‘Et Strat Clut vastata est a Saxonibus’ (And Strathclyde was devastated by the Saxons) – Welsh Annales AD 946.

‘This year King Edmund ravaged all Cumberland, and granted it to Malcolm, king of the Scots, on the condition that he should be his fellow-worker as well by sea as by land.’ – Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for AD 945.

‘How king Eadmund gave Cumberland to the king of the Scots.’ – A.D. 946. ‘Agapetus sat in the Roman chair ten years, six months, and ten days. In the same year king Eadmund, with the aid of Leoling, king of South Wales, ravaged the whole of Cumberland, and put out the eyes of the two sons of Dummail, king of that province. He then granted that kingdom to Malcolm, king of the Scots, to hold of himself, with a view to defend the northern parts of England from hostile incursions by sea and land.’ – Roger of Wendover, Flowers of History, circa 1235.

King Edmund

In the year 945/6 a British king of Cumbria (the kingdom of the Strathclyde Britons) called ‘Dunmail’ was probably defeated in battle by the West-Saxon English king Edmund. The event has become legendary. A small kernel of historical truth has been embellished over the centuries to make of King Dunmail a veritable King Arthur or an Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, an heroic figure who lies sleeping, to be called upon one day to return and save his people in their hour of need. I will discuss the historical facts and setting in a forthcoming article. Dunmail was probably Cumbrian King Dyfnmal ap Owain (Donald son of Owen), and he certainly wasn’t the ‘last king’ of the Cumbrians. But here I’d simply like to draw together just a few of the myriad versions of the legend.

Let’s begin with William Wordsworth. In his 1805 poem The Waggoner he wrote:

Meanwhile, uncertain what to do,

And oftentimes compelled to halt,

The horses cautiously pursue

Their way, without mishap or fault;

And now have reached that pile of stones,

Heaped over brave King Dunmail’s bones;

His who had once supreme command,

Last king of rocky Cumberland;

His bones, and those of all his Power

Slain here in a disastrous hour!

Countless generations of tourists to the Lake District have been told that this ‘pile of stones’, which can still be seen on Dunmail Raise as it rises south from Thirlmere, marks the spot of the battle and even, in many versions, Dunmail’s burial place.

Although the seeds of the legend of Dunmail find their origins in the comments of Roger of Wendover in the early thirteenth century quoted above, for a long time antiquaries and travel writers stuck to the basic facts and stated the uncertainty of matters. King Charles 1’s surveyor John Ogilby in his The Traveller’s Guide: Or, A Most Exact Description Of The Roads Of England (1699) only said that there was “a great heap of stones called Dunmail-Raise-Stones, supposed to have been cast up by Dunmail K(ing) of Cumberland for the bounds of his kingdom”.

In 1774, in A Tour of Scotland and the Hebrides, Thomas Pennant wrote:

On a high pass between the hills, observe a large Carnedd called Dunmail Wrays stones, collect6ed in memory of a defeat, A.D. 946. given to a petty king of Cumberland, of that name, by Edmund 1. Who with the usual barbarity of the times, put out the eyes of his two sons, and gave the country to Malcolm, king of Scotland, on condition he preserved in peace the northern parts of England.

William Gilpin said in his Observations, relative chiefly to Pictureseque Beauty, Made in the Year 1772, On several Parts of England; particularly the Mountains and Lakes of Cumberland, and Westmoreland (1786):

… we came to the celebrated pass, known by the name Dunmail-Raise, which divides the counties of Cumberland and Westmoreland. The history of this rude monument, which consists of a monstrous pile of stones, heaped on each side of an earthen mound, is little known. It was probably intended to mark a division, not between these two northern counties; but rather between the two kingdoms of Scotland and England, in elder times, when the Scottish border extended beyond its present bounds. And indeed this chain of mountains seem to be a much more natural division of the two kingdoms, in this part, than a little river in champaign country, like the Esk, which now divides them. It is said, this division, was made by a Saxon prince, on the death of Dunmail the last king of Cumberland, who was here slain in battle…

Dunmail Raise

Around the same time, 1784, Thomas West wrote in A guide to the lakes of Cumberland, Westmorland and Lancashire:

… the road ascends to Dunmail-raise, where lie the historical stones, that perpetuate the name and fall of the last king of Cumberland, defeated there by the Saxon monarch Edmund, who put out the eyes of the two sons of his adversary, and; for his confederating with Leolin, King of Wales, against him wasted his Kingdom, and then gave it to Malcolm, King of Scots, who held it in fee of Edmund A.D. 944 or 945. The stones are a heap and have the appearance of a karn, or barrow. The wall that divides the counties is built over them, which proves their priority of time in that form.

It’s only when we get to the Romantic era of Wordsworth and later into the Victorian and Edwardian periods that the legend really starts to take shape. I particularly like John Pagan White’s 1873 poetic rendition in his Country Lays and Legends of the English Lake Country:

KING DUNMAIL.

They buried on the mountain’s side

King Dunmail, where he fought and died.

But mount, and mere, and moor again

Shall see King Dunmail come to reign.Mantled and mailed repose his bones

Twelve cubits deep beneath the stones ;

But many a fathom deeper down

In Grisedale Mere lies Dunmail’s crown.Climb thou the rugged pass, and see

High midst those mighty mountains three,

How in their joint embrace they hold

The Mere that hides his crown of gold.There in that lone and lofty dell

Keeps silent watch the sentinel.

A thousand years his lonely rounds

Have traced unseen that water’s boundsHis challenge shocks the startled waste,

Still answered from the hills with haste,

As passing pilgrims come and go

From heights above or vales below.When waning moons have filled their year,

A stone from out that lonely Mere

Down to the rocky Raise is borne,

By martial shades with spear and horn.As crashes on the pile the stone,

The echoes to the King make known

How still their faithful watch they hold

In Grisedale o’er his crown of gold.And when the Raise has reached its sum,

Again will brave King Dunmail come ;

And all his Warriors marching down

The dell, bear back his golden crown.And Dunmail, mantled, crowned, and mailed,

Again shall Cumbria’s King be hailed ;

And o’er his hills and valleys reign

When Eildon’s heights are field and plain.

Grisedale Tarn

W. T. Palmer’s version of 1908 in The English Lakes is more elaborate, literally more inventive and certainly historically incorrect regarding the English king involved and the identity of the Cumbrians themselves:

The cairn of Dunmail, last king of Pictish (sic) Cumbria slain in battle with Edgar (sic) the Saxon, is here, a formless pile of stones. There is a legend concerning this spot.

The crown of Dunmail was charmed, giving to its wearer a succession in his kingdom. Therefore King Edgar (sic) of the Saxons coveted it above all things. When Dunmail came to the throne of the mountainlands a wizard in Gilsland Forest held a master-charm to defeat the purpose of his crown. He Dunmail slew. The magician was able to make himself invisible save at cock crow, and to destroy him the hero braved a cordon of wild wolves at night. At the first peep of dawn he entered the cave where the wizard was lying. Leaping to his feet the magician called out, “Where river runs north or south with the storm” ere Dunmail’s sword silenced him forever. The story came to the ear of the Saxon, who after much inquiry of his priests found that an incomplete curse, though powerful against Dunmail, could scarcely harm another holder of the crown. Spies were accordingly sent into Cumbria to find where a battle could be fought on land favourable to the magician’s words. On Dunmail raise, in times of storm even in unromantic to-day, the torrent sets north or south in capricious fashion. The spies found the place, found also fell-land chiefs who were persuaded to become secret allies of the Saxon. The campaign began. Dunmail moved his army south to meet the invader, and they joined battle on this pass. For long hours the fight was with the Cumbrians; the Saxons were driven down the hill again and again. As his foremost tribes became exhausted, Dunmail retired and called on his reserves—they were mainly the ones favouring the Southern king. On they came, spreading in well-armed lines from side to side of the hollow way, but instead of opening to let the weary warriors through they delivered an attack on them. Surprised, the army reeled back, and their rear was attacked with redoubled violence by the Saxons. The loyal ranks were forced to stand back-to- back round their king; assailed by superior masses they fell rapidly, and ere long the brave chief was shot down by a traitor of his own bodyguard.

“My crown,” cried he, “bear it away; never let the Saxon flaunt it.”

A few stalwarts took the charmed treasure from his hands, and with a furious onslaught made the attackers give way. Step by step they fought their way up the ghyll of Dunmail’s beck—broke through all resistance on the open fell, and aided by a dense cloud evaded their pursuers. Two hours later the faithful few met by Grisedale tarn, and consigned the crown to its depths — “till Dunmail come again to lead us.”

And every year the warriors come back, draw up the charmed circlet from the depths of the wild mountain tarn, and carry it with them over Seat Sandal to where their king is sleeping his age-long sleep. They knock with his spear on the topmost stone of the cairn, and

from its heart comes a voice, “Not yet; not yet; wait awhile, my warriors.”

In 1937 Arthur Mee wrote in The Lake Counties:

A little south of Wythburn the high road crosses over into Westmorland. Beside it at the top of the pass is a great heap of stones known as Dunmail Raise, with its own little tradition of something that happened on this boundary 1000 years ago. Here, it is thought, the battle took place in which the Saxon king Edmund defeated Dunmail, the last king of Cumbria, whose territory was then handed over to King Malcolm of Scotland.

More recently another writer put it thus:

Dunmail Raise marked the boundary between Cumberland and Westmorland, the name coming from a heap of stones which in folklore marks the burial place of the last King of Cumberland, King Dunmail or, as sometimes spelt, Domhnall. In 945, King Edmund, who ruled almost undisputed over the remainder of England, joined forces with King Malcolm of Scotland in order to defeat the last bastion of Celtic resistance in his kingdom. In his last battle, King Dunmail was killed by Edmund himself. His body was carried away by faithful warriors, and buried under a great pile of stones.

King Edmund is reputed to have captured Dunmail’s two sons and had their eyes put out. The Crown of King Dunmail was thrown into Grisedale Tarn on the Helvellyn range. Legend has it that the crown was enchanted, giving its wearer a magic right to the Kingdom, thus it was important to prevent it from falling into Saxon hands. On victory, Edmund gave Cumberland to King Malcolm of Scotland, and it was only when Canute came to the throne that Cumberland came back under English rule in exchange, 87 years later, for Lothian.

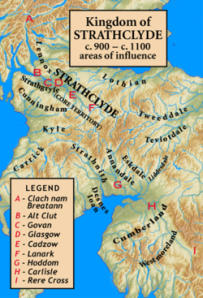

The Kingdom of Cumbria – Strathclyde

In their Ghoulish Horrible Hair raising Cumbrian Tales (1981), Herbert and Mary Jackson add yet more details:

In the aftermath of a ferociously fought battle near Dunmail Raise, just south of Thirlmere reservoir, between King Dunmail of Cumberland and the Saxon army, in the year circa 940 AD, the following legend is written:

After the battle, as King Dunmail lay dying, his last words were. “My crown, bear it away, never let the Saxon flaunt it.”

For it was known that whoever wore the crown of Dunmail would succeed to the Kingdom of Cumbria. The King’s personal body guard removed the crown from the head of their dying monarch and with unprecedented gallantry fought their way through the Saxon lines.

Eventually they reached Grisdale tarn, where with all due ceremony and reverence, the crown was consigned to its deepest waters, with these words, “Till Dunmail come again to lead us.”

Each year, on the anniversary of the King’s death, his warriors return to the tarn. The crown is retrieved and carried back to the cairn of stones under which their beloved Dunmail lies. In turn, the warriors knock with their spears on the topmost stones of the cairn.

From that grave a voice cries out. “Not yet; not yet – wait a while my warriors.” The day is yet to come when the spirit of Dunmail will re-join his warriors and crown a new King of Cumbria.

King Owain, Dunmail’s father, came to the throne in circa 920. A battle took place on the flat of a mountain top at Ecclfechan. What happened to Owain after the battle against the English in which he lost in 938 is not known. But his son went on to succeed him.

Shortly after this, another battle took place as they fought step by step up the Ghyll of Dunmail’s beck – broke through all resistance on the open fell, and, aided by a dense cloud, evaded their pursuers. Two hours later the faithful few met by Grisdale Tarn, and consigned the crown to its depths – “till Dunmail come again to lead us.” And every year the warriors come back, draw up the magic circlet from the depths of the wild mountain tarn, and carry it with them over the Seat Sandal to where the king is sleeping his age long sleep. They knock with his spear on the topmost stone of the cairn and from its heart comes a voice. “Not yet; not yet – wait a while my warriors.”

Cumbrian Flag

It’s all wonderful stuff but there is not a shred of historical evidence for any of it. That a battle was fought in 945/6 between a Cumbrian (Strathclyde British) king and the English king Edmund is quite likely and it’s also quite possible that Edmund was in league at this time with King Malcolm of Alba (Scotland). It’s even possible that the king was the historically attested Cumbrian, King Dyfnwal ap Owain, and even that his two sons had their eyes put out by Edmund – although the earliest mention of this blinding was by the thirteenth-century Roger of Wendover. All the rest is legend, if not purely literary myth, but is a great yarn.

I will show in my forthcoming article that Dunmail/Dyfnwal certainly wasn’t the last king of Cumbria and probably didn’t die in the battle against the English either; facts that haven’t stopped local sub-aqua clubs searching for Dunmail’s crown in Grisedale tarn! I hope they find it.