When Winston Churchill was in the political wilderness he wrote. One of his first major works was a multi-volume biography of his ancestor John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough. In ruling circles John Churchill was a national hero. He, allied with the Austrians, had led the English army to a great victory over the French of King Louis XIV at the Battle of Blenheim in Germany in 1704. I won’t go into the details of the pointless War of the Austrian Succession, suffice it to say that John Churchill was amply rewarded with enough wealth not only to build Blenheim Palace but also to keep his family in luxury for the next three centuries. Winston Churchill grew up in Blenheim Palace and his inherited wealth enabled him to spend years researching and writing his histories as well as plotting his political comeback.

Man and Children from the Battle of Blenheim poem

Fascinating though both Churchills were, here I’d simply like to discuss one of my favourite poems written by the Lakeland poet Robert Southey in 1796. It is called After Blenheim or sometimes The Battle of Blenheim. (You can hear it read here by Derek Jacobi.)

It was a summer evening,

Old Kaspar’s work was done,

And he before his cottage door

Was sitting in the sun,

And by him sported on the green

His little grandchild Wilhelmine.She saw her brother Peterkin

Roll something large and round,

Which he beside the rivulet

In playing there had found;

He came to ask what he had found,

That was so large, and smooth, and round.Old Kaspar took it from the boy,

Who stood expectant by;

And then the old man shook his head,

And, with a natural sigh,

“‘Tis some poor fellow’s skull,” said he,

“Who fell in the great victory.“I find them in the garden,

For there’s many here about;

And often when I go to plough,

The ploughshare turns them out!

For many thousand men,” said he,

“Were slain in that great victory.”“Now tell us what ’twas all about,”

Young Peterkin, he cries;

And little Wilhelmine looks up

With wonder-waiting eyes;

“Now tell us all about the war,

And what they fought each other for.”“It was the English,” Kaspar cried,

“Who put the French to rout;

But what they fought each other for,

I could not well make out;

But everybody said,” quoth he,

“That ’twas a famous victory.“My father lived at Blenheim then,

Yon little stream hard by;

They burnt his dwelling to the ground,

And he was forced to fly;

So with his wife and child he fled,

Nor had he where to rest his head.“With fire and sword the country round

Was wasted far and wide,

And many a childing mother then,

And new-born baby died;

But things like that, you know, must be

At every famous victory.“They say it was a shocking sight

After the field was won;

For many thousand bodies here

Lay rotting in the sun;

But things like that, you know, must be

After a famous victory.“Great praise the Duke of Marlbro’ won,

And our good Prince Eugene.”

“Why, ’twas a very wicked thing!”

Said little Wilhelmine.

“Nay… nay… my little girl,” quoth he,

“It was a famous victory.“And everybody praised the Duke

Who this great fight did win.”

“But what good came of it at last?”

Quoth little Peterkin.

“Why that I cannot tell,” said he,

“But ’twas a famous victory.”

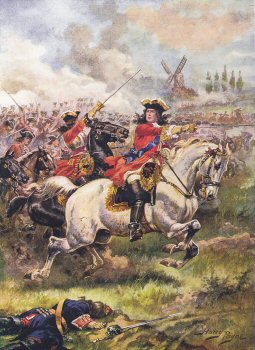

The Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Blenheim

It has sometimes been said that this is the first English anti-war poem, it isn’t but it is a wonderfully poignant piece. Its meaning is I think clear, it can’t be better expressed than it was by Rupert S. Holland in his Historic Poems and Ballard, published in 1912 in Philadelphia:

This battle was fought near the village of Blenheim, in Bavaria, on the left bank of the river Danube, on August 13, 1704. The French and Bavarians, under Marshall Tallard and Marsin, were defeated by the English and Austrians, under the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene.

The French and Bavarians were taken by surprise in the village, and their armies were badly handled. On the opposite side Marlborough and Prince Eugene showed themselves splendid cavalry leaders and led an attack that proved successful through its very recklessness. The French and Bavarians lost 30,000 in killed, wounded, and prisoners, while Marlborough’s loss was only 11,000. The battle broke the prestige of the French king, Louis XIV; and when Marlborough returned to England his nation built a magnificent mansion for him and named it Blenheim Palace after this battle.

Southey’s poem tells how a little girl found a skull near the battle-field many years afterward, and asked her grandfather how it came there. He told her that a great battle had been fought there, and many of the leaders had won great renown. But he could not tell her why it was fought or what good came of it. He only knew that it was a “great victory.” That was the moral of so many of the wars that devastated Europe for centuries. The kings fought for more power and glory; and the peasants fled from burning homes, and the soldiers fell on the fields. The poem gives an idea of the real value to men of such famous victories as that of Blenheim.

In this early period of his life Southey was a radical republican influenced by the great Thomas Paine and by the early optimistic years of the French Revolution. In 1794, even before he had written After Blenheim, Southey had written a ‘dramatic poem’ in three acts called Wat Tyler. As its name gives away, this was a play about the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. At the start of the play Wat Tyler and his friend Hob Carter are found in Tyler’s blacksmith’s shop in Deptford indignantly discussing the new ‘poll’ tax being imposed by the Crown to pay for its wars in France:

Hob:

Curse on these taxes – one succeeds another –

Our ministers – panders of a king’s will –

Drain all our wealth away – waste it in revels –

And lure,or force away our boys, who should be

The props of our old age! – to fill their armies

And feed the crows of France! Year follows year,

And still we madly prosecute the war; –

Draining our wealth – distressing our poor peasants –

Slaughtering our youths – and all to crown our chiefs

With Glory! – I detest the hell-sprung name.

Tyler:

What matters who wears the crown of France?

Whether a Richard or a Charles possess it?

They reap the glory – they enjoy the spoil –

We pay – we bleed! – The sun would shine as cheerly,

The rains of heaven as seasonally fall,

Tho’ neither of these royal pests existed.

Hob:

Nay – as for that, we poor men should fare better!

No legal robbers then should force away

The hard-earn’d wages of our honest toil.

The Parliament for ever cries more money,

The service of the state demands more money.

Just heaven! Of what service is the state?

Tyler:

Oh! ‘tis of vast importance! Who should p[ay for

The luxuries and riots of the court?

Who should support the flaunting courtier’s pride,

Pay for their midnight revels, their rich garments,

Did not the state enforce? – Think ye, my friend,

That I – a humble blacksmith, here in Deptford,

Would part with these six groats – earn’d by hard toil,

And that I have! To massacre the Frenchmen,

Murder as enemies men I never saw!

Didn’t the state compel me?

Watt Tyler leader of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381

When Southey wrote this in 1794 not much had changed in four hundred years: taxes were yet again being hiked to pay for another meaningless military escapade on the continent and ordinary young men in their thousands were literally being ‘pressed’ to serve in the army and in the Royal Navy. Wat Tyler wasn’t published until 1817 and then against Southey’s will. Unfortunately Southey had become a conservative reactionary and was appointed Poet Laureate in the same year as Wat Tyler appeared. He called the publisher ‘a skulking scoundrel’. As one contemporary critic put it, Southey was a poet until he became Poet Laureate! He wrote eulogies to the king and in 1820 referred to the Battle of Blenheim as ‘the greatest victory which had ever done honour to British arms’. Referring to Wat Tyler, Southey wrote:

The piece was written under the influence of opinions which I have long since outgrown, and repeatedly disclaimed, but for which I have never felt either shame or contrition. They were taken up conscientiously in early youth, they were acted upon in disregard of all worldly considerations, and they were left behind in the same strait-forward course, as I advanced in years.

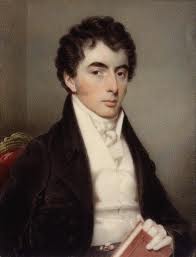

Southey had it fact sold out his youthful compassion and outrage. In his portrait of Southey in The Spirit of the Age William Hazlitt wrote: “He wooed Liberty as a youthful lover, but it was perhaps more as a mistress than a bride; and he has since wedded with an elderly and not very reputable lady, called Legitimacy.”

A young Robert Southey

Much has been written about Southey’s apostasy, my favourite is that of William Howitt in his Homes and Haunts of the Most Eminent English Poets, which he wrote in 1847, the year of Southey’s death:

With all our admiration of the genius and varied powers of Southey, and with all our esteem for his many virtues, and the peculiar amiability of his domestic life, we cannot, however, read him without a feeling of deep melancholy. The contrast between the beginning and the end of his career, the glorious and high path entered upon, and so soon and suddenly quitted for the pay of the placeman and the bitterness of the bigot, cling to his memory with a lamentable effect. Without doing as many hastily do, regarding him as a dishonest renegade; allowing him, on the contrary, all the credence possible for an earnest and entire change in his views; we cannot the less mourn over that change, or the less elude the consciousness that there was a moment when this change must have been a matter of calculation. They who have held the same high and noble views of human life and social interests, and still hold them, find it impossible to realize to themselves the process by which such a change in a clear-headed and conscientious man can be carried through. For a man whose heart and intellect were full of the inspiration of great sentiments, on the freedom of man in all his relations, as a subject and a citizen as well as a man, on peace, on religion, and on the oppressions of the poor, to go round at once to the system and the doctrines of the opposite character, and to resolve to support that machinery of violence and oppression which originates all these evils, is so unaccountable as to tempt the most charitable to hard thoughts. Nothing is so easy of vindication as a man’s honesty, when he changes to his own worldly disadvantage, and to a more free mode of thinking; but when the contrary happens, suspicion will lie in spite of all argument. We can well conceive, for instance, the uncle of the young poet, with whom he went out to Portugal, a clergyman of the Church of England, saying to him, “Robert, my dear fellow, these notions and these terrible democratic poems, — this Wat Tyler, these Botany Bay Eclogues, and the like, are not the way to flourish in the world. No doubt you want to live comfortably; then just look about you, and see how you are to live. Here are church and state, and there are Wat Tyler and the Botany Bay Eclogues. Here are promotion and comfort, there are poverty and contempt. Take which you will.” We can well conceive the effect of such representations on a young man who, with all his poetic and patriotic devotion, did not like poverty and contempt, and did hope to live comfortably. This idea once taking the smallest root in a young man having a spice of worldly prudence as well as a great deal of ambition, we can imagine the youth nodding to himself and saying, — “True, there is great wisdom in what my uncle says. I must live, and so no more Wat Tylers, nor Botany Bay Eclogues. I will adhere to the powers that be, but I will still endeavour to infuse liberal and generous views into these powers.” Very good; but then comes the transplanting to a new soil, and into new influences. Then come the hearing of nothing but a new set of opinions, and the feeling of a very different tone in all around him. Then comes the “facilis descensus Averni,” and the “sed revocare gradum hoc opus, hic labor est.” The metamorphosis goes on insensibly — “Nemo repent fuit turpissimus;” but the end is not the less such as, if it could have been seen from the beginning, would have made the startled subject of it exclaim, “Is thy servant a dog, that he should do this thing?”

Blenheim Palace