, King Swein did arrange for his young charge Gytha to be betrothed to the Kievan Rus’ prince of Smolensk, Vladimir. The early Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus wrote in Book 11 of his Historia Danica:

After the death of Harold, his two sons immediately fled with their sister to Denmark, Sweyn, forgetting the deserts of their father, as a relative received them under the custom of piety and gave the daughter in marriage to the king of the Ruthenians (Rutenorum) Waldemarus (who was also called Jarizlauus by his own people). He (Harold) obtained from the daughter a grandson who after the manner of our time became his successor both by lineage and by name. Thus the British and the Eastern blood being united in our prince caused the common offspring to be an adornment to both peoples.

Early Norwegian sources don’t mention the three siblings seeking refuge with Swein, but the Fagrkinna and Morgkinskinna both mention Gytha’s marriage to Vladimir. After telling the story of the death of King Harold Godwinson and his brothers, the Fagrskinna, which is a catalogue of the kings of Norway, goes on:

After these five chieftains there were no more of Jarl Gothini’s (Earl Godwin’s) family left alive, as far as we can tell, apart from King Haraldr’s daughter Gytha…. Gytha , King Haraldr’s daughter, was married to King Valdamarr (Vladimir), son of King Jarizleifr (Jaroslav) and of Ingigerthr, daughter of King Olafr soenski.

It then goes on to tell more of what became of Gytha and Vladimir’s children. The Morkinskinna tells much the same story.

Actually Saxo Grammaticus and the two Norwegian sources are somewhat confused here. Vladimir was the son of Vsevolod and not Jaroslav (who was his grandfather, and who died in 1052).

Under the year 1076, the Russian Primary Chronicle says, ‘in this year, a son was born to Vladimir, he was Mstislav, and was a grandson of Vsevolod.’

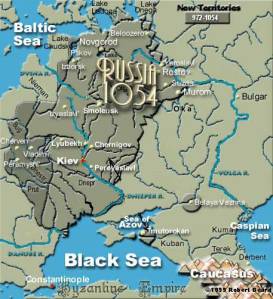

The extent of Kievan Rus’ in 1054

The world that Gytha had married into, that of the Kiev Rus’, was positively Byzantine in its complexity. The original Rus’ were Scandinavian Vikings, the Varangians, including a certain Rurik, who had been ‘invited’ to take control in the ninth century. Over the next two centuries the Rus’ extended their reach and control, but they were constantly fighting each other as well as their external enemies, usually the Poles. Kievan Rus’ became a series of fragmented princely territories. The continual feuding, intrigues and battles made pre-Conquest England seem somewhat stable by comparison.

Most likely Gytha and her young husband Vladimir were able to communicate in Danish. Vladimir, like his father Prince Vsevolod, is known to have spoken several languages, and Gytha, being a member of an Anglo-Danish family, the Godwins, likely spoke Danish as well as English. Emma Mason writes:

There were no problems of communication, since her husband was an accomplished linguist. His dynasty had Scandinavian origins and his grandmother was Swedish. Probably he could converse with Gytha in the Norse tongue.

While Vladimir and his father continued fighting, he and Gytha had several more children. Many of his children were later to be married into other princely families, as was the way throughout Europe. Mstislav/Harold followed his father in becoming Grand Prince of the Kiev Rus’ when Vladimir died in 1125. As both Norse and Russian sources tell us, Prince Harold married Princess Christina Ingesdottir of Sweden in 1095. Christina was the daughter of King Inge I of Sweden. Through his daughter Euphrosyne, Mstislav/Harold is an ancestor of King Edward III of England and hence of all subsequent English and British Monarchs.

But I’m concerned here neither with royal genealogy, nor with the history of Kiev and Russia, fascinating though both are. Rather this is the story of the Anglo-Saxon princess Gytha. What became of her?

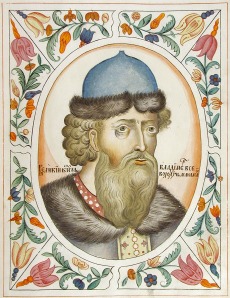

Prince Vladimir Monomakh

Conventionally it is said that Vladimir had three wives. But did he? As mentioned, the Primary Russian Chronicle mentions the death of two of his wives, under the years 1107 and 1126. We know that Gytha was Vladimir’s first wife, but who were the others? No names are found, just two dates of death. We know that Vladimir had several more children after the birth of Vyacheslav in about 1083. These children are usually assigned to an unknown putative second wife, who Vladimir is purported to have married after the death of Gytha. But there is no evidence whatsoever for the existence of this second, of three, wives: no name, no record of a marriage and no death. So it might very well be that these later children were Gytha’s as well?

That Vladimir did take another wife after Gytha seems reasonably clear, because, as mentioned, there are two entries for the death of a wife of Vladimir, in both 1107 and 1126. The name of this later wife who died in 1126 is often said to have been Anna, a daughter of Aepa Ocenevich, Khan of the Cumans, but there seems no evidence for this. It has been suggested that this attribution for the second/third wife most likely results from a misreading of the 1107 entry in the Primary Russian Chronicle, which states, “and Volodimer (Vladimir) took the daughter of Aepa for Jurij [his son]”. It clearly says that it was Jurij (who died in 1157) who married Aepa’s daughter, and not Vladimir. It’s unlikely that father and son married two sisters.

Returning to Gytha; what became of her and where and when might she have died?

In the German Rhine city of Cologne there was, and still is, a church and monastery dedicated to the late third century Greek Christian martyr St. Pantaleon, who was revered for his healing powers.

A man sick with the palsy was brought, who could neither walk nor stand without help. The heathen priests prayed for him, but in vain. Then Pantaleon prayed, took the sick man by the hand, and said: “In the name of Jesus, the Son of God, I command thee to rise and be well.” And the palsied man rose, restored to perfect health.

The monastic church of St. Pantaleon in Cologne

The monastic church of St. Pantaleon in Cologne was founded in the tenth century.

The impressive church, in the south west of the inner city, still has extensive parts of the original building. It is one of the oldest sacral buildings in Cologne. The monumental church of St. Pantaleon originated at the middle of the 10th century with the founding of a Benedictine abbey by the Archbishop Bruno. His niece by marriage, the Byzantine Theophanu, continued building after Bruno’s death in 965. Her interest in the church most certainly had family reasons, but especially the Patrocinium of the Holy Pantaleon played a decisive role, because this saint came from Theophanu’s homeland. Following her death she was buried in St. Pantaleon. Her mortal remains rest there today in a modern marble sarcophagus.

By the eleventh and early twelfth century it had acquired a certain international renown. It had strong links with England and also lay astride the usual route from Flanders to Denmark. Given later events, this latter fact has led some to conjecture that Gytha might have visited St. Pantaleon in Cologne with her brothers on her way to Denmark.

It is here we come to an interesting story. It’s contained in a Latin sermon given by Rupert, the abbot of the nearby monastery of Deutz, to the monks of St. Pantaleon’s in Cologne in the 1120s. Given the date of the sermon, the events it describes were certainly within the living memory of both Rupert and his audience, the St. Pantaleon monks. Most of the sermon was a hagiography detailing St. Pantaleon’s various miracles, but towards the end Rupert tells a little ‘miraculous’ story concerning Gytha and her son Harold. It’s a sort of prologue to two more miracles.

I have used the French summary of this Latin story given by the Belgian church historian Maurice Coens in 1937 in his Un sermon inconnue de Rupert, Abbe de Deutz sur St. Pantaleon. Coens’ summary unfortunately misses out some interesting details contained in the original sermon, and possibly misconstrues one or two things too, but for the time being it will have to suffice. The brackets are my own:

Harald, who reigns at present over the Russians (‘rex gentis Russorum’), had been attacked by a bear. He had been separated from his companions and, unarmed, couldn’t defend himself against the beast, which gored him cruelly. When he had been extricated, he was hardly breathing. His mother (‘Gida nomine’) wanted to care for him herself. But St. Pantaleon appeared (in a vision) to the wounded man, and declared that he had come to heal him. After she had heard of the vision, the prince’s mother was reassured regarding the health of her son. She had been a great benefactor of the monastery of St. Pantaleon in Cologne and knew the power of the thaumaturge (miracle worker). Following her son’s recovery, the Queen realised her desire to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Places.

In addition, there is also a mention of Queen Gytha (‘Gida Regina’ preceded by a cross) in St. Pantaleon’s Necrolog, under the date March 7th. This is usually taken to imply Gytha’s date of death, but this is by no means sure. No year is given because a Necrolog wasn’t only a list of those Saints and benefactors who had recently died; it was also a list of days on which the monks in the monastery were to say prayers for the eternal souls of particular saints and holy benefactors. As we know, Saints’ days aren’t necessarily death dates. Rupert’s sermon clearly tells us that ‘Queen’ Gytha was a ‘liberal benefactor’ of St. Pantaleon’s in Cologne. It was on March the 7th that the monks prayed for her, which could as well have been the date they heard of her death as her death date itself.

Vladamir’s Monomakh’s Instructions to his Children

The sermon tells us that Russian Prince (Rex) Harold had been badly gored by a bear while out hunting. We don’t know when this may have happened, such meetings with potentially dangerous wild animals were pretty common at this time when ‘nobles’ were out hunting, a time before Europe’s forests were completely hunted out. Harold’s father Vladimir was also a big hunter. He wrote some long ‘Instructions for my children’ (“Pouchenniya Dityam”) a few years before his death in 1125, in which he related his own experiences:

I devoted much energy to hunting as long as I reigned in Chernigov and made excursions from that city. Until the present year, in fact, I without difficulty used all my strength in hunting, not to mention other hunting expeditions around Turov, since I had been accustomed to chase every sort of game while in my father’s company.

At Chernigov, I even bound wild horses with my bare hands or captured ten or twenty live horses with the lasso, and besides that, while riding along the Ros, I caught these same wild horses barehanded. Two bisons tossed me and my horse on their horns, a stag once gored me, one elk stamped upon me, while another gored me, a boar once tore my sword from my thigh, a bear on one occasion bit my kneecap, and another wild beast jumped on my flank and threw my horse with me. But God preserved me unharmed.

Godfrey de Bouillon Captures Jerusalem

It has been suggested that Harold’s near death and vision happened in 1097, when he would have been about twenty-one, and, to make good on her promise to make a pilgrimage, his mother Gytha had then joined the First Crusade to the Holy Land, where she died in 1098. That Gytha went on the First Crusade seems highly dubious. It is pure speculation based only on the assumption that Gytha died before Vladimir’s later children were born – by a ‘second’ wife. To this is sometimes added the thought that Gytha had connections with Flanders, because of her stay there when she fled England, and that Flemish nobles, led by Godfrey of Bouillon, made up a large contingent of this crusade.

If we take Rupert of Deutz’s story at face value, as fact except for the ‘miraculous’ healing, then even if the incident took place in 1097 (for which there is no evidence), I find it unlikely in the extreme that Gytha would then have instantly rushed to Flanders to join some Flemish nobles on their crusade to a Holy Land still in the possession of the Saracens.

If Gytha did go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, as Rupert of Deutz says she did, I think it much more likely that she went later, after Jerusalem had fallen into Christian hands, by when it was safer to make such a hazardous journey. And if she wanted to get to Jerusalem she would likely have taken the well trodden route from the land of the Kiev Rus’ to Constantinople and from there taken ship around the coast of Anatolia (Turkey), perhaps via Cyprus, to the Holy Land.

Danylo’s Book

This was the route taken in the early 1100s by the earliest known pilgrim from Kievan Rus’, Danylo, abbot of the Rus’ monastery of Chernigov. Danylo has left us a fascinating memoir of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

It is not known when Danylo set out on his journey to the Holy Land. Historians are of the opinion that he could have begun his journey in the early 1100s and could have reached Constantinople at about 1104–1106 whence he proceeded to Palestine via Greece and the Greek Islands. It is not known by which route he got to Constantinople, but it is likely he took the ancient route “from the Varengians (Vikings) to the Greeks” — down the Dnipro River and then across the Black Sea.

He tells of the places he visited, the people he met (including King Baldwin of Jerusalem), and the hazards he encountered. He even mentions on more than one occasion that he was travelling with Kievan Rus’ compatriots:

In his book, Danylo mentions about 60 places, monasteries included, that he visited during his stay in Palestine. In his travels he must have always had some company in addition to guides and interpreters because he always says “we” and never “I”, and writes about “druzhyna” (a group, team, troop, or brotherhood who are united by the same purpose or sharing the same ideas and ideals) who were with him on many occasions. Describing “the descent of the blessed fire upon the Lord’s Sepulchre” he says that among the witnesses of this miracle were “all of my druzhyna, sons of Rus who were together with me on that day, good men from Novgorod and Kyiv — Izdeslav Ivankovych, Horodyslav Mykhaylovych, Kashkychi and many others…” It is quite reasonable to suppose that the people mentioned by name were Danylo’s close companions who were with him on many other occasions, or maybe accompanied him on his pilgrimage from the outset…

Danylo seems to be patriotically minded and it is particularly evident when he reiterates his being a representative of Rus rather than of a particular monastery or province. At the end of narrative, he says, “May God be a witness of … me never forgetting to mention the names of the Rus princes, and of their children, of the Rus bishops, and of the hegumens, and of the boyars (members of the aristocratic orders.), and of my spiritual children, and of all the good Christians [during the liturgy services] I recited at the holy places.” In the Holy Land he celebrated 90 liturgies — 50 for the living and 40 for the dead — of his compatriots.

There is, to be sure, no mention of Gytha here, but, for me at least, it would have made more sense had Gytha gone on her pilgrimage in the company of some of her compatriots, using the most convenient route, and when Jerusalem was already in Christian hands, than that she had rushed off to Flanders in 1097 to join the First Crusade.

It is also interesting to note that many Russian historians say that upon his return Danylo was promoted to bishop of Yuryev by ‘Grand Duke Vladimir Monomakh’, i.e. promoted by Gytha’s husband!

My contention that Gytha didn’t go on the First Crusade, and didn’t die in the Holy Land in 1098, is, I think, also supported by the thought that had she done so she would probably have had to drop in at St. Pantaleon’s monastery in Cologne on her way to Flanders, and there make a large enough, and one-off, benefaction to the monastery to ensure the reverence in which she was subsequently held by the monks there for her piety and largesse.

In addition, if Vladimir’s son Jurij was married to a daughter of Aepa Ocenevich, Khan of the Cumans, in 1107, as the Primary Russian Chronicle says, then Jurij was probably in his twenties at the time, and therefore born in the 1080s, well before Gytha’s supposed death in the Holy Land in 1098.

All the evidence seems to support the view that Gytha died in 1107.

St. Pantaleon/Panteleimon Church in Shevchenkove, Ukraine

The intercession of St. Pantaleon (St. Panteleimon) which had saved Prince Harold’s life was not forgotten by the Rus’. Churches named after the Saint began to appear all over the Ukraine. One such was built in the town of Shevchenkove in 1194 by Prince Roman Mstyslavovych in honour of his grandfather — the Kiev Prince Izyaslav (a son of English Princess Gytha born circ 1078, whose baptismal name was Panteleimon). There are several more.