Court-centered history is not an adequate medium for recovering the past, even in England – William Kapelle[1]

So foreigners grew wealthy with the spoils of England, whilst her own sons were either shamefully slain or driven as exiles to wander hopelessly through foreign kingdom – Orderic Vitalis [2]

In King William’s twenty-first year (1087) there was scarcely a noble of English descent in England, but all had been reduced to servitude and lamentation – Henry of Huntingdon [3]

If the succession runs in the line of the conqueror the nation runs in the line of being conquered and ought to rescue itself – Thomas Paine ‘The Rights of Man’

After the Normans and other Frenchmen arrived in England in 1066, the chronicler of Evesham Abbey called them ‘ravening wolves’.[4] The near contemporary Shropshire-born Anglo-Norman monk and historian Orderic Vitalis said that they ‘mercilessly slaughtered the native people, like the scourge of God smiting them for their sin’.[5] In 1776 Thomas Paine wrote in ‘Common Sense’ that the invaders were a group of ‘armed banditti’ and that the ‘French bastard’ William was ‘the principal ruffian of some restless gang’. The Norman-French were and did all of these things. In this article I want to examine how and when these French ravening wolves arrived in what is now Lancashire, but was called then the ‘land between Ribble and Mersey’. It wasn’t until some years after the invasion of 1066, but still earlier than their arrival further north in Cumbria, which only happened in 1092.[6] Later I will provide a numeric analysis of south-west Lancashire, both before and after the Conquest, using the data and other evidence in Domesday Book. But to start with I’ll recap a little about the Norman Conquest and say something about Lancashire in the century or so before the French came to the area, and took it.

West Derby Hundred

You will notice that the title of this essay is ‘The French hostile take-over of Lancashire’ and not ‘The Norman hostile take-over of Lancashire’. At the time of the invasion and for centuries afterwards the new masters of the country always described themselves as French and saw themselves as being almost a separate species to the English, who they despised. Marc Morris tells us that in 1194 Richard the Lion Heart (Coeur de Lion) chastised some of his English troops saying: ‘You English are too timid’. Implying, says Morris, that ‘he himself was neither’.[7]

The Frenchman King Richard the Lionheart

In reading popular versions of English history, and even quite regularly more scholarly and learned works too, it is all too easy to forget a very significant fact: The armed Norman banditti who invaded England were French and they spoke French. Of course the Normans were originally North-men (Normands), they were Norse Vikings, but by the time of the conquest, while still retaining the brutal martial qualities of their Viking ancestors, they were thoroughly French and spoke one version of the many regional varieties of French in use at that time: Norman French. As more and more French men and women from other parts of France arrived in England throughout the late Middle Ages, the language spoken by the royal court, by the barons, by the local knights and in the courts of law slowly evolved and morphed – away from ‘Anglo-Norman’ and towards a more Parisian French. But let’s be quite clear: the conquerors continued to speak French as their primary language for a long time to come.

The English and their language were much despised, as indeed later on would be the Welsh, Irish and Scots as well. At the end of the thirteenth century, Robert of Gloucester could write:

And the Normans could not then speak any speech but their own; and they spoke French as they did at home, and had their children taught the same. So that the high men of this land, that came of their blood, all retain the same speech which they brought from their home. For unless a man know French, people regard him little; but the low men hold to English, and to their own speech still. I ween there be no countries in all the world that do not hold to their own speech, except England only. But undoubtedly it is well to know both; for the more a man knows, the more worth he is.

Of course there was a need for some sort of communication between the conquerors and the conquered. The native English needed to know some French if they had to serve and appease their new lords in their manors, work on the lords’ home farms or understand the lawyers and judges in the courts. Slowly but surely Old English or Anglo-Saxon evolved and morphed into Middle English, the language of Chaucer. Although French remained the principal language of the rulers, one by one, and at first very reluctantly, they started to be able to understand and then speak Middle English as well.

Of course there was a need for some sort of communication between the conquerors and the conquered. The native English needed to know some French if they had to serve and appease their new lords in their manors, work on the lords’ home farms or understand the lawyers and judges in the courts. Slowly but surely Old English or Anglo-Saxon evolved and morphed into Middle English, the language of Chaucer. Although French remained the principal language of the rulers, one by one, and at first very reluctantly, they started to be able to understand and then speak Middle English as well.

In 1362, Edward III became the first king to address Parliament in English and the Statute of Pleading was adopted, which made English the language of the courts, though this statute was still written in French! French was still the mother tongue of Henry IV (1399-1413), but he was the first to take the oath in English. That most ‘English’ of Kings Henry V (1413–1422) was the first to write in English but he still preferred to use French.

It is interesting to note that it was not until the days of Henry VII in the late fifteenth century that an English king married a woman born in England (Elizabeth of York), as well as the fact that Law French was not banished from the common law courts until as late as 1731.

When we read history books or watch television programmes about the exploits of ‘English’ kings such as Henry II, his sons Richard ‘Coeur de Lion’ and King John, or later about Edward I ‘Hammer of the Scots’ or indeed about the countless English barons and knights fighting each other as well as fighting the kings of England and France, it is advisable to remember that these people weren’t yet English in any real sense of the word and didn’t yet see themselves as such. Whether we call them ‘Anglo-Norman’ or something else, and whether or not they were born in England, these were all French aristocratic thugs.

I want to stress this linguistic and cultural point not because I have anything against the French, nor because there were only French thugs. Thugs in fact appear everywhere and their arrival on the historical stage is, rather sadly, one of the defining characteristics of our civilization itself. Rather, knowing what type of people these really were can help clear some of the mist from popular English history as it is too often presented, particularly about the ‘Norman Conquest’.

The Conquest

In the years immediately after the arrival in England of William the Bastard and his band of armed banditti, the part of north-west England that is today called Lancashire was of little concern to the invaders. It was quite literally beyond the edge of their known world. During the first five years of the occupation and colonization of England, William and his followers were fully occupied with dispossessing the English ealdormen and thanes of their land and divvying up the spoils between themselves.[8] They also had their hands full mercilessly putting down various English rebellions against their still shaky rule.[9] Some years later over in the Norman monastery of Saint-Evroult Orderic Vitalis wrote:

The English were groaning under the Norman yoke, and suffering oppressions from the proud lords who ignored the king’s injunctions. The petty lords who were guarding the castles oppressed all the native inhabitants of high and low degree, and heaped shameful burdens on them. For Bishop Odo and William fitz Osbern, the king’s vice-regents, were so swollen with pride that they would not deign to hear the reasonable pleas of the English or give them impartial judgement. When their men-at-arms were guilty of plunder and rape they protected them by force, and wreaked their wrath all the more violently upon those who complained of the cruel wrongs they suffered.

The Battle of Hastings

The dispossession of the English was, in the words of historian Robin Fleming in her magisterial and authoritative ‘Kings and Lords in Conquest England’, ‘a terrible slide towards annihilation’.[10] The whole process took many years and happened in a variety of ways. In a minority of cases Frenchmen were granted the estates of individual pre-Conquest English thanes, called antecessors. In many cases the king doled out whole tracts of territory bearing no relationship whatsoever to the holdings of particular pre-Conquest English ealdormen or thegns. In other cases the French just grabbed what they wanted without any authority from the king – they were exercising the rights of the conqueror, even if they were only among the ‘legions…. who were rushing across the channel to join in the scramble for worldly goods and riches’.[11]

Referring to England, Fleming comments:

The fields and copses, the livestock and peasants had all, before the Conquest, been controlled by an extensive aristocracy composed of perhaps four or five thousand thegns. The almost complete transference of all these lands, men and beasts in less than twenty years is astonishing… within twenty years of Hastings the overwhelming majority of land, with its vineyards, beekeepers and swine pastures, had been transferred from one lord to another.[12]

By the time the Domesday survey was taken in 1086, almost all of England was in French hands. The king had ordered the survey more to find out what his vassals actually held than for tax purposes, but it was certainly of use for that too.[13] The English aristocracy and most of the class of thegns had been completely destroyed. Some had died at Hastings in 1066, others during the rebellions in the north,[14] on the Welsh border or in the eastern fenlands,[15] while thousands more eventually despaired and left for Constantinople to join the Byzantine Emperor’s Varangian Guard.[16] Orderic wrote:

And so the English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off a yoke that was so intolerable and unaccustomed. Some sent to Swegn, King of Denmark, and urged him to lay claim to the kingdom of England which his ancestors Swegn and Cnut had won by the sword. Others fled into voluntary exile so they might either find in banishment freedom from the Normans or secure foreign help and come back to fight a war of vengeance. Some of them who were still in the flower of youth travelled into remote lands and bravely offered their arms to Alexius, Emperor of Constantinople, a man of great wisdom and nobility.

In ‘The Norman Conquest’, which I believe is the most balanced and thorough recent work on the Conquest, Marc Morris summed up the extent of the dispossession:

In ‘The Norman Conquest’, which I believe is the most balanced and thorough recent work on the Conquest, Marc Morris summed up the extent of the dispossession:

Of Domesday’s 1,000 tenants-in-chief, a mere thirteen are English… Whereas in 1066 there had been several thousand middling English thegns, by 1086 half of the land in England was held by just 200 Norman barons… but half of that half – i.e. a quarter of all the land in England – was held by just ten magnates.[17]

There were a few exceptions. Some thegns managed to hold on to bits of their former land for a while; although by now they were invariably mere tenants of new French barons and knights. We find examples all over the country in Domesday Book (DB). But when we catch sad glimpses of these pre-Conquest English landowners, still precariously hanging on as debased tenants, they are the exceptions to the rule. In the years following Domesday most of these survivors also lost what little land they had still clung on to in 1086. When we do find a case where a local pre-Conquest lord or thegn who actually prospered, as for example with the Norse named Forne Sigulfson in Cumbria – we are interested precisely because such things were so rare.[18]

The Norman Conquest had certainly brought about a ‘tenurial revolution’, in that the post-Conquest pattern of land ownership didn’t match that seen pre-Conquest. But much more importantly it had brought about a complete foreign occupation and colonization of the country, whose effects, it can be argued, are still to be felt today.

Tenth-century Lancashire

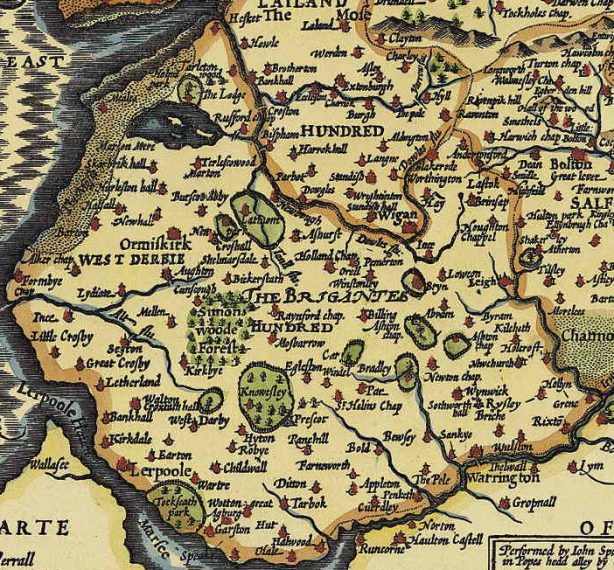

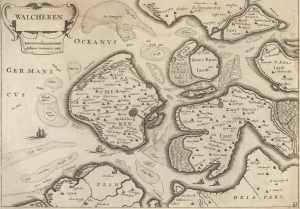

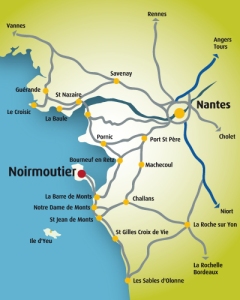

Our concern here is with Lancashire, which was called at the time ‘the Land between Ribble and Mersey’ – referring to the two rivers of that name.

The boundaries of this interesting and unique region were clearly defined by physical objects, the Mersey on the south, the Ribble on the north, and the Pennine range on the east, a western spur of this range which divides the watershed of the river Aire from the western Calder constituting a natural boundary on the north-east.[19]

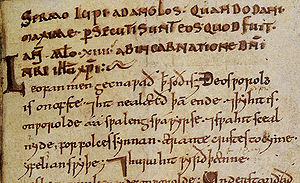

The first time we find use of the term between Ribble and Mersey was in 1002 in the will of a powerful Mercian English thegn (or perhaps he was an ealdorman) called Wulfric Spot. Wulfric held extensive estates throughout Mercia. His mother was Lady Wulfrun, who gave her name to Wolverhampton. In Wulfic’s will in 1002 he gave his lands betwux Ribbel & Maerse and on Wirhalum (Wirral) to Aelfhelm and Wulfheah. It has been suggested that Wulfric’s mother Wulfrun was the daughter of Wulfsige the Black, to whom King Edmund granted lands in Mercia in the early 940s.[20] It’s possible that Wulfsige the Black had also been given lands on the Wirral and across the Mersey by King Æthelstan after the pivotal Battle of Brunanburh, on or near the Wirral, in 937, or slightly later by his son King Edmund, who was reconquering the north in the early 940s. Perhaps these land grants north of the Mersey to Wulfric’s ancestor were part of the English kings’ attempts to take firmer control of these former Northumbrian lands now so heavily settled by Irish-Norse? It’s a subject worthy of more investigation.

Statue of Wolverhampton’s founder Lady Wulfrun

What type of land and society was the land between Ribble and Mersey in the tenth and eleventh centuries, before the Conquest and the French ravening wolves arrived in Lancashire? Unfortunately the whole history of north-west England during this period is obscure in the extreme. Yet we can say something.

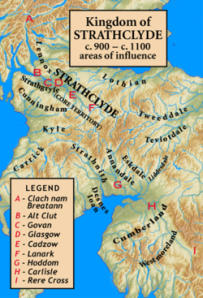

From the seventh century, Lancashire and Cumbria had been under the rule of the Northumbrian English.[21] In the eleventh century the population was still very sparse, but consisted of a considerable remnant of the Celtic British (the ‘Cumbrians’), many Northumbrian English settlers, plus, as Northumbrian power dwindled in the face of viking raids and Scots incursions in the late ninth and early tenth centuries, a heavy settlement of Irish-Norse.[22] In the early tenth century it is also likely that the Strathclyde Britons (called ‘the Cumbrians’ in English sources) started to reassert some of their former power south of the Solway Firth into northern Cumberland.[23]

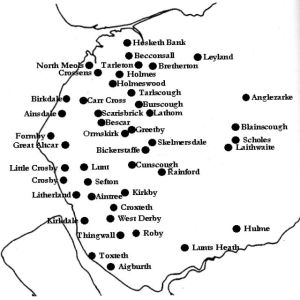

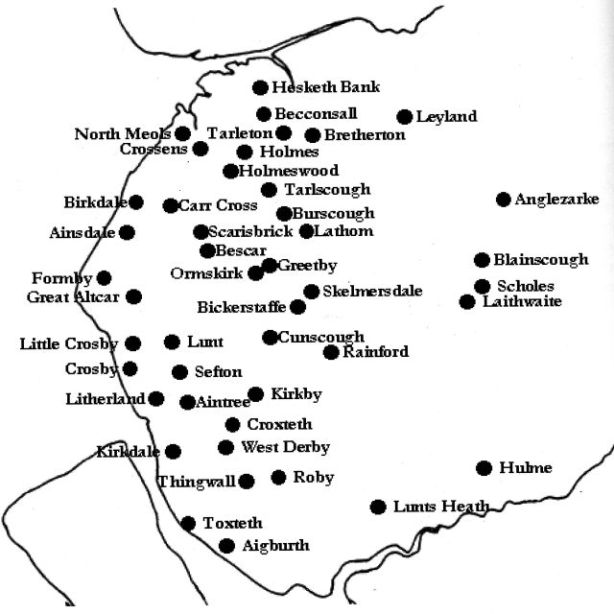

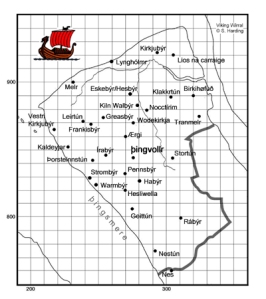

A few Norse place-names in West Derby Hundred, Lancashire

To restrict ourselves to Lancashire, the evidence clearly shows that sometime in the tenth century the whole of the Lancashire coast from the Wirral and the River Mersey in the south all the way up to Morecambe Bay in the north, was very heavily settled by Scandinavians who had originally come from Ireland following their temporary expulsion from Dublin in 902.[24] As the decades progressed, what were at first just a few coastal defensive bases for Viking fleets and warbands became permanent settlements and the Norsemen started to venture further inland – leaving their names in the landscape everywhere. Most, though by no means all, of our evidence for the Scandinavian settlement of north-west England, including Lancashire, comes from place-names, toponyms and other minor and field names. These have been extensively studied by generations of scholars, including Robert Ferguson, J. Worsaae, Eilert Ekwall and Frederick T. Wainwright, to name just four.[25] Wainwright wrote:

Finally it should be remembered that the influence of the Norsemen was not limited to conditions and events in the tenth century. We have seen how the new settlers left their mark on the racial complex, the social structure, the place-names, the personal names, the language, and the art-forms of Lancashire and the north-west. Their influence long outlasted the tenth century. It was a dominant factor in the history of Lancashire throughout the Middle Ages and it persists even today. As a mere episode the Norse immigration must be considered outstanding. But it was not a mere episode. It was an event of permanent historical importance.[26]

This much is beyond any doubt. The timing of the settlement and whether it was peaceful or not are other matters.[27] The Norsemen in north-west England still spoke a Norse language well into the eleventh and even into the twelfth and maybe thirteenth centuries, although as time went on their language merged with the English of their neighbours in specific locals.

Just because a particular clearing in the woods (a ‘thwaite’ in Norse, hence Thornythwaite, Dowthwaite, Crosthwaite etc) was clearly the work of Norsemen it doesn’t mean it was cut in the tenth century. It could have happened even centuries later. Nevertheless, even if a place or field name was coined later (particularly if it still shows correct Norse case endings, as for example in Litherland which preserves the Scandinavian genitive in ar) it still shows that the people of the area were speaking a form of Old Norse at the time.[28]

Putting these questions to one side, in my view the turning of the Scandinavians from raiding to settlement, farming and fishing probably really only got underway after the Battle of Corbridge on the River Tyne in 918 and after 920 when the Northumbrians, Danes, Norse and Welsh had recognized the authority of King Edward the Elder, possibly in Bakewell.[29]

The Battle of Brunanburh in 937

The grant of the whole of the northern Lancastrian district of Amounderness to the diocese of York by King Athelstan in 930, which we know he bought at a ‘high price’ (from the ‘pagans’ in one source), might suggest that the Scandinavians had already heavily settled this region by this time.[30] Even so, Edward’s son King Æthelstan still had to reassert his authority or supremacy over the various peoples of the north of Britain at Eamont Bridge in Cumbria in 927 and on the Wirral at the important Battle of Brunanburh in 937.[31]

Northumbrian power had by now completely vanished in the north-west and the Lancashire region was drawn more and more into the orbit and influence of the southern English kings. The possible history of Wulfric Spot’s holdings between the Ribble and Mersey might be one indication of this power shift – as undoubtedly is King Æthelstan’s grant of the whole of Amounderness in northern Lancashire to the diocese of York just mentioned.

Throughout the rest of the tenth century, and into the eleventh century, the racially mixed population of Lancashire settled down to eke out an existence from the soil and the sea, interrupted only rarely by larger events happening elsewhere.

The return of the Danes

King Cnut

The turn of the new millennium brought great new upheavals to England. These were precipitated by the return of the Danes late in the tenth century and, after much early rape and pillage reminiscent of earlier days, the eventual coming to the English throne of Danish king Cnut in 1028. I won’t retell the long and sordid history of this period.[32] Rather I would just like to highlight one upshot of the years leading up to the unexpected coronation of King Edward the Confessor in 1043. Robin Fleming, in ‘Kings and Lords in Conquest England’, has shown, among many other things, that during the later years of King Æthelred (‘the ‘Ill-counselled’ not the ‘Unready’), during the reign of King Cnut and during all the subsequent complicated and bloody fights between their sons and the Godwines, English aristocratic society was decimated to almost the same extent as was to happen again after the Norman Conquest. Vast numbers of English ealdormen and powerful thegns were slain; more were debased to become vassals of Godwine and the two other new Cnut-appointed earls, Leofric and Siward, and later the vassals of their sons and successors. During the reign of King Edward the Confessor the Godwinesons held more land than the king and far more than Leofric’s sons in the Midlands and the Siwardsons in the north.[33]

The original English aristocracy had been decapitated, a thing that without much doubt contributed to William the Bastard’s ability to subdue and colonize England so swiftly and so successfully after winning just one major battle.

Yet below these three powerful families and the king himself, there were still thousands of smaller English thegns occupying and working their lands with their ox-teams, villeins, bordars and slaves.

Pre-Conquest Lancashire

In Lancashire the families of Godwine, Leofric and Siward held no lands at all just before the conquest. In the ‘time of King Edward’ (TRE) i.e. in the years leading up to 1066, Domesday tells us quite a lot about what it lists as the ‘land between Ribble and Mersey’ (Inter Ripam et Mersam). There were six hundreds included in this region: West Derby, Warrington, Newton in Makerfield, Salford, Blackburn and Leyland. I’ll concentrate of the most south-western of the six hundreds lying between Ribble and Mersey: that is the hundred of West Derby. This is an area stretching up the coast from present-day Liverpool on the Mersey to Penwortham, just south of Preston on the River Ribble, and some way inland too. The caput, or capital manor, of the hundred was situated at West Derby itself. The reason I choose to highlight West Derby is in the first instance because it is both the best documented hundred in Domesday Book as well as being the most heavily populated hundred in Lancashire. In addition, one of my concerns here, as elsewhere, is to explore the history of the Norse settlement of north-west England. It is in West Derby Hundred that the Irish-Norse settled in the greatest numbers.[34]

Let me draw attention to one peculiarity of the Domesday entries for Lancashire (which are included under Cheshire). In 1899 William Farrer wrote in ‘Notes on the Domesday Survey of the land between Ribble and Mersey’:[35]

One feature to be here noticed is that the six hundreds into which this district was divided were treated as manors, having their respective mansiones or manor-houses at West Derby, Warrington, Newton, Salford, Blackburn, and Leyland… The explanation is to be found in the fact that this district fell into the hands of the Crown by conquest, and was populated by a class of half-free tenants, called thanes and drenghs, whose status was, with few exceptions, little above that of the villeins. Now the collectors of Danegeld did not care to deal with many half-free taxpayers, especially when the taxpayers owed suit and service to some lord of high estate. In this district in Saxon times that lord was the king, and so the geld was charged against his great manor-houses of West Derby, Warrington, Newton, Salford, Blackburn, and Leyland, and the men whose berewicks or sub-manors lay in their lord’s greater or capital manor had to bring thither their rent, to resort thither for legal redress, and also to bring thither their contribution to the Danegeld, and the lord was held responsible to the collectors for the whole… [36]

Now the dependency of the berewicks and sub-manors between Ribble and Mersey upon six great manors, and the obligations of suit and service to be performed by the tenants at the six capital manor-houses, explains the scantiness and bareness of the details collected by the Domesday commissioners within this district. The king himself being lord of the whole, no more details than those recorded were required.

Actually there was another reason for the scantiness of the information collected. Elsewhere Farrer suggested that the Domesday commissioners had never visited the areas of northern Lancashire and the Pennines, included under Yorkshire. I would strongly concur. When we look at the Domesday entries for between Ribble and Mersey it looks to me that the commissioners had possibly only visited the capital manor of West Derby, it being only a short ride from the Norman earldom of Cheshire. I tend to agree with Andrew Gray, who in ‘The Domesday Record of the Land Between Ribble and Mersey’ wrote:[37]

Judging from the scantiness of the information, it would certainly seem as if the Domesday Commissioners had contented themselves with crossing over from Chester to the king’s manor of Derby, and there had gathered sworn information about that Hundred, and gleaned further pieces of knowledge about the five other Hundreds (especially about the king’s land in them), without troubling themselves to penetrate into a part of the country so wild and desolate, and inhabited by people full of a sturdy independence.

I would like to draw attention to one other feature of the Lancashire Domesday. Unlike in the rest of Cheshire and much of the rest of the country, in the entries for between the Ribble and the Mersey, and most noticeably in West Derby Hundred, more detail is given about the ownership of the various manors before the Conquest than about the situation in 1086. Just by way of example, we might compare the entry for Halsall in Lancashire with Newton in Cheshire. The entry for Halsall reads:

Ketil held Halsall. There are 2 carucates of land. It was worth 8s.[38]

In Cheshire the entry for Newton (in Middlewich Hundred) reads:

Joscelin holds of Earl Hugh Newton. Gruffydd held it and was a free man. There is 1 hide paying geld. There is land for 3 ploughs. In demesne is 1 (plough) and a oxman. A priest with 1 bordar has 1 plough. There is an acre of meadow. TRE it was worth 4s, now 10s.

In West Derby Hundred we know that in 1086 Roger de Poitou had until recently held everything (as he did the rest of Lancashire), and we find the names of some of his French henchmen holding of him. But which lands his French vassals held is nowhere stated – although attempts can be and are made to find out.

Pre-Conquest land and manors in West Derby Hundred

I will try to summarize the situation in the hundred of West Derby in the run up to the Conquest. As we have seen, the region was settled by a mixture of Norse and English. There were no doubt some genetic descendants of the original British still there too, but by this time they would be culturally and linguistically indistinguishable from their Germanic neighbours. The area was, as we will see, very sparsely populated, but following the upheavals and settlements of the tenth century, West Derby was by 1066 a rather peaceful, though poor, backwater.

An ‘Anglo-Saxon’ village

In an ‘Introduction to the Lancashire Domesday’ in the ‘Victoria County History of Lancashire’,[39] and also in the earlier article I referred to before, William Farrer undertook some numerical analysis based on the Domesday entries. Rather than use these I decided to do my own statistical analysis, and thus unless otherwise stated all the numbers I use below are my own. They differ only slightly from Farrer’s but address different questions.

According to my calculations there were 113 ploughlands (carucates) in West Derby Hundred in the time of King Edward. They were spread over 60 manors – if we include the capital manor of West Derby itself, held by the king. On average about two ploughlands per manor. In Lancashire an ‘oxgang’ (1/8th of a ploughland) averaged fifteen statute acres, and thus the pre-Conquest hundred of West Derby comprised 13,560 statute acres of arable land. This equates to 21.18 square miles or 54.64 square kilometres. To put his in perspective this total is only about one half of the present surface area of the city of Liverpool (112 square kilometres). Of course not all the land being cultivated would have made it into Domesday, particularly many smaller or remote plots falling ‘below the radar’. There was, no doubt, some unrecorded upland sheep farming as well. Other economic activity would have included fishing in the Irish Sea and in the rivers and meres of the area. Nevertheless, West Derby Hundred wasn’t very heavily farmed in the times around the Conquest.

Distribution of land ownership

Although the average arable land per manor was around two, the distribution was highly skewed.

The king’s caput manor of West Derby and its six satellite berewicks[40] totalled 24 ploughlands i.e. 21% of the total in the hundred. He had woodland and hawk eyries as well, if he ever wanted to go hunting – although it is doubtful that the king ever visited. There is only one other major local landowner called Uhtraed (Uchtred in DB). Uhtraed held 17 of the 60 manors in the hundred, with 30.25 ploughlands – more than the King’s capital manor and 26% of the total in the hundred. So the King and Uhtraed combined held nearly one half of all the land in West Derby Hundred before the Conquest.

No pre-Conquest names are given for thegns in 28 of the 60 manors in the hundred. For example for Allerton we read: ‘Three thegns held Allerton as 3 manors…’ After the King and Uhtraed only 13 other thegns are named: Beornwulf, Stenulf, Dot, Æthelmund, Wynstan, Almaer, Aski, Wulfbert, Lyfing, Wigbeort, Godgifu, Teos and Ketil.

These 13 named minor thegns held 14 (23%) of the 60 manors (only Stenulf held 2), with 1, 2 or 3 ploughlands each. Dot exceptionally holding 6 in Huyton and Tarbock. They held 30.4 of the total 113 ploughlands in the hundred, or 26%, with an average of 2.33 ploughlands each. These men were still quite minor thegns, but they were at least significant enough to be recalled by the jurors twenty years after the Conquest. Some of them might even have been jurors.

Finally, we come to the 37 unnamed thegns (including 4 radmen). If we assume that they were all separate people (which might not be so unreasonable a suggestion given their geographic distribution), then these 37 unnamed small thegns held 28 manors. As we see in Domesday many single manors were farmed by several thegns. They held 28 ploughlands between them, i.e. on average one ploughland each and 25% of the total farmed arable land in West Derby Hundred.

While it is clear that pre-Conquest landholding in this part of Lancashire was highly concentrated in the hands of King Edward and one powerful local English lord called Uhtraed, we might make a couple of additional observations. Over one half of the land was still farmed by small independent Anglo-Norse farmers; 79% if we include Uhtraed. The King was, of course, an absentee landowner and his important desmesne of West Derby with its six berewicks would also have been farmed by some people who would have amounted to small local thegns in their own right.

As we will see later this situation would change radically after the Conquest.

Geographic spread of the manors

The next thing worthy of comment is that the vast bulk of the manors in West Derby, both before and after the Conquest, were in or extremely close to the modern city of Liverpool. These manors included not only King Edward’s capital manor of West Derby and its six berewicks[41] but also the majority of Uhtraed’s manors too, as well as the holdings of most of the lesser thegns. There were just a few manors lying to the north along the coast towards the Ribble and some slightly inland: in places in and around Ainsdale, Formby, North Meols, Skelmerdale, Halsall, Lathom and Scarisbrick.

Norse settlement was particularly dense around North Meols (Southport)

Identity and ethnicity of the pre-Conquest thegns

It has already been notes that if we exclude the king there were 51 thegns in pre-Conquest West Derby Hundred, but only fourteen of these are named: Uhtraed, Dot, Stenulf, Beornwulf, Wynstan, Almaer, Aski, Æthelmund, Wulfbert, Lyfing, Godgifu, Teos, Ketil and Wigbeorht.

They were obviously a mixed bunch with both English and Norse heritage. William Farrer wrote:

The combination in this county of Northumbrian, Mercian, and Danish place names, to which so long ago as 1801 the historian, Dr. Whitaker, called attention, bears witness to the intermixture of languages; of the confusion of customs and tenure, such features as the overlapping of the hide and the carucate, the simultaneous use of such terms as wapentake, shire, and hundred, and the incidence of thegnage, drengage, and cornage tenure side by side, are eloquent.[42]

The greatest landowner was Uhtraed, Uchtred in Domeday Book, whose name is clearly reminiscent of the Northumbrian lords of Bamburgh. In 1887, Andrew Gray in a highly entertaining essay called ‘The Domesday Record of the Land Between Ribble and Mersey’ wrote:

We would gladly identify him, if we could, with one of the Uhtreds of the great House of Eadwulf…. such identification, however, would be mere guesswork.[43]

Nevertheless, Uhtraed or Uchtred does look like a Northumbrian English name. Other clearly English names, whether Mercian or Northumbrian, are Æthelmund, Almaer, Wulfbert, Wynstan and Godgifu (the only named woman). We also find the Scandinavian names Beornwulf, Stenulf, Aski and Ketil. The ethnicity of the remaining names Dot, Lyfing and Teos is less clear. But we find a Dot holding large estates in Cheshire, so he might have been Mercian English too.

Nevertheless, Uhtraed or Uchtred does look like a Northumbrian English name. Other clearly English names, whether Mercian or Northumbrian, are Æthelmund, Almaer, Wulfbert, Wynstan and Godgifu (the only named woman). We also find the Scandinavian names Beornwulf, Stenulf, Aski and Ketil. The ethnicity of the remaining names Dot, Lyfing and Teos is less clear. But we find a Dot holding large estates in Cheshire, so he might have been Mercian English too.

Of course all these people might be called ‘English’ by the time of the Conquest, although the general scholarly consensus is that in the eleventh century the descendants of the Irish-Norse settlers in north-west England still spoke a version of Old Norse, which would, however, have already started to merge with Northumbrian and Mercian English by this time.[44] An older man at the time of the Conquest could easily have had a great great grandfather who had been one of the very first Irish-Norse settlers in Lancashire about a century and a half before.

The Normans arrive in Lancashire

In the five years immediately following the Conquest the new Norman-French king and his newly enriched barons didn’t seem to have given much attention to the region that would become Lancashire. During the winter of 1069 – 1070, when William and his men were committing regional genocide in the so-called the Harrying of the North, it’s quite possible, likely even, that some parts of the Lancashire Pennines and the region north of the River Ribble called Amounderness (including Preston) were wasted too. In Domesday, of the 59 vills listed under Preston only 19 were said to been ‘inhabited by a few people.., the rest is waste’. But there is no evidence that the ‘ravening wolves’ ever wasted the land between the Ribble and Mersey, and certainly not West Derby Hundred. It had, as Farrer said, escaped ‘the fire and sword of the Conqueror, laying waste the neighbouring shires’.[45]

I have discussed the Harrying of the North elsewhere.[46] William’s men ‘spread out… over more than a hundred miles of territory, slaying many men and destroying the liars of others’.[47] Suffice it to add here, to use just a few more words of the Anglo-Norman historian Orderic Vitalis:

In his (William’s) anger, he commanded that all crops and herds, chattels and food of every kind should be brought together and burned to ashes with consuming fire so that the whole region north of the Humber might be stripped of all means of sustenance…. As a consequence, so serious a scarcity was felt in England, and so terrible a famine fell upon the humble and defenceless people, that more than 100,000 Christian folk of both sexes, young and old alike, perished of hunger.

The Harrying of the North

Following the Harrying of the North and the rebellion of Eadric the Wild in the Welsh borderlands, and the defeat of earl Eadwin, William granted a huge marcher territory and earldom to Hugh d’Avranches, based on Chester – Cheshire. After cowing and dispossessing the local English population and granting most of the county to his men, Earl Hugh spent much of his time slaughtering the Welsh. Orderic wrote: ‘He went about surrounded by an army instead of a household … and ‘wrought great slaughter among the Welsh.’[48]

Majorie Chibnall said in ‘The World of Orderic Vitalis’:[49]

Ruthlessness and insensitivity were qualities necessary for beating down the resolute defence of the princes of North Wales, and Earl Hugh had them in abundance. His huge household had the character of an army, only half held in control. He himself was a great mountain of a man, given over to feasting, hunting, and sexual lust; always in the forefront in battle, and lavish to the point of prodigality.

Slightly further south William granted the earldom of Shrewsbury (Shropshire) to Roger de Montgomerie in about 1071.[50] Like Earl Hugh in Cheshire, Roger quickly divided up the county between his armed knights and household and created powerful border warlords such as Corbet (followed by his sons Roger and Robert), Reinaud de Bailleul-en-Gouffern (who had succeeded Warin ‘the Bald’) and Picot de Sai. As Roger’s biographer John Mason has said, by 1086 ‘of 230 hides held by the earl in the Shropshire border hundreds, 196 were held by these three vassals, whose descendants or representatives were dominant in western Shropshire for some centuries’.[51]

The Norman homeland of Roger de Montgomerie and his son Roger de Poitou

When Roger had first come to England the year after the Battle of Hastings he had left behind his wife Mabel de Bellême (William the Conqueror’s daughter), a woman who, evidently, was ‘violent and aggressive’ and certainly brutally vindictive.[52] He left various sons and daughters behind too, including his eldest son, the ‘notoriously savage’ Robert de Bellême, who would inherit his mothers vast Bellême estates and took the side of William the Conqueror’s oldest son Robert ‘Curthose’ in his revolt against the king in 1077. Second son Hugues (Hugh) de Montgomerie would follow his father as the second earl of Shrewsbury on his father’s death in 1094. But, as we will see, probably sometime in the early 1080s Roger’s third son, also called Roger, who I will refer by his later name of Roger de Poitou (after he married Almodis, daughter of count Aldebert II of La Marche in Poitou, sometime before 1086 ), probably persuaded his father to ask the king to grant him his own territories. King William certainly agreed and gave Roger all the land between the Ribble and Mersey, as well as the wasted lands north of the Ribble called Amounderness, i.e. all of Lancashire, plus vast estates elsewhere in Hampshire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Essex, and Suffolk. According to Orderic:

The prudent old earl obtained earldoms for his two remaining sons, Roger and Arnulph, who, after his death, lost them both for their treasonable practices in the reign of King Henry.

Painting of Roger de Poitou as he might have looked when older back in France

Domesday Book of 1086 is the first time we here about him and Lancashire. It is said that he used to hold it all. But by 1086 Roger had already been stripped of Lancashire and his other holdings. Before I discuss what had possibly happened, let’s ask when Roger had first come to Lancashire? Nothing is certain but let’s start with his likely date of birth. Roger’s father, Roger de Montgomerie, had married Duke William’s daughter Mabel de Bellême in about 1050.[53] They had five surviving sons, Roger de Poitou was the third -a first Roger died young before about 1060-1062. They also had four daughters. John Mason writes:

Orderic’s list of four daughters of Roger and Mabel follows that of their brothers, in an order which is probably that of their birth: Emma (d. 1113), a nun at and later (perhaps as early as c.1074, when she was probably in her early twenties) abbess of her father’s foundation at Alménêches; Matilda (d. 1082×4), who married before 1066 the Conqueror’s half-brother Robert de Mortain; Mabel, who married Hugues de Châteauneuf-en-Thymerais; and Sybil, who married Robert fitz Hamon from south Wales.[54]

Given that at least Emma and Matilda were probably born in the 1050s, this led Mason, among others, to suggest that Roger was born in the mid 1060s. Others, less convincingly, give his date of birth as 1058. The point of this is that if Mason is at all right about Roger’s date of birth then he would have been only about 21 or 22 in 1086, by which time he had been granted all of Lancashire by King William, established his men-at-arms in the manors there, started to build Penwortham castle on the River Ribble and then forfeited his lands for some reason. I can’t help but concurring entirely with John Mason:

The Domesday entries for his (Roger’s) large honour present problems. In five counties (Hampshire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Essex, and Suffolk) he is entered as a normal tenant-in-chief; but in four others (the land between the Ribble and the Mersey, Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and Norfolk) his tenure is entered as a thing of the past: thus at the end of his Derbyshire fee is a note that Roger used to hold the lands, but they are now in the hand of the king. This and other entries suggest that Roger’s lands were all ordered to be taken into the king’s hand late in 1086, but that in some cases the order was not known locally in time to be recorded in Domesday, or recorded in full. In view of his age, Roger cannot have held this honour for long; why he should so soon have lost it, at a time when as far as is known he and his father were loyal to the Conqueror, is not stated.[55]

I would particularly stress the view that Roger ‘cannot have held this honour for long’ and that he had probably only recently forfeited his estates when Domesday was taken in 1086. Roger would be regranted these lands in 1088 by William’s son William Rufus, only to lose them finally again in 1102 after he had joined his eldest brother’s rebellion against King Henry. ‘In consequence he was expelled from England, which he visited again only in 1109. The rest of his life was spent in the politics of La Marche.’[56] But these later French family feuds will not concern us here.

So when Roger arrived in Lancashire in the early 1080s with his men-at-arms and household, no doubt given to him by his father, he would have still been a youth. Knowing how the Norman-French tended to move around in heavily armed, armoured and mounted groups – to protect themselves from attacks by the resentful English and to engage in a little rape and pillage[57] – we can perhaps imagine the scene as they arrived in West Derby, previously the caput of King Edward.

Norman knights

Leading his mounted troops and armed household into the manor of West Derby, Roger was probably full of youthful swagger and scorn for these strange Englishmen with their even stranger language. Ensconcing themselves in the best houses that West Derby had to offer, having no doubt summarily ejected whatever English thegns or other English tenants they found there. And, if they were true Norman warriors, after having first feasted, drunk and maybe whored a bit, Roger and his men would have started to set about finding out what spoils they had been given by right of the conquerors.

Roger was probably helped in this by all his more important men-at-arms. As mentioned, in West Derby Hundred most of the farms (or manors as the French now called them) were in and around present Liverpool, with just a few more up the coast to the north, in places such as Ainsdale, Formby, North Meols, Scarisbrick, Halsall and Skelmersdale. It wouldn’t have taken Roger and his men long to survey the hundred and even to travel to the other five more sparsely settled hundreds in the land between the Ribble and Mersey, or even across the Ribble to Amounderness. When they arrived at each farmstead they would have been met by the fearful pre-Conquest English thegns and some of the farm workers, probably including the formerly powerful Uhtraed if he were still alive. In short order Roger would have doled out (or sub-infeudated to use the legal French term) manor after manor to his men-at-arms and other members of his personal household, telling the resident English in no uncertain terms that they were their new masters and that they had better put up or shut up. By this time the English knew that there was no point in resistance. All they could expect from that was death. Either they would have to accept becoming the Frenchmen’s serfs or they would have to flee and find exile abroad.

Although this is just imagination, from all we know of the Norman colonization of England it probably gets pretty near the truth. Chris Lewis of King College put it this way:

We should probably imagine the point of transition on the ground as the hour when the new landowner turned up at a house and declared, ‘This is mine now, the king has given it to me and the shire court has acknowledged it. I’m going to live here now, Bring me my dinner.’Or,perhaps, ‘The king has given me your land. I’ll be living somewhere else, and you can still live here, but you’ll have to pay me rent from today.’ [57b]

Roger of Poitou’s men

Domesday Book tells us this about what Roger’s men got in West Derby:

These men now hold land of this manor (i.e. West Derby Hundred) by gift of Roger de Poitou: Geoffrey 2 hides and a half carucate, Roger 1 ½ hides, William 1 ½ hides, Warin half a hide, Geoffrey 1 hide, Theobald 1 ½ hides, Robert 2 carucates of land, Gilbert 1 carucate of land.

Their woodland (is) 3 ½ leagues long and 1 ½ leagues and 40 perches broad, and there are 3 eyries of hawks. The whole is worth £8 12s. In each hide are 6 carucates of land.

The desmesne of this manor which Roger held is worth £8. There are in desmesne 3 ploughs and six oxmen, and 1 radman and 7 villans.

Some of these men were given land in the other five hundreds as well, where there are also a few other Frenchmen named.

A Norman manor house

From all the entries in West Derby and the other Lancashire hundreds we can, if we try, get a reasonably good idea of which manors these eight Frenchmen got. We can also try to identify some of them. But these matters would lead us outside the scope of this article. For those interested in these things I would suggest consulting William Farrer’s work and deductions in the ‘Victoria County History of Lancashire’.

But how much land had these eight been given in West Derby? In total they held 48 hides and 3½ carucates. As stated in Domesday Book, one hide in Lancashire was equal to six ploughlands (carucates), so all told these seven men received 51.5 ploughlands, which equates to 57% of the 89 ploughlands (excluding the caput of West Derby held pre-Conquest by King Edward, then by Roger de Poitou and by 1086 by King William) listed for before the Conquest. All the rest of the land in West Derby Hundred had been held by Roger of Poitou and was now held by King William. Very soon most of this royal land would revert to Roger of Poitou and then into the hands of more Frenchmen.

Regarding the other five hundreds in Lancashire south of the Ribble, I won’t here present any statistical analysis, but Domesday says that in all six hundreds in 1086 there were in 188 manors ‘less one’ in which there are 80 hides (480 ploughlands) of arable land. If we subtract the manors and hides in West Derby (60 and 18.8) we get 127 manors and 61.2 hides for the other five hundreds. But I think without a full analysis I won’t look further at these ‘remote’ districts, interesting though they are. But we can say that although in these unattractive areas there were more English left on their barren land than in West Derby, the most attractive land everywhere had already be given to Roger’s followers.

Roger’s first forfeiture

We don’t know how long all this land-grab took, and there was certainly still much more to do by 1086. But given that Roger had for some reason been stripped of his land not long before 1086, and that he had probably arrived in Lancashire only in the first years of the 1080s, it can’t have taken very long. For what reason had Roger’s lands been taken from him prior to 1086?

Earlier historians tended to date Roger forfeiture to 1077 and link it with the first quarrels of William the Conqueror with his son Robert Curthose, but given Roger’s probable age this can’t have been the case. Others have suggested that Roger had made a ‘voluntary surrender or exchange of these estates’.[58] I find this unlikely, but, as John Mason said, why Roger should have lost his rich spoils ‘at a time when as far as is known he and his father were loyal to the Conqueror, is not stated’, and ultimately unknown.

Robert Curthose, rebellious son of William the Conqueror

Lancashire after 1086

It is outside the scope of this essay to look further into the history of the Norman-French take-over and colonization of Lancashire after the Domesday survey. I have restricted our view to events leading up to 1086 and particularly to events in the important hundred of West Derby. Domesday also tells us much about tax and the customary dues of the tenants of the new lords. But this too I will leave to one side for the time being.

Although, evidently, the people of the land between the Ribble and the Mersey hadn’t suffered the slaughter and starvation meted out elsewhere in northern England, they certainly were invaded and colonized, and were set to suffer the ‘oppressions from the proud lords’ and ‘groan under the Norman yoke’ for centuries to come. While I admire the work of William Farrer, I think he erred when he wrote about Lancashire: ‘Very many of the descendants of the Saxon and Danish thanes living at the Conquest possessed their ancestral estates for generations after the Conquest, and if others fell to the position of villeins, they really underwent no great change of status.’[59] In fact there is hardly any evidence at all that the pre-Conquest ‘Saxon and Danish’ thegns ‘possessed their ancestral estates for generations after the Conquest’.

‘Normanist’ historians such as R. Allen Brown could still suggest in recent times say that the Norman take-over of England was not only relatively restrained and civilized but also beneficial to England, as it gave ‘a new lease of life in focusing its attention on Continental Europe’. This I’m afraid is blatant nonsense and flies in the face of all the available evidence, including the evidence presented by Brown himself. But that’s a matter for another time.

The words of the twelfth-century English historian Henry of Huntingdon are certainly applicable to Lancashire:

In King William’s twenty-first year (1087) there was scarcely a noble of English descent in England, but all had been reduced to servitude and lamentation.[60]

Perhaps we should leave the last word with Orderic. Remember this was a man born in Shropshire whose father was a loyal clerical servant of Roger de Montgomery, one of Duke William’s most powerful followers and one of the most powerful men in post-Conquest England. He was also a man who went to Normandy in 1085 to become a monk at the Norman monastery of St. Evroult, and knew many of the Normans involved in the Conquest and their sons.

Perhaps we should leave the last word with Orderic. Remember this was a man born in Shropshire whose father was a loyal clerical servant of Roger de Montgomery, one of Duke William’s most powerful followers and one of the most powerful men in post-Conquest England. He was also a man who went to Normandy in 1085 to become a monk at the Norman monastery of St. Evroult, and knew many of the Normans involved in the Conquest and their sons.

They (the Normans) arrogantly abused their authority and mercilessly slaughtered the native people, like the scourge of God smiting them for their sin… Noble maidens were exposed to the insults of the low-born soldiers and lamented their dishonouring (i.e. rape) by the scum of the earth… Ignorant parasites, made almost mad with pride, they were astonished that such great power had come to them and imagined that they were a law unto themselves. Oh fools and sinners! Why did they not ponder contritely in their hearts that they had conquered not by their own strength but by the will of almighty God, and had subdued a people that was greater and more wealthy than they were, with a longer history?

It is rather ironic that the descendants of a group of Scandinavian Vikings, a people whose leader Rollo had once reputedly told the French king that they were Norsemen and would bend their knee to no man,[61] who would now (though by now thoroughly drenched in French culture and feudal attitudes) make a whole nation bend their knees to them for centuries to come.

In ‘The Rights of Man’ the great English and American radical Thomas Paine said:

If the succession runs in the line of the conqueror the nation runs in the line of being conquered and ought to rescue itself.

And here’s a nice rhyme:

When all England is alofte

Hale are they that are in Christis Crofte;

And where should Christis Crofte be

But between Ribble and Mersey.[62]

The Norseman ‘Rollo’, founder of Normandy and direct ancestor of William the Conqueror

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BAINES, Edward, History of the county palatine and duchy of Lancaster (1836)

BLAND. E, Annals of Southport and District: A Chronological History of North Meols from Alfred the Great to Edward VII (Southport, 2003)

CHANDLER, Victoria, ‘The Last of the Montgomerys: Roger the Poitevin and Arnulf’ in Historical Research 62 (147) (1989)

CHIBNALL, Marjorie, The World of Orderic Vitalis (Oxford, 1984)

CHIBNALL, Marjorie, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, 6 vols., (Oxford, 1969—1980)

CLARKSON, Tim, The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland (Edinburgh, 2010)

DOWNHAM, Claire, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland. The Dynasty of Ivarr to A.D. 1014 (Edinburgh, 2007)

EKWALL, Eilert, Scandinavian and Celts in the North-West of England (Lund, 1918)

EKWALL, Eilert, Place-names of Lancashire (Manchester, 1922)

FARRER, William, ‘Introduction to the Lancashire Domesday’ in The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster, vols. 1&3.

FARRER, William, ‘Notes on the Domesday Survey of the land between Ribble and Mersey’ in Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, vol. 16, pp. 1-38 (1899)

FARRER, William, A History of the Parish of North Meols (Liverpool, 1903)

FARRER William & BROWNBILL, J, eds., The Victoria History of the Lancaster, 8 vols., (London, 1906-1914)

FERGUSON, Robert, The Northmen of Cumberland and Westmorland (London, 1856)

FLEMING, Robin, Kings and Lords in Conquest England (Cambridge, 1991)

FOOT, Sarah, Æthelstan: the first king of England. (Yale, 2011)

FORESTER, Thomas, ed. and trans., The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester with the two Continuations (London, 1854)

FORESTER, Thomas, trans., The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy by Orderic Vitalis (OV), 4 vols., (London, 1853-4)

GRAHAM-CAMPBELL, James, ‘The Northern Hoards’, in Edward the Elder, 899-924, edited by N. J. Higham and D. H. Hill (London, 2011),

GRAHAM-CAMPBELL, James, Viking Treasure from the North-West, the Cuerdale Hoard in its Context, National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside (Liverpool, 1992)

GRAY, Andrew E. P., ‘The Domesday Record of the Lands between Ribble amd Mersey’, in The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol 39, pp. 35-48 (Liverpool, 1887)

GREGSON, Matthew, ‘Domesday Book’ in Portfolio, Second Edition, with Additions, of Fragments, Relative to the History and Antiquities of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster, pp. 42 – 48 (1824)

GEENWAY, D., ed. and trans., Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000 – 1154 (Oxford, 2002)

GRIFFITHS, David, Vikings of the Irish Sea: Conflict and Assimilation A.D. 790-1050 (Stroud, 2010)

HIGHAM, Nick, ‘The Scandinavians in North Cumbria: Raids and Settlements in the Later Ninth to Mid Tenth Centuries’, in The Scandinavians in Cumbria, edited by John R. Baldwin and Ian D. Whyte, Scottish Society for Northern Studies 3 (Edinburgh, 1985

HIGHAM, N. J., Edward the Elder, 899–924, (London, 2001)

HIGHAM, Nicholas, ‘The Viking-Age Settlement in the North-Western Countryside: Lifting the Veil?’ in Land, Sea and Home: proceedings of a Conference on Viking-Period Settlement, at Cardiff, July 2001, edited by John Hines et al. (Leeds, 2004)

HIGHAM, Nicholas, ‘The Northern Counties to AD 1000’ in the Regional History of England Series (1986)

HIGHAM, Nicholas, The Norman Conquest (1998)

HIGHAM, Nicholas, The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350-1100 (1993)

HOLT, James Clarke, Colonial England, 1066–1215 (London, 1997)

JESCH, Judith, ‘Scandinavian Wirral’ in Wirral and its Viking Heritage, edited by Paul Cavill et al (Nottingham, 2000)

KAPELLE, William, The Norman Conquest of the North (London 1979)

KENYON, Denise, The Origins of Lancashire (Manchester, 1991)

LEWIS, C. P. Lewis, ‘The Invention of the Manor in Norman England’ in Anglo-Norman Studies 24, Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2011, ed., David Bates (Woodbridge, 2012)

LEWIS, C. P. Lewis, ‘The king and Eye: a study in Anglo-Norman politics’ in English Historical Review 104 (1989)

LEWIS, C. P. Lewis, ‘The early earls of Norman England’ in Anglo-Norman Studies, 13 (1990)

LEWIS, Stephen M., Exile rather than servitude – the English leave for Constantinople (Bayonne, 2013)

LEWIS, Stephen M., On Writing History (Bayonne, 2013)

LEWIS, Stephen M., The first Scandinavian settlers in North West England (Bayonne, 2014)

LEWIS, Stephen M., North Meols and the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire (Bayonne, 2014)

LEWIS, Stephen M., Forne Sigulfson – the ‘first lord of Greystoke in Cumbria (Bayonne, 2013)

LIVINGSTON, Michael, ed., The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook (Exeter, 2011)

MASON, J. F. A., ‘Montgomery, Roger de, first earl of Shrewsbury (d. 1094)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford, 2004)

MASON, J. F. A., ‘Roger de Montgomery and His Sons (1067–1102)’ in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th series vol. 13 (1963)

MASON, J. F. A., ‘The officers and clerks of the Norman earls of Shropshire’ in Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society, 56 (1957–60)

MONTGOMERY, T. H., A genealogical history of the family of Montgomery including the Montgomery Pedigree (Philadelphia, 1868)

MORRIS, Marc, The Norman Conquest (London, 2013)

REX, Peter, The English Resistance – The Underground War Against the Normans, (Stroud, 2004)

REX, Peter, 1066 – A New History of the Norman Conquest (Stroud, 2011)

SAWYER, P. H., ‘Wulfric Spot (d. 1002×4)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004)

SCHOFIELD, R., ‘Roger of Poitou’ in Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol, 117, pp. 185 – 98 (Liverpool, 1965)

SHARPE, Richard, Norman Rule in Cumbria 1092-1136 (Kendal, 2006)

STEENSTRUP, Johannes, Normannerne, Vol 1 (Copenhagen, 1876) STENTON, Frank, Anglo Saxon England (Oxford, 1970)

STORM, Gustav, Kritiske Bidrag til Vikingetidens Historie (Oslo, 1878)

THOMPSON, Kathleen (1991). ‘Robert de Bellême Reconsidered’ in Anglo-Norman Studies. Vol. 13, Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1990, edited by Marjorie Chibnall (Woodbridge, 1991)

THOMPSON, Kathleen, ‘Bellême, Robert de, earl of Shrewsbury and count of Ponthieu (bap. c.1057, d. in or after 1130)’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004)

THORPE, Benjamin, ed. and trans., The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle According to the Several Original Authorities, Vol 2, (London, 1861)

VOGEL, Walther, Die Normannen und das Frankische Reich bis zur Grundung der Normandie (799-911) (Heidelberg, 1906)

WAINWRIGHT, F. T., Scandinavian England: Collected Papers (Chichester, 1975)

WAINWRIGHT, F. T, ‘The Anglian settlement of Lancashire’ in The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol 19 (1941)

WHITELOCK, Dorothy, ed., English Historical Documents, Vol 1, AD 500-1042 (London, 1955)

WILLIAMS, Ann & MARTIN, G. H., eds., Domesday Book – A Complete Translation (DB) 2nd edition (London, 2002)

WORSAAE, J. J. A., An Account of the Danes and Norwegians in England, Scotland, and Ireland (London, 1852)

WOOLF, Alex, From Pictland to Alba 789-1070 (Edinburgh, 2007)

NOTES AND REFERENCES

[1] Kapelle, The Norman Conquest of the North, p. 231

[2] Orderic Vitalis, quoted in Fleming, Kings and Lords, p. 107

[3] Greenway, Henry of Huntingdon, p. 31

[4] See Fleming, Kings and Lords, p. 205

[5] All quotes from the works of Orderic Vitalis can be found either in Chibnall, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis , or Forester, The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy by Orderic Vitalis

[6] See Lewis, The Normans come to Cumbria and Kapelle, The Norman Conquest of the North

[7] Morris, The Norman Conquest, p. 352

[8] See Fleming, Kings and Lords for a full analysis of this divvying up.

[9] See Morris, The Norman Conquest and Rex, The English Resistance

[10] Fleming, Kings and Lords,

[11] Morris, The Norman Conquest, p. 287

[12] Fleming, Kings and Lords, pp. 108-109

[13] See Morris The Norman Conquest for a discussion on the reasons for Domesday survey

[14] See Kapelle The Norman Conquest of the North, Morris, The Norman Conquest

[15] See Rex, The English Resistance, Morris, The Norman Conquest

[16] See Lewis, Exile rather than servitude

[17] Morris, The Norman Conquest, pp.320-321

[18] Lewis, Forne Sigulfson- the ‘first’ lord of Greystoke in Cumbria

[19] Farrer, Introduction to the Lancashire Domesday

[20] Sawyer, Wulfic Spot

[21] See Higham, The Kingdom of Northumbria ; Kapelle, The Norman Conquest of the North; Clarkson, The Men of the North

[22] For example see articles in Wainwright, Scandinavian England

[23] See Clarkson, The Men of the North

[24] Downham, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland; Woolf, From Pictland to Alba; Livingston, The Battle of Brunaburh, Wainwright, Scandinavian England

[25] See references to their work in the Bibliography

[26] Wainwright, ‘The Scandinavians in Lancashire’ in Scandinavian England, p. 226

[27] See discussions in Wainwright, ‘The Scandinavians in Lancashire’ in Scandinavian England

[28] Wainwright, ‘The Scandinavians in Lancashire’ in Scandinavian England, p. 184, gives other examples

[29] Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (ASC) in Whitelock, English Historical Documents; Clarkson, The Men of the North; Higham, Edward the Elder; Downham, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland

[30] See articles on Amounderness in Wainwright, Scandinavian England and Farrer, The Victoria County History of Lancashire, vol. 3

[31] See Foot, Æthelstan: the first king of England; Livingston, The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook

[32] See Morris, The Norman Conquest; Fleming, Kings and Lords; Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England

[33] Fleming, Kings and Lords, pp. 22-103

[34] See Wainwright, ‘The Scandinavians in Lancashire’ in Scandinavian England

[35] Farrer, Notes on the Domesday Survey

[36] Some of this interpretation is debatable.

[37] Gray, The Domesday Record

[38] Throughout I will use Ann Morris’s edition of Domesday Book – A Complete Translation, second edition 2002, including her ‘translated’ spellings of names. Unless otherwise stated any reference to an entry in DB will be to this edition.

[39] Farrer, Introduction to the Lancashire Domesday

[40] Probably Hale, Garston, Liverpool, Everton, Crosby and perhaps Thingwall and Aintree.

[41] These are not stated but likely were:

[42] Farrer, Notes on the Domesday Survey

[43] Gray, The Domesday Record

[44] See discussion and references in Wainwright, Scandinavian England.

[45] Farrer, Notes on the Domesday Survey

[46] See Lewis, The Normans Come to Cumbria.

[47] Morris, The Norman Conquest , p. 229

[48] Quotede in Morris, The Norman Conquest, p. 292

[49] Chibnall, The World of Orderic Vitalis, p. 15

[50] Other dates have been suggested, see C. P. Lewis, the king and Eye for example

[51] Mason, Montgomery, Roger de, first earl of Shrewsbury

[52] Thompson, Bellême

[53] Mason, Montgomery, Roger de, first earl of Shrewsbury

[54] Mason, Montgomery, Roger de, first earl of Shrewsbury

[55] Mason, Montgomery, Roger de, first earl of Shrewsbury

[56] Mason, Montgomery, Roger de, first earl of Shrewsbury

[57] There is ample evidence in Orderic Vitalis and elsewhere that the Normans were wont to rape and pillage

[57b] Lewis, ‘The Invention of the Manor’, p. 147

[58] Farrer, Introduction to the Lancashire Domesday

[59] Farrer, Notes on the Domesday Survey

[60] Greenway, Henry of Huntingdon, p.31

[61] See Vogel, Die Normannen und das Frankische Reich

[62] Harland & Wilkinson, Lancashire Legends, p.184

In North Meols and along the nearby River Ribble and its tributary the River Douglas the Vikings would have found many convenient places to ground their ships. As suggested, the area was either not inhabited or only sparsely so. In the records we find not one mention of any confrontation between these Scandinavians and any resident peoples. This implies that the settlement was fairly peaceable. The great historian of English place names, Eilert Ekwall, suggested that this is ‘only a hypothesis’ because it is an argument ‘from silence’, meaning that this view comes only from the fact that there are no written records of clashes between Scandinavian settlers and native inhabitants.[13] Frederick Wainwright, by far the greatest historian of the Scandinavian settlement of north-west England, wrote that the evidence for the peaceable nature of the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire ‘is none the less powerful… since it is almost inconceivable that an organized military conquest or a violent social upheaval, even in the remote north-west, should altogether escape the notice of both contemporary and later annalists’. Wainwright added:

In North Meols and along the nearby River Ribble and its tributary the River Douglas the Vikings would have found many convenient places to ground their ships. As suggested, the area was either not inhabited or only sparsely so. In the records we find not one mention of any confrontation between these Scandinavians and any resident peoples. This implies that the settlement was fairly peaceable. The great historian of English place names, Eilert Ekwall, suggested that this is ‘only a hypothesis’ because it is an argument ‘from silence’, meaning that this view comes only from the fact that there are no written records of clashes between Scandinavian settlers and native inhabitants.[13] Frederick Wainwright, by far the greatest historian of the Scandinavian settlement of north-west England, wrote that the evidence for the peaceable nature of the Scandinavian settlement of Lancashire ‘is none the less powerful… since it is almost inconceivable that an organized military conquest or a violent social upheaval, even in the remote north-west, should altogether escape the notice of both contemporary and later annalists’. Wainwright added: As in Cumbria further north, between the Mersey and the Ribble we find Scandinavian place names everywhere. In the immediate vicinity of North Meols itself we find Crossens, Birkdale, Ainsdale, Formby, Altcar, Crosby, Litherland and Kirkdale. Inland we find Scarisbrick, Tarlscough, Tarleton, Ormskirk, Kellamerg and Hesketh. These are all Norse names. The same is true up and down the coast.[15] If we were to add in lesser names of fields and topographical features the list would be almost endless.

As in Cumbria further north, between the Mersey and the Ribble we find Scandinavian place names everywhere. In the immediate vicinity of North Meols itself we find Crossens, Birkdale, Ainsdale, Formby, Altcar, Crosby, Litherland and Kirkdale. Inland we find Scarisbrick, Tarlscough, Tarleton, Ormskirk, Kellamerg and Hesketh. These are all Norse names. The same is true up and down the coast.[15] If we were to add in lesser names of fields and topographical features the list would be almost endless.

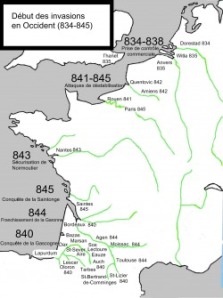

There is a story which may or may not be true telling how the Vikings had managed to take the city of Nantes so easily. Lietaud, a tenth-century monk of St. Mesmin wrote about Nantes in his Miracles of St. Martin of Vertou. Using Ferdinand Lot’s summary:

There is a story which may or may not be true telling how the Vikings had managed to take the city of Nantes so easily. Lietaud, a tenth-century monk of St. Mesmin wrote about Nantes in his Miracles of St. Martin of Vertou. Using Ferdinand Lot’s summary: Which roughly translates as follows: ‘The first severe persecution of the Northmen was by the wicked and sacrilegious Hasting, whose predatory violence raged for more than thirty years from year of our Lord 836… ‘ The cathedral of Coutances had been destroyed by Hastein/Hasting in 836, eight years before we find him at the walls of Toulouse.

Which roughly translates as follows: ‘The first severe persecution of the Northmen was by the wicked and sacrilegious Hasting, whose predatory violence raged for more than thirty years from year of our Lord 836… ‘ The cathedral of Coutances had been destroyed by Hastein/Hasting in 836, eight years before we find him at the walls of Toulouse.

The eyewitness account of 843 contained in the Annals of Angers calls them ‘ferocious Northmen’, while the Chronicle of Nantes itself calls them ‘Northmen and Danes’. The Annals of Fontanelle, written in the Abbey of Fontanelle which Asgeir had plundered on his raid up the Seine in 841, simply says that, ‘in A.D. 841 the Northmen arrived on the twelfth of May with their chief, Asgeir’. It should also be noted that Norway was not yet a definite ‘country’. The province of Vestfold was for a long time claimed as, and de facto was, a part of the realm of the kings of Denmark. In 813 the Frankish Royal Chronicles report that, ‘The kings (of Denmark) were not at home but had marched with an army towards Westarfalda, an area in the extreme northwest of their kingdom’.

The eyewitness account of 843 contained in the Annals of Angers calls them ‘ferocious Northmen’, while the Chronicle of Nantes itself calls them ‘Northmen and Danes’. The Annals of Fontanelle, written in the Abbey of Fontanelle which Asgeir had plundered on his raid up the Seine in 841, simply says that, ‘in A.D. 841 the Northmen arrived on the twelfth of May with their chief, Asgeir’. It should also be noted that Norway was not yet a definite ‘country’. The province of Vestfold was for a long time claimed as, and de facto was, a part of the realm of the kings of Denmark. In 813 the Frankish Royal Chronicles report that, ‘The kings (of Denmark) were not at home but had marched with an army towards Westarfalda, an area in the extreme northwest of their kingdom’. The eyewitness account in the Annals of Angers says the following:

The eyewitness account in the Annals of Angers says the following:

Being an eloquent plotter of evil deeds, Lambert had persuaded the Vikings to put to sea and he led then safely round the coasts of ‘new’ Brittany and up the River Loire to the city of Nantes. The city soon fell because it was defenceless; those who should have been defending it were all dead. We then hear that while the Vikings were ‘greedily’ ravaging and plundering the city Lambert told them of a church full of gold and silver on the island of ‘Bas’ (Batz, behind St. Nazaire). So the Vikings gathered together all their ships and, led by Lambert who showed them the way, they rowed through the bays and coves of Brittany to Bas.

Being an eloquent plotter of evil deeds, Lambert had persuaded the Vikings to put to sea and he led then safely round the coasts of ‘new’ Brittany and up the River Loire to the city of Nantes. The city soon fell because it was defenceless; those who should have been defending it were all dead. We then hear that while the Vikings were ‘greedily’ ravaging and plundering the city Lambert told them of a church full of gold and silver on the island of ‘Bas’ (Batz, behind St. Nazaire). So the Vikings gathered together all their ships and, led by Lambert who showed them the way, they rowed through the bays and coves of Brittany to Bas.